Life after oil: can Aberdeen rise again?

- Published

Off the coast of Aberdeen, a dozen oil supply ships sit idly, their crews waiting for word of work.

From their decks, the commodities that once made this Scottish city a centre of commerce are still visible - the grand granite buildings of Union Street, and the few remaining fisheries in a harbour dominated by fuel storage cylinders.

One of those is co-run by James Robertson. Founded in 1892 by James's ancestor, Joseph, the firm has been in family hands for four generations.

In the 1970s and 1980s, when the North Sea energy boom began to drive up costs for local businesses, and the Cod Wars led to restrictions on fishing quotas, Joseph Robertson Ltd had to adapt to survive.

"We used to fillet fish," Mr Robertson says, but limited expansion meant that soon became unprofitable.

"Now we process fish cakes and frozen breaded fish for some of the UK's largest supermarkets".

But it's the North Sea oil industry, which fuelled Aberdeen's economy for more than four decades, that is now facing a similar challenge - adapt or die.

Aberdeen's high cost of living means some former oil industry employees have had to use local food banks

And, unlike granite and fishing, which faded slowly over a couple of decades, the pace of the fall in the oil price - from $120 a barrel to around a quarter of that in less than two years - has taken almost everyone in the city by surprise.

Just a couple of years ago, house prices in "the energy capital of Europe" were rising faster than in London. And the energy sector was so strong, that the impact of the global recession of 2008 was hardly felt.

Prior to the collapse in the oil price, it was said that if you wanted a job in Aberdeen, you got one.

Now, it has one of the fastest-rising rates of unemployment in the UK. An estimated 65,000 oil and gas jobs have been lost since the downturn began in 2014, and the number rises on a weekly basis.

Oil rebound

The redundancies are made all the worse by the fact that the cost of living in Aberdeen is still high, powered by the six figure salaries that were commonplace in the oil sector just a couple of years ago.

"Many people are living above their means," says Dave Simmers, who runs a food bank as part of Community Food Initiatives North East, which has handed out staples such as cereals, rice and frozen fish to some former oil high-fliers in the last few months.

"They are two or three wage slips away from a brick wall."

Nonetheless, almost everyone you meet in Aberdeen is convinced that oil will rebound, if not to the heady heights of $120 a barrel, then at least to a level where the North Sea operations can be profitable again (somewhere between $60 and $80 a barrel, depending on whom you ask).

Aberdeen's Robert Gordon University still has one of the highest graduate employment rates in the country

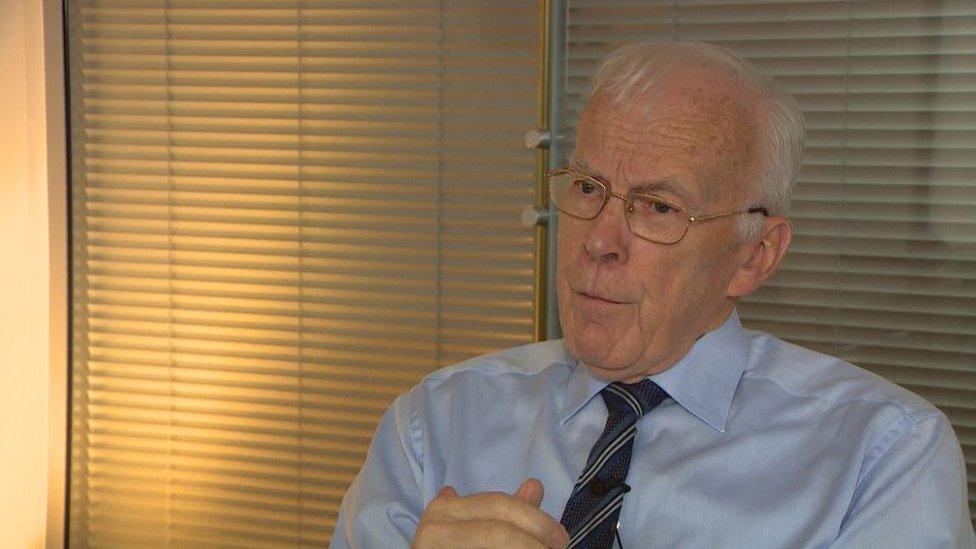

When it does, argues Sir Ian Wood, Aberdeen will still have some advantages.

Sir Ian, a billionaire-turned-philanthropist who made his fortune in North Sea oil (the family business was once fishing) says that while reserves are depleting, the Aberdeen-based industry could be "exploiting a million barrels a day" for some time to come.

Plus, the fact that it's a "politically and economically stable" region, especially when compared with other oil hotspots such as West Africa, will work in the city's favour, he says.

Most significantly, multinational operators in the North Sea were forced to do more with less as the oil price plummeted.

"The good news is the costs have been reduced," says Sir Ian.

"Our operating cost base is down something like $15 a barrel. That's a huge reduction."

Read more on Aberdeen and oil:

Expertise counts

But the future of Aberdeen's association with oil does not necessarily depend on how quickly the platforms begin pumping again.

"Whatever happens to the oil industry," Prof Ferdinand von Prondzynski, the vice-chancellor of Aberdeen's Robert Gordon University says, "there is going to be some aspects of it that will remain very important here for a long time to come - decommissioning being an obvious example."

For the university, which offers a plethora of postgraduate energy degrees (and still has one of the highest graduate employment rates in the country), expertise may become more important than the black gold itself.

"Next to the UK, the largest number of people working in the oil industry in Europe are in France," Prof von Prondzynski adds.

"France has no oil. If you look at Houston, it is still recognised by most people as the global centre of the oil industry, but there is no oil - only very minor amounts are left now.

"It's not necessary to actually have the natural resource there."

Aberdeen fish processing firm Joseph Robertson has found it easier to both recruit and retain staff

The woes of the oil industry have also had a positive effect on some local businesses, which found it hard to compete for labour when generous salaries were the norm.

"Prior to this we struggled to get people to come and work for us," says James Robertson, of fish processors Joseph Robertson.

"Our staff turnover was something like 30% a week - now it's around 5%. We've got access to some skills that we weren't able to access before."

Tourism is another beneficiary. Steve Harris, the chief executive of Visit Aberdeen, says it used to be "really hard for people to afford to come and get a hotel room" in the city, but "that's not the case anymore."

And those who do visit for something other than oil often do so to take in another treasure of the North Sea.

"It's a little known fact that Aberdeen is the best spot in Europe for dolphin watching," explains Steve, standing on the edge of the harbour, battered by the heavy hibernal winds.

"We got a bit obsessed by oil."

- Published18 January 2016

- Published14 January 2016

- Published13 January 2016

- Published3 December 2015