Goodbye Westminster, more power to the people?

- Published

What would Manchester's Sir Joseph Heron have done?

Sir Richard Leese, the Labour leader of Greater Manchester, doesn't need telling that English councils are dominated by central government. He lives with it every day.

Which is why he and leaders of the 10 councils that make up Greater Manchester have led calls for English devolution.

The building of Greater Manchester's Metro light railway illustrates what's wrong, says Sir Richard.

"To invest in light rail in Greater Manchester we've had to go to government with a begging bowl.

"That a conurbation of 2.7 million people can't make its own decisions about whether it's going to have a light rail system or not is absolutely ludicrous."

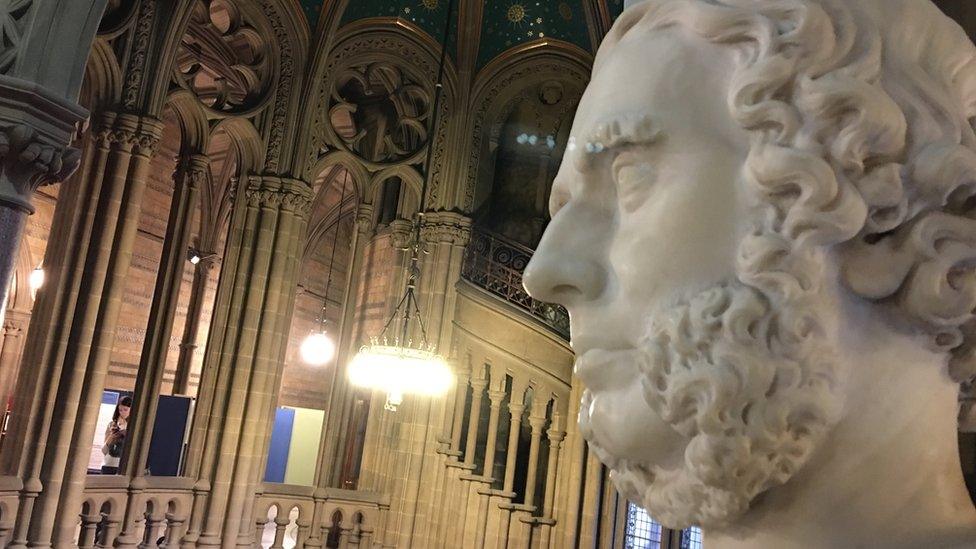

It's a situation which would doubtless have dismayed Victorian Manchester's formidable, long-serving first Town Clerk Sir Joseph Heron.

Sir Joseph Heron's view was that "the Manchester way was best" says Martin Hewitt

"Heron was a man contemporaries spoke about in hushed tones," says Huddersfield University's Professor Martin Hewitt.

"He was quite happy to stand up to civil servants and politicians in London and tell them the Manchester way was the best way."

Sir Joseph brought clean water to the fast-growing city by constructing the Longdendale chain of reservoirs - then the largest such project in the world.

Drive to the sea

Civic leaders then set about connecting their once land-locked city to the sea.

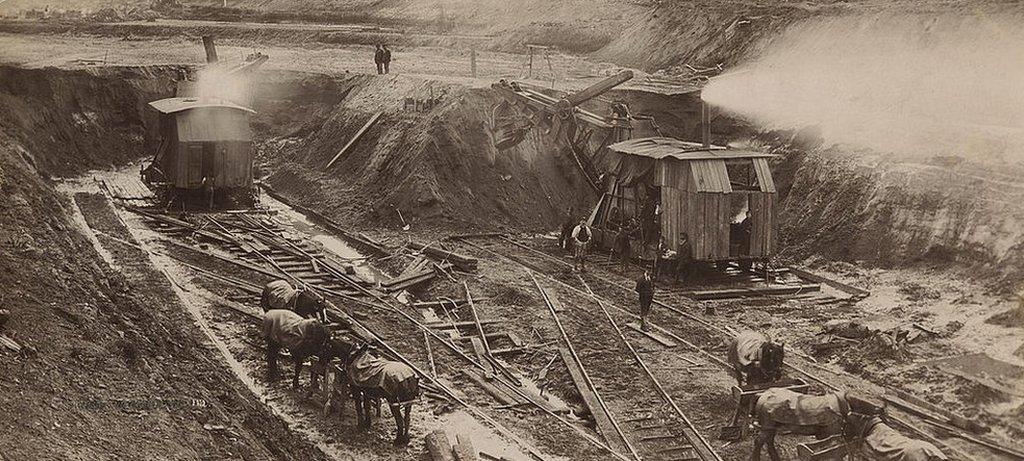

Funded by the council and local merchants, the 36 mile-long (58km) Manchester Ship Canal was big enough for ocean-going cargo vessels to steam right into the city centre when it opened in 1894.

It took six years to build the Manchester Ship Canal: This is the cutting at Irlam, Salford

The steam yacht Norseman led the procession at the official opening of the canal in January 1894

At its peak in 1958, the canal was handling about 18m tonnes of freight a year

"It was the Channel Tunnel of its era. It was an absolutely enormous engineering and financial scheme," says Prof Hewitt.

