How impulse shopping led to a multi-million-pound business

- Published

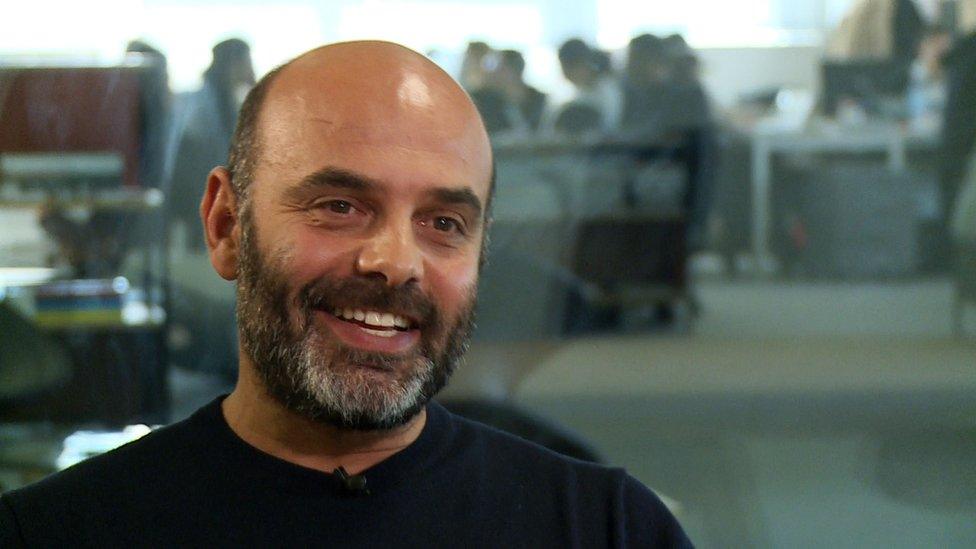

Sebastien Fabre says his wife's impulse shopping provided the inspiration for Vestiaire Collective

Inspiration for an entrepreneur often comes when they look for something - a service or a product they need - only to find it doesn't yet exist.

In Sebastien Fabre's case it was his wife's impulse shopping that provided the inspiration that led to the creation of Vestiaire Collective - an online marketplace for second-hand goods.

Mr Fabre, then a Microsoft executive, freely admits he knew nothing about fashion when he got married. But he did know that his wife, who enjoyed shopping, had a lot of bags.

And because she worked in the fashion industry, these impulse purchases weren't just any old bags, but high-end designer ones from the likes of Chanel and Hermes. Yet, despite having so many of them, 13 to be exact, she used just one. The rest languished, unused, in the wardrobe.

"There's a lot of treasure sleeping in the wardrobe of people," says Vestiaire Collective founder Sebastien Fabre

Together they decided to sell them, but despite the plethora of second-hand marketplaces already in existence, such as eBay and Amazon, they couldn't find anywhere where they felt their credentials as a seller would be trusted and where the bags' value would be recognised.

It sparked an idea. Rather than accept the status quo, and suspecting it wasn't just his wife who had unused designer items, Mr Fabre decided to do something about it.

Six months later, having roped in five other people, he established Vestiaire Collective - an online marketplace for second-hand designer bags, shoes, accessories and clothing. The first thing they listed for sale? His wife's handbags.

Web developers don't typically know the name of a Birkin bag - the handbag named after actress and singer Jane Birkin - says Vestiaire Collective founder Sebastien Fabre

Eight years after its 2009 foundation - at the height of the financial crisis - sales are growing 85% year-on-year. "There's a lot of treasure sleeping in the wardrobe of people," Mr Fabre says.

It has four million members in over 40 countries and last year its sales totalled some €77m (£59m). It makes money from the commission it charges customers on sales. Typically this is 25%, or for those who use its concierge service, which photographs and lists products on customers' behalf, it takes 35%.

The rapid growth is not bad for someone who until he set up the business had been working in tech and knew absolutely nothing about fashion.

But Mr Fabre says he was aware of this weakness all along - and deliberately ensured that three of the five co-founders he bought on board had fashion backgrounds.

And while he admits it's "pretty tricky" for a website developer to know what, for example, a Birkin bag is, he believes it's important for the whole team - whether on the fashion side or on the development side - to understand the type of products they are selling.

Vestiaire Collective checks all items sold are authentic before sending them to customers

Around a third of products offered for sale are rejected by the firm

The online revolution has driven the development of many similar websites.

Rivals to Vestiaire Collective include Edit Second Hand, Hardly Ever Worn It, and High Society. Yet the size of the growing market for upper premium brands still makes it attractive, with the sector valued at €16bn, according to management consultancy Bain & Co.

Mr Fabre believes the firm's focus on authenticating the products and ensuring they are in good condition is helping it to stand out.

Unlike broader online auction sites, anyone who wants to sell an item via their website first needs the company's approval.

A potential seller will email in photos of their product alongside a description and the price they want.

This will then be checked by an in-house team to see if it's suitable, considering factors such as whether it's an appropriate brand, on trend and of sufficient quality. Around a third of potential items are rejected. Vestiaire Collective will then crop the photos before posting them on its site.

'We control everything'

When an item is bought, the seller sends it not to the customer but to the firm which will check it's the real deal and in a good condition before sending it to the buyer. The entire process takes around seven days.

But it's this service which Mr Fabre believes makes its offering more unusual.

"We control everything, so 100% of the product goes through our hands before going to the final buyer," he says.

Vestiaire Collective co-founder Fanny Moizant says they were inspired by luxury designer fashion website Net a Porter

The aim also - in this high end world - is to make all the items and the website itself look like a designer - rather than a used goods - website.

Fellow co-founder Fanny Moizant says its inspiration was luxury designer fashion website Net-a-Porter rather than the existing second-hand online shops.

"I even had some people saying 'oh my god I didn't even spot it was second hand', so people might think it's another online retailer selling new pieces. We tried as much as we can to combine those two," she says.

In exchange for a higher commission charge Vestiaire Collective collects, photographs and lists members' items for them

Despite this, both Mr Fabre and Ms Moizant argue that their offering complements rather than rivals that of the existing designers.

Mr Fabre says the firm provides an opportunity for someone to buy an item that is no longer available, provides money for people to reinvest in new designer items and offers accessible prices for those new to designer buying.

"We're building the value and respecting the value of the luxury market. It also keeps up the value of fashion items," he says.

Peter York, who has advised many large luxury companies, agrees, noting that one of the criteria used to define a luxury product is that the item holds its value.

But he warns the concept of second-hand luxury won't appeal in all markets across the world.

"I think they have a chance amongst more evolved kinds of consumers in the West. You know, if you come out of a tough world you don't want second-hand; second-hand implies poverty," he says.

Mr Fabre is undaunted, comparing the still relatively fledgling world of second-hand fashion with that of the more established car industry. He notes that people routinely trade in their old cars for newer models.

Is that his next move?

Mr Fabre laughs, aware of the dangers for a start-up of expanding too quickly. "My investors like to remind me that I have to focus on my core business first," he says.

This feature is based on interviews by Life of Luxury series producer Neil Koenig