What markets are really worried about

- Published

It has been a dismal start to the year for global stock markets.

For Wall Street the first week has been described as the worst start ever, external.

In the first two weeks of 2016, Frankfurt and Tokyo fell by double-digit percentages. In New York the fall was 9%, in London 8%.

But the eye of the storm was China, where the main index in Shanghai lost 19% of its value in the same period.

Commodity prices have also tumbled. Crude oil prices fell to below $30 a barrel for the first time in nearly 12 years.

At times share prices have followed oil downwards. That is to be expected for the shares of companies in the oil business, but for others it reduces costs and leaves consumers with more to spend on their products.

So what is going on? Do these financial market developments tell us anything about the state of the global economy?

Global oil prices have also been tumbling

Currency under pressure

The fundamental forces are not new. There is the slowdown in emerging economies' growth. China is the outstanding example, but certainly not the only one.

It was the Chinese market where the instability began, and spread around the world.

In itself, the Chinese stock market is not the fundamental international problem. Yes, it is a serious problem for those Chinese investors who bought shares when prices were high. They have lost a great deal of money.

But there are too few of them for it to have a likely dramatic impact on consumer spending in China. And there are too few foreign investors in the Chinese market for there to be serious losses inflicted outside the country as a direct consequence.

It's not just the stock market. The currency, the yuan, has also been under pressure. It has also lost ground this year, though not on the scale of the stock market. The official, or onshore, rate moved down by nearly 2% in the first week.

It is in part a sign of Chinese savers wanting to get their money out, wondering what sort of return they will get in China. There is also a concern that if they delay the currency will fall further and they will get less for their money.

Some suggest that there is also a possibility of the decline in the yuan turning into a full-blown loss of confidence, external.

Rocky path?

These financial market pressures on China are in part at least a symptom of the wider and much discussed economic slowdown.

Ever since China's economy began to lose some pace, there has been uncertainty about how well the authorities would manage the process.

Certainly China needed to slow to a more sustainable pace. But would the path be a rocky one, with too abrupt a slowdown?

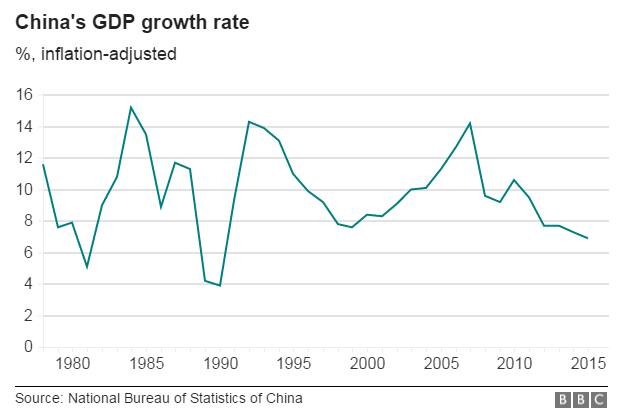

So far, the official figures suggest a significant but not catastrophic slowdown in growth. After three decades of 10% average growth, China slowed to 6.9% last year, according to the official figures just published.

The IMF's new assessment of the economic outlook predicts further easing of the pace to 6.3% this year and 6.0% in 2017.

Certainly these figures are viewed with extreme scepticism by some, but not all. The Economist said last week, external in anticipation of a 2015 figure of close to 7% "that figure may be an overestimate but it is not entirely divorced from reality".

What is clear is that it is substantially slower than it was just five or six years ago.

Shift to services

The new IMF World Economic Outlook, external notes that China has experienced a "faster-than-expected slowdown in imports and exports, in part reflecting weaker investment and manufacturing activity".

China's shift towards services and consumer spending had been widely expected

Now it is true that all those trends are widely seen as necessary, inevitable and even desirable. China's investment levels are very high and could not be sustained.

It has been widely expected that the economy would shift towards services with less emphasis on manufacturing. Service industries mean more emphasis on Chinese consumers, less on exports and less need for imports of industrial raw materials.

The unnerving bit in the IMF comment is the "faster than expected". The market wobbles were not driven by the IMF report - it has only just been published in the past 24 hours. But they are partly about whether the slowdown might be a crash rather than a gentle deceleration.

Beyond China

The jitters about the economic outlook are not just over China. The IMF's new forecast downgrades the outlook for the emerging and developing countries. The ones that stand out are Russia and Brazil.

That's partly about the low prices of oil and other commodities as well as political problems, external for Russia, domestic for Brazil. There's also a hefty downgrade in the forecast for South Africa.

The broad picture from the new IMF forecast is for a modest acceleration in global economic growth this year and a little more in 2017. But there are also risks and they are bothering the markets.

The yuan has been sliding while the dollar had been on the rise in recent months

The uncertainty about China is one. There are also risks from the strong dollar. At bottom the strength of the dollar is down to the fact that the US economy is recovering better than most of the developed nations, which in itself is good news for the US's trade partners - in other words, a lot of countries.

But there is a downside. The US recovery has led to the Federal Reserve's decision to raise interest rates last month and the widely shared expectation that it will take more such steps this year.

These moves will be gradual, but the impact of the upward trend in US interest rates is already apparent. The prospect of higher returns in the US has encouraged investors to sell assets in other countries and buy dollars, pushing the currency higher.

The converse of that is weaker currencies for many emerging economies. The IMF's chief economist, Maurice Obstfeld, said that effect can be a useful shock absorber up to a point. It makes those countries' industries more competitive. But if they have debts in dollars they become more of a burden.

Higher interest rates in the US also mean they are likely to face higher rates themselves. That effect could be magnified if international investors become more wary about what they perceive to be risky assets. Add all those factors together and you could have the potential for a serious debt problem, at least in some countries.

Boom over?

The IMF also warns of a risk of a sudden rise in global risk aversion - essentially investors in the markets becoming sensitive to the risks and shifting towards what are perceived as safe assets such as US government bonds (its debts) and gold. There has been a bit of that going on already in the markets as investors sold shares and commodities, including oil.

Some observers think that many markets were riding for a fall. Asset prices were pumped up by ultra-low interest rates in the developed world and also by the central banks that have engaged in quantitative easing, buying financial assets with newly created money.

That happened with shares, with bonds and with commodities. For commodities the boom is well and truly over, partly due to the slowdown in China and in the case of oil mainly due to plentiful supplies.

Clearly there are some troublesome developments and the IMF has a warning: "If these key challenges are not successfully managed, global growth could be derailed."

That at bottom is what the markets are worried about.

- Published19 January 2016

- Published19 January 2016

- Published19 January 2016

- Published29 December 2015