Self-reliance was the ethos of the age, he adds.

"Manchester in the 19th Century raised the money it needed and spent the money it raised. And did so without any government support."

As ship sizes grew in the 1960s usage of the canal declined, but Peel Ports is now planning to redevelop it - with the canal handling 100,000 shipping containers by 2030

But the autonomy councils like Manchester once enjoyed was about to begin a long-term decline.

Power shift

After 1945, the reforming post-war Labour government sharply curtailed their independence.

Council-owned hospitals were absorbed into the newly-formed NHS, and their gas and electricity services became part of new nationalised industries.

Successive Conservative and Labour governments then required councils to deliver improvements in public health, education, housing and social care - which were mostly funded by grants from central taxation.

In the postwar era, successive Conservative and Labour governments took away local councils' financial independence

Professor Tony Travers of the London School of Economics, says as grants grew in the 1950s and 1960s, the relationship between central and local government changed.

"You began to get what you might call the 'he who pays the piper calls the tune' argument.

"Ministers think 'hang on, we're providing local government with all this money through these huge grants and yet they don't do what we want'."

By the end of the 1970s, local governments raised about half their budgets from domestic and business rates. The rest came from central government.

Thatcher vs Livingstone

But their local financial foundations were about to be weakened further.

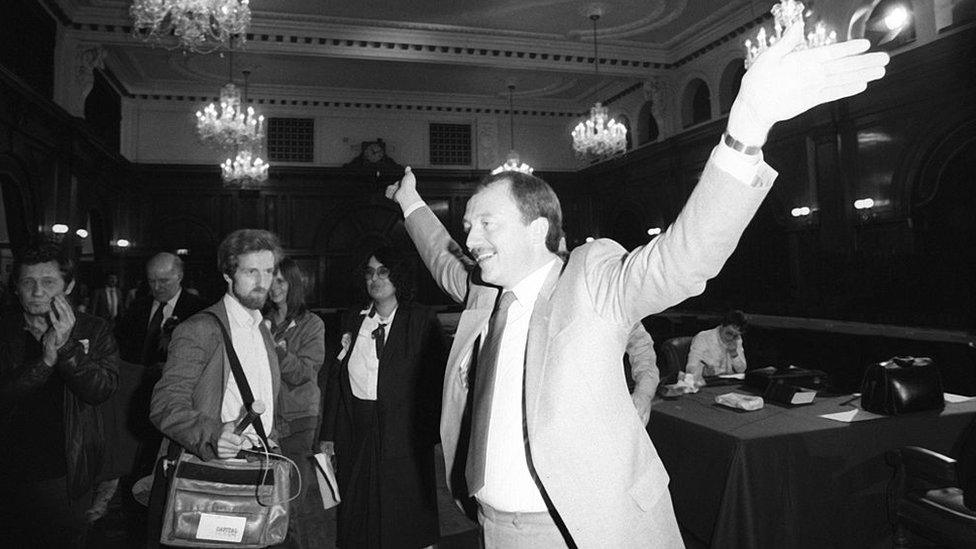

The battle between central and local government was epitomised by the standoff between Mrs Thatcher and then GLC leader, Ken Livingstone

The early 1980s saw bitter battles between the radical Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher and what she saw as "loony left" councils then running major cities - in particular the Labour-controlled Greater London Council under Ken Livingstone.

Mr Livingstone was determined to deliver his "Fares fair" election promise of big cuts in London commuter costs paid for by sizeable increases in the rates. Margaret Thatcher was equally determined to stop him.

Mrs Thatcher finally prevailed, abolishing the GLC and six metropolitan councils in other cities, and went on to take business rates out of council control entirely.

County Hall London, the former headquarters of the GLC - which was abolished in 1986

Councils now had to hand over the business rates they collected to Westminster, to be redistributed as ministers and officials saw fit.

'Super control'

By this single measure the funds councils raised locally fell from around 50% of their budgets to just 20%, says Prof Travers.

"It was a very big change. Councils were now very heavily dependent on central government funding and the amount of freedom they had with their own tax was virtually none."

Catherine Staite of Birmingham University's Institute for Local Government says the consequences went beyond pure finance.

"Councils were trapped in the persona of the needy, of the dependent.

"It created a psychology of victimhood and a narrative of excuses. 'Our people aren't well educated, so what can we expect?' or 'we can't attract businesses so what can you expect?' "

"We became very good at demonstrating our levels of deprivation," says Blackpool's Labour leader, Simon Blackburn

Councils now had to bid for central government funding to deliver programmes which were also increasingly laid down by Westminster.

A system was developed to determine how much each council would get - theoretically allocating the largest grants to those which demonstrated the greatest need - a methodology Prof Travers compares to central planning in the USSR.

"It was the absolute top end of super-control - the more paradoxical and Alice-in-Wonderland because of Mrs Thatcher's fearsome reputation as a deregulator and liberaliser."

