How much cash is the US raising from tariffs?

- Published

Donald Trump has delivered a profound shock to the global trading system since returning to the White House.

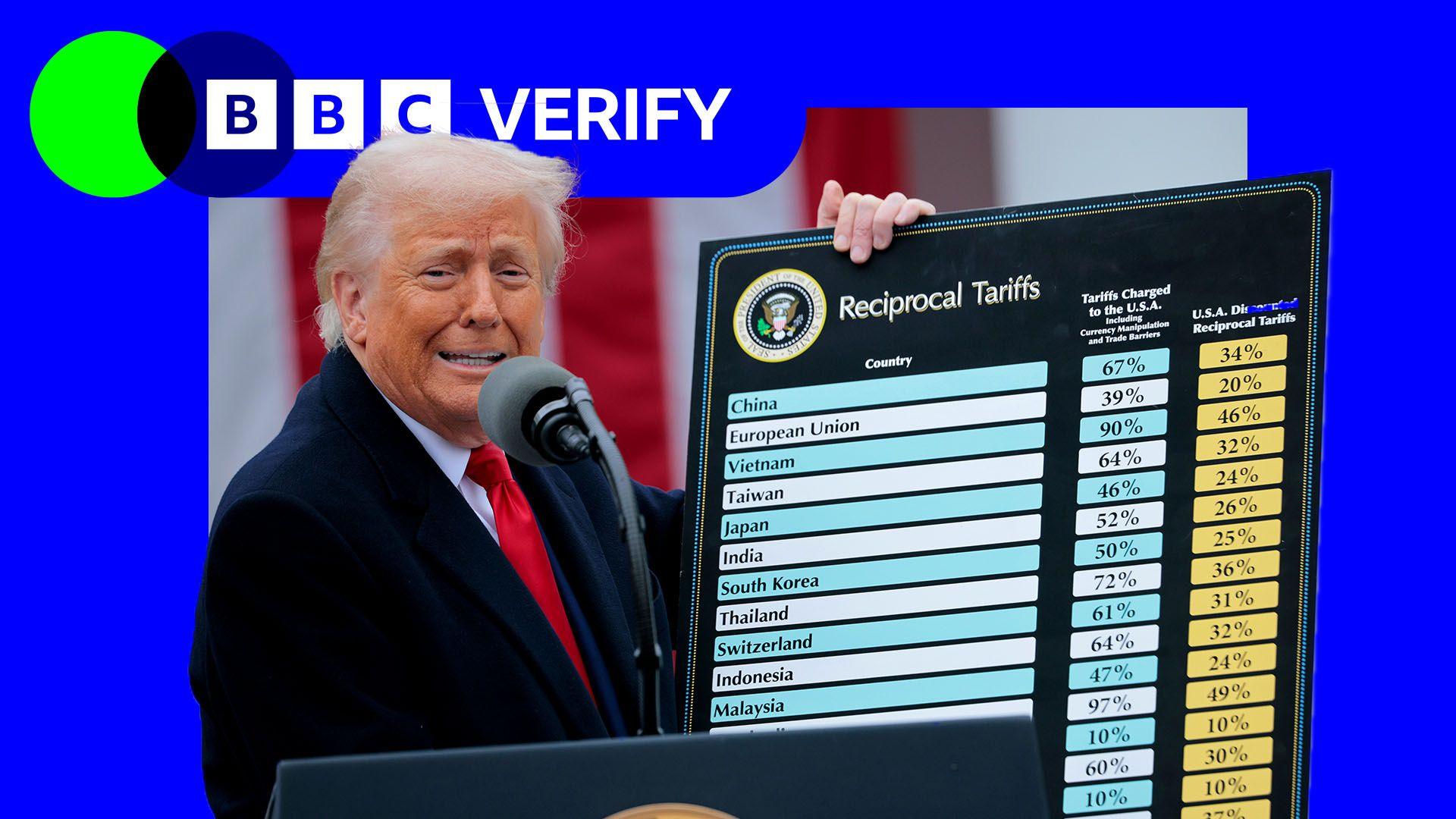

On 7 August, his sweeping new tariffs - taxes on imports - on more than 90 countries came into effect.

They range from 10% on the UK to 41% on Syria and India is facing a 50% tariff rate.

They take America's average effective tariff on the outside world to its highest level in almost a century.

Specific commodities and goods, including automobiles and steel, have also been targeted with significant tariffs by Washington.

The tariffs themselves are ultimately paid by the US companies that bring goods into the country from abroad and their impact is being felt in America and the global economy in different ways.

More tariff revenue for the US government

The Budget Lab at Yale University estimates that, as of 7 August 2025, external, the average effective tariff rate imposed by the US on goods imports stood at 18.6%, the highest since 1933.

That was up from 2.4% in 2024, before Donald Trump returned to office.

That significant increase means the US government's tariff revenues have shot up.

Official US data shows that in June 2025 tariff revenues were $28bn, triple the monthly revenues seen in 2024.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the independent US fiscal watchdog, estimated in June that the increase in tariff revenue, based on the new US tariffs imposed between 6 January and 13 May 2025, would reduce cumulative US government borrowing in the 10 years to 2035 by $2.5 trillion, external.

However, the CBO also judged that the tariffs would shrink the size of the US economy relative to how it would perform without them.

They also project that the additional revenues generated from the tariffs will be more than offset by the revenue lost due to the Trump administration's tax cuts over the next decade, external.

A widening of the US trade deficit

Donald Trump regards bilateral trade deficits as evidence that other countries are taking advantage of the US by selling more goods to America than they buy from it.

One of the justifications for his tariffs is to address that imbalance by curbing imports and forcing other countries to lower their own barriers to US goods.

However, one of the standout impacts of Donald Trump's trade war, so far, has been to increase US goods imports.

This is because US firms stockpiled supplies in advance of tariffs being implemented to avoid being forced to pay the additional tax.

Meanwhile, US exports have seen only a modest increase.

The net result is that the US goods trade deficit has widened, not fallen.

It reached a record $162bn in March 2025, before falling back to $86bn in June.

The distortion caused by stockpiling will fade, but over the longer term many economists expