Maid in Brazil: Economy troubles push women back into old jobs

- Published

Mrs Souza has never worked as a maid before but has bills to pay

Last week, Aloisa Elvira de Souza walked into a job centre specialising in finding maids for middle-class families in Brazil.

A few years ago, Mrs Souza might have gone to the agency to look for a maid - not to offer her services as one.

She has spent the past 12 years working in the Greater Sao Paulo area's metalworks industry, where salaries are on average three times higher than those of domestic workers.

Mrs Souza has never worked as a maid and seems overqualified for a job cleaning houses, ironing clothes, taking care of children and cooking.

But she cannot afford to be picky right now. Her debts are piling up, from health insurance to her daughter's college tuition.

"I have bills to pay every month, so I thought getting a job as a maid would be the solution," she says.

"I don't have formal experience, but I do this sort of work in my own home. So why not?"

Economy in reverse

Brazil is going through its worst recession in more than two decades.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts the country's economy will have contracted by almost 8% in two years by the end of 2016.

Brazil soared in the past decade, as one of the emerging Brics economies, when its commodities were hot property in the international markets.

But with China slowing down and commodity prices reaching record lows, Brazil's economy went into reverse at high speed last year.

President Dilma Rousseff - from the governing Workers' Party - tried to delay the effects of the recession in the labour market and pumped stimulus money into the economy through tax breaks and subsidies.

But now those policies, intended to protect workers, are doing the exact opposite.

Brazil's debt grew, and the country lost its investment-grade credit rating as well as consumer and investor confidence.

And workers' situations have deteriorated rapidly in the past few months.

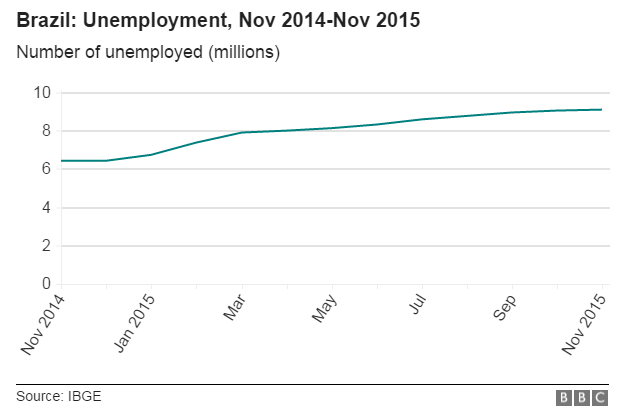

In just one year, the number of unemployed people jumped 41% - from 6.4 million people to 9.1 million.

Brazil went from a situation some economists consider full employment, external, back in early 2014, to 9% unemployment now.

Wages increased in that period, but inflation rose almost twice as fast, so most workers are now worse off.

Symbol of change

A closer look at Brazil's economy reveals some worrying trends.

Domestic workers are a symbol of that change.

Brazil is the country with the highest number of domestic workers in the world. Six million people - more than 90% of them women - work as maids.

Not long ago, the number of people in domestic jobs was falling - but many women are once again applying to be maids

A few years ago, when Brazil's economy was flourishing and the country needed workers to fill all the new jobs, women began leaving domestic service to work in industry and shops.

In 2011, Brazil's Finance Minister hailed domestic workers as a "sub-utilised" labour reserve - an army of women who could gain skills and enter the job market filling better roles, with higher wages.

And that really did happen.

From 2007 until last year, the percentage of people working in domestic jobs fell - from about 8% of Brazil's workforce to below 6%.

Middle-income families were left with the choice of either paying higher wages to their maids or doing their own cooking and cleaning.

Going back

But now there are signs that this trend is in reverse.

More women are finding themselves in Mrs Souza's position: losing their jobs in industry and commerce and moving into less skilled jobs with lower wages, many of them returning to roles they thought they had left behind.

Simone Fernandes considers herself lucky to have a job at all

Simone Fernandes spent Brazil's boom years working in a supermarket. She thought her days as a maid were over, but now she is back working for a middle-class family.

"Back then things were getting better," she says.

"You had many job offers. You knew that when you left a job, you'd be quickly employed less than a month later.

"Also, you could go to your boss and he would give you counteroffers. But that was then. Now, you have to be happy to just have a job."

Black market

Daniele Kuipers, who set up Casa and Cafe, a website that helps maids find jobs, says the number of women offering their services grew a staggering 92% last year, as Brazil's recession deepened.

But the demand for domestic servants did not grow.

Daniele Kuipers says the number of women domestic workers on her website almost doubled last year

Middle-income families are cutting their expenses because of the crisis too.

During the boom years, Brazil updated its domestic service laws, increasing protection for formal workers.

This should have been good news - but, in the current recession, it has only increased costs for hiring maids formally.

As a result, Fernando Souza, owner of the Prendas Domesticas job agency, says, there is huge growth in the number of informal domestic workers, who get lower wages and are not collecting their social security payments.

This growth in black market jobs is a trend for all workers in Brazil, not just maids. In one year, Brazil lost one million formal jobs.

Many people are moving into the black market, not just as domestic workers, but also as street vendors

Silver lining?

Brazil's prolonged recession is having dire consequences for the poorer classes.

Mrs Fernandes and her husband had to sell their car and move into a smaller flat.

They are working longer hours - but, with prices rising on a monthly basis, their standard of living is declining rapidly.

There may be one silver lining, though, for some of these families who were emerging socially but are now sinking again.

During Brazil's good years, both Mrs Souza and Mrs Fernandes managed to get their children through college.

That means the next generation of workers may be more skilled than the current one.

Brazil's challenge for the future will be to create new skilled jobs for them.

Additional reporting by Ruth Costas, BBC Brasil.

- Published5 February 2016