Poor returns

In Blackpool, one of the most deprived councils in the land, the competition for funds motivated councillors of all parties to highlight problems which matched grant criteria, says Labour leader Simon Blackburn.

"We became very good at demonstrating our levels of deprivation: crime, poverty, poor health - you name it.

"With the benefit of hindsight, it was always slightly depressing".

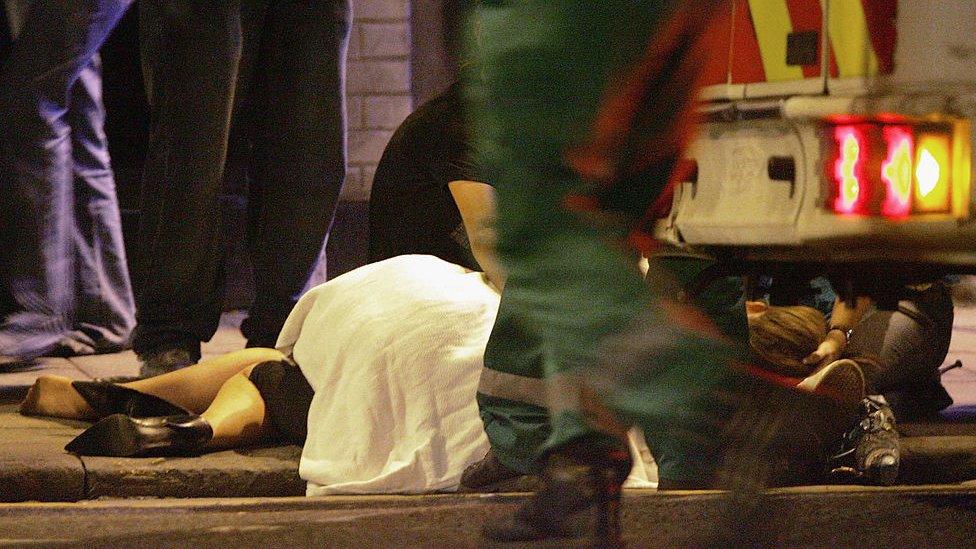

Central government drives to cut binge-drinking are not working - local initiatives would be more effective, argues Blackpool's Simon Blackburn

Cllr Blackburn says a recent report on the outcome of these centrally-determined programmes shows poor returns on the money spent.

"We've been spending millions of pounds every year trying to persuade people not to drink to excess," he says, yet drink-related hospital admissions have gone up every year.

"We can't continue to tolerate a situation where vast sums of public money are spent with no tangible outcome."

Cllr Blackburn is part of a new generation of council leaders who believe locally determined solutions to local problems will prove far more effective than central government control.

Restoring more decision-making powers to local councils makes sense, argues Manchester's Sir Richard Leese

Which is why despite continued widespread opposition to his austerity cutbacks, George Osborne's devolution proposals have supporters across the political spectrum.

Osborne's powerhouse

Manchester's Sir Richard Leese is well aware of the political risks - that councils rather than the government end up being blamed for effects of continued centrally-imposed funding cuts.

He says it's a risk worth taking in return for genuine devolution.

"The government's austerity programme is going to continue to happen with or without devolution.

"The question is how do we make whatever circumstances we are in work better for people in Greater Manchester?

"I'm absolutely convinced we are more likely to make even the most unpleasant circumstances work better if we're making the decisions."

George Osborne plans to give English cities more powers as part of the 'Northern Powerhouse' plan

In his speech to the Conservative Party conference in Manchester last autumn, George Osborne announced a reversal of Margaret Thatcher's business rate centralisation.

In future, councils will be allowed to keep the proceeds of increases in their business rate base. When the chancellor's new system is fully in force in 2020, central government grants to councils will have been phased out entirely.

For the first time in decades councils will have a positive incentive to increase their business rate base, says Prof Tony Travers.

"The new system means you have to build your economy to get more money because there will be no more central grants."

There are still-unanswered questions about how the new system will work.

But while Manchester may be ready for a transfer of powers, not all boroughs are as prepared

With big differences in councils' ability to attract businesses, how wide will the differences between richer and poorer councils be allowed to become?

Long march reversed?

There are practical difficulties too. Most councils have only just begun to form themselves into combined authorities like Greater Manchester which Mr Osborne says is a requirement for significant devolution to be agreed.

And critics say current proposals to force through council house sales or to stop council pension funds following an ethical investment policy are a sure sign that Westminster is finding it hard to let go.

But for all the limitations, it does seem a corner has been turned in the long march to centralisation.

The chancellor's proposals may still be a long way from the more secure financial footing local government enjoys in most developed nations elsewhere.

But with momentum behind the shift to localism growing, it looks like it's a change which is likely to prove difficult for future governments to reverse.

For more on this, listen to Michael Robinson's Analysis: Power to the People? on Radio 4 at 20:30 on 7 March and repeated at 21:30 on 13 March 2016.