Four ways Nasa is teaching us how to live more sustainably

- Published

Astronauts who spend months on end in orbit have to learn to make do and mend in the best tradition of sustainability.

Missions to bring fresh supplies are expensive and time consuming. For any astronauts who take on a mission to Mars, planned for the 2030s, with the round trip likely to take two years, life would be even tougher.

That prospect has helped focus minds at America's space agency, Nasa, on clever ways to provide for daily needs in challenging conditions. But the lessons being learned are also proving to have knock-on benefits down here on Earth.

As Cady Coleman, a current Nasa astronaut and innovation lead, explains: "We basically have a limited environment in space, and it causes us to think about how we get stuff there, how we maintain it, and how we get most use out of it."

Ms Coleman says space can be a fantastic "technology accelerator" - and that sustainable technologies devised by Nasa often find themselves repurposed for use on Earth.

Astronaut Cady Coleman has been leading Nasa's extensive efforts on sustainability

Firms such as Nike, DIY giant Kingfisher and Ikea are already pursuing so-called closed loop business models - where waste is eliminated through repurposing and recycling - in the hope of being greener and cutting costs. And with pressure on water and fertile land growing, farmers are seeking less input-intensive methods.

So what can be learned from Nasa's research?

1. Growing food

Take Nasa's decades of research into growing vegetables in space, which culminated in astronauts harvesting and eating lettuces aboard the International Space Station (ISS) last year.

Astronaut Steve Swanson harvests a crop of red romaine lettuce plants on the ISS

The crew grew the produce in "seed pillows" - a modified version of the common grow bag - and used specially designed, energy-efficient LED lights to power photosynthesis, an idea that originated with Nasa back in the late Nineties.

The lights, which use more growth-inducing red and blue-coloured LEDs than green ones, have also become instrumental in the rise of so-called vertical farming back on Earth, a highly sustainable form of agriculture.

Such farms grow produce on shelves indoors to optimise use of space and water, and could help feed a rapidly growing global population, external in the future, say proponents.

Green Sense farm near Chicago, for example, re-uses most of its water, is about 10 times more space-efficient than a traditional farm, and harvests 26 times a year compared to the usual two or three.

Nasa's lights, which use more red and blue LEDs than green, are used by vertical farms on Earth

"NASA's need to conserve all resources in space has caused technologies to trickle down to earth," says Green Sense's chief executive Robert Colangelo.

"A good example is energy and heat-saving LED lights that maximise photosynthesis. We have also developed a closed-loop system for capturing nutrient water and evapotranspiration from plants, inspired by NASA water management systems."

2. Clean water

In space, water is in short supply, so Nasa has developed an innovative way to filter waste water on the ISS using chemical and distillation processes. This lets it turn liquid from the air, sweat and even urine into drinkable H2O.

The International Space Station has been continuously occupied by humans since 2000

In fact, since 2008, more than 22,500 pounds of water have been recycled from urine alone on the ISS - something that would have cost more than $225m (£160m) to launch and deliver to the station from Earth, external.

"Most people are horrified when they see what we drink!" says Ms Coleman. "But the filtered water up there just tastes beautiful, it really is delicious."

Nasa has since licensed the technology to companies on Earth, which have created portable filters for use in places where fresh drinking water is scarce.

Filters produced by US firm Water Security Corporation, for example, have been installed in villages across Mexico and Iraq, allowing residents to purify water from contaminated sources.

Filters featuring Nasa technology are helping people in rural Mexico access clean drinking water

"The inspiration to use this technology in… developing countries was directly related to what was required for it to be successful in space," says Ken Kearney, vice president of sales and marketing.

"It is incredibly reliable and requires no skilled maintenance. It can be deployed in regions where there is little or no electricity, using only gravity pressure to push water through the system."

Nasa is also funding research into whether human faeces can be recycled into food on long space missions - although it seems unlikely that such an extreme solution would catch on back on Earth.

3. Recycle your tools

But Nasa's efforts go way beyond food and drink.

Ms Coleman points out that "down here, we can pretty much all go to the hardware store to buy tools - but our situation in space drives us to be more resourceful and to renew, reuse or recycle tools."

As such, Nasa is experimenting by 3D printing tools out of hard plastic on board the ISS.

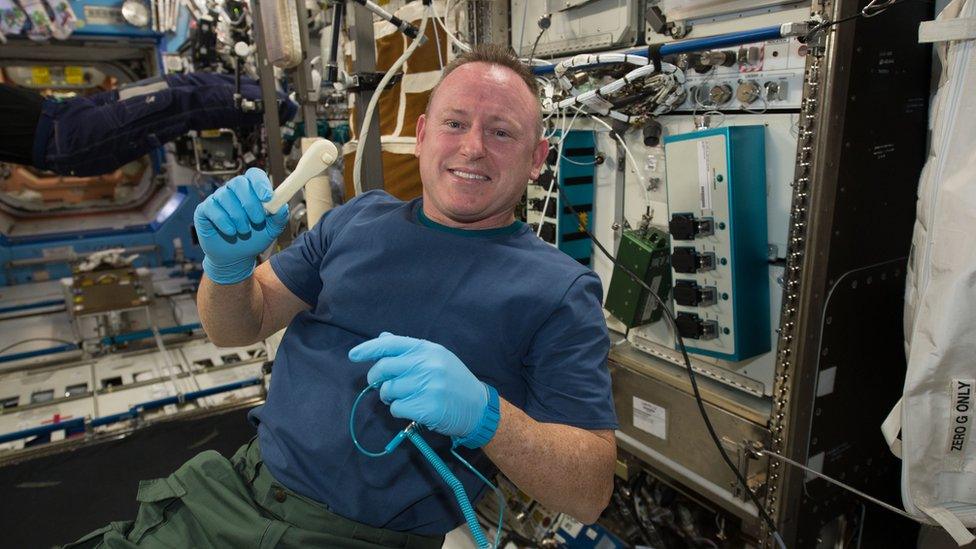

Astronaut Barry Wilmore shows off a ratchet wrench made with a 3D printer on the ISS

"We could need a tool, get a design for a tool sent up, print a tool and then reuse that material to print other tools," says Ms Coleman.

Researchers from NASA's Ames Research Centre in California are also looking into the problem of litter, which can clutter up a shuttle or space station, external.

Crews try to avoid jettisoning trash in space, as it can create a hazard for other spacecraft and contaminate planets or moons. And so Nasa is testing a trash compactor that melts down rubbish, such as plastic water bottles and foil drink pouches, transforming them into eight-inch-diameter tiles.

These could potentially be used to strengthen radiation shielding on a spacecraft.

4. Green buildings

Nasa's technology could lead to greener buildings down on Earth, too.

Nasa's Ames centre has constructed a green building on its campus in Moffett Field, California, where energy-saving technologies of the future are being tested.

Sustainability Base leaves "virtually no footprint" and uses several innovations from space, including solid oxide fuel cells of the type found on Nasa Mars rovers to generate electricity, and a system that reuses wastewater to flush toilets.

These buildings represent the culmination of an overall philosophy that consuming resources should be done, wherever possible, according to closed loop principles, without exhausting supplies or creating unnecessary waste.

- Published13 April 2016

- Published6 April 2016