Off target: Is it the end of 'Abenomics' in Japan?

- Published

Are we witnessing the end of "Abenomics"? Has Japan's grand attempt to reflate the world's third largest economy failed?

In the last two weeks we've seen the country's central bank, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) cross in to uncharted territory, pushing interest rates below zero for the first time ever.

In just two days last week the Japanese stock market tumbled nearly 8%, erasing most of the gains of the last two years. The latest GDP figures show the Japanese economy is shrinking again.

All of this is bad news for Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his right hand man, central bank governor Haruhiko Kuroda. But is it their fault? And is their project now doomed?

There has been a lot of hyperbole surrounding the Abenomics project. The Bank of Japan's vast money printing project has been described as a "money-spewing bazooka".

Governor Kuroda has repeatedly said he will do "whatever it takes" to defeat 20 years of deflation. But the core of Abenomics is not reflation; it is weakening the Japanese currency, the yen.

The three arrows: explaining Abenomics

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's economic policy, which quickly became known as "Abenomics" is based on three arrows:

The monetary arrow: expansion of the money supply to combat deflation

The fiscal arrow: increased government spending to stimulate demand in the economy

The structural arrow: structural reforms to make the economy more productive and competitive

'No growth engine'

Why? Because Mr Abe and his advisors know that the only easy way to get Japan growing again is to increase exports.

"There is a small group who still believe Japan can reflate its economy and regain its animal spirit" says Martin Schulz, chief economist at the Fujitsu Research Institute, "but very few believe this.

"There is no growth engine left in Japan. So exports are the most important part of growth."

Martin Schulz says that for every 1% Japan's economy grows, between 0.5 and 0.7% comes from exports.

The reason is simple. Japan's population is growing old and shrinking. By 2020 it will be losing around 600,000 people a year. Getting growth from of an ageing, shrinking society is extremely hard.

Japan's stock market falls have erased most of the gains of the last two years

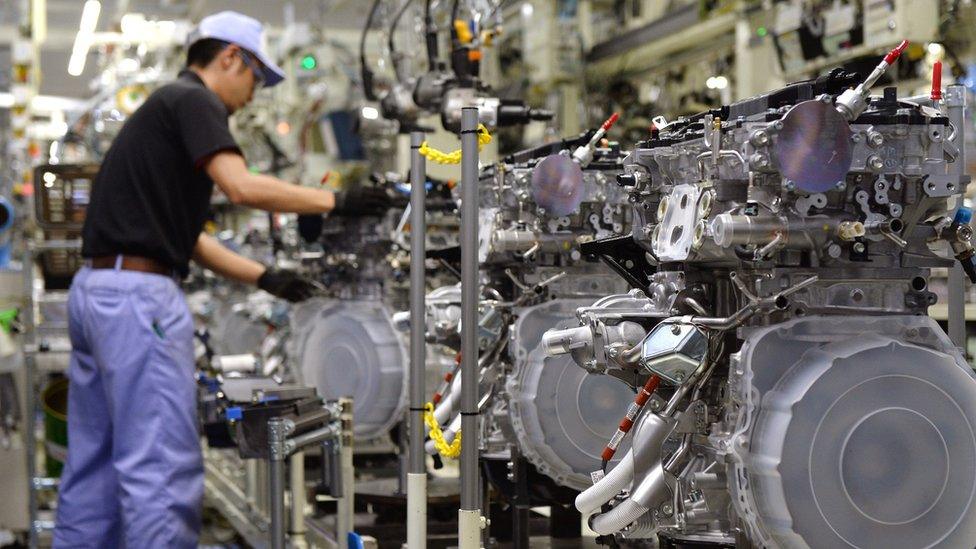

But Japan is still a mighty industrial power. Make Japan's goods cheaper, goes the theory, and foreigners will want to buy more of them.

Falling yen

And so, between 2012 and 2014 the value of the yen against the US dollar was deliberately driven down - from around 80 yen to the dollar to 120 yen to the dollar.

For Japan's big exporters it has been Christmas every day. In 2014 Toyota reported a record profit of $18bn.

But two things are now spoiling the party. First, the yen is suddenly getting stronger again. Second, Japan's corporations are stubbornly refusing to spend their windfalls.

For the Japanese government the strengthening currency is by far the bigger worry. In the last two weeks the yen has shot up - from 120 yen to the dollar, to 112 yen to the dollar.

For Japan's government, the strengthening yen is a worry

This prompted BOJ Governor Kuroda to take the dramatic step of announcing negative interest rates for the first time ever.

"The Bank of Japan had no intention of instituting negative interest rates until the yen started strengthening" says Martin Schulz.

The sudden rise in value of the Japanese yen is being driven by problems elsewhere; in Germany, the United States and China. When the world economy runs in to trouble, investors head for "safe havens" and Japan is one of them.

Cash piles

By pushing interest rates below zero the Bank of Japan is telling investors they will lose money by parking it in Tokyo.

If the yen continues to strengthen Mr Kuroda could push the negative rate even lower, to -0.5% or more.

The negative rates are also aimed at Japan's giant banks and corporations.

"A lot of Japan's corporations have cash piles larger than their stock market valuations," says Ed Rogers, chairman of Rogers Investment Advisors in Tokyo.

Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda has pushed interest rates below zero for the first time

"The Bank of Japan's quantitative easing (QE) programme has been trying to put liquidity back in to the economy.

"Negative interest rates are aimed at making them do something different with their money."

But banks and corporations have been hoarding the cash, using it to repair holes in their own balance sheets.

Ed Rogers estimates the Japanese corporate cash pile could amount to $3 trillion.

If some of it were spent on bigger dividends for shareholder, or increasing wages for employees it could dramatically boost Japan's eternally sluggish domestic consumption, he says.

"This is aimed at changing the way corporate Japan conducts itself, to change the way it functions, to make it more shareholder friendly, more employee friendly.

"Negative interest rates show Abe and Kuroda are committed to structural change in Japan," he says.

Japan's companies are sitting on cash piles of about $3 trillion, say some

Shrinking population

Others are less bullish. They believe the failure of Japanese corporations to raise wages or invest more at home is perfectly logical.

"Corporate mangers are pessimistic about the long term economic outlook," says Takuji Okubo, chief economist at Japan Macro Advisors.

"They believe Abenomics will come to an end, and Japan will return to deflation. The working population is shrinking.

"So in the medium to long term they have good reason not to raise wages or hire new people."

Martin Shulz agrees.

"What the Bank of Japan is doing may work in a young economy," he says, "but it doesn't work in an old economy. It is pushing companies to invest. But they will not invest in Japan, they will go overseas."

During the last three years Mr Abe's has made much of Japan rediscovering its "animal spirit". Instead he is finding out the truth in the old adage that "demographics is destiny".

With falling birth rates, Japan's population could drop to 97 million by 2050 - 30 million fewer than now

'Resistant to innovation'

"Prime Minister Abe is against immigration, so he is partly to blame" says Takuji Okubo.

"Japan needs to welcome immigrants, but Prime Minister Abe's cabinet is largely made up of right wing nationalists, so it's not going to happen."

Japan is not about to disappear. It is still the world's largest creditor nation by far. Japan's big export corporations are still among the strongest in the world.

But it has a mature economy, with a rapidly ageing and shrinking population. Its domestic companies are also old, deeply hierarchical and run by old people who are resistant to innovation.

Japan's wealth is largely in the hands of elderly people who want to preserve their assets and fear inflation.

None of this suggests Japan is about to rediscover its animal spirit.

- Published15 February 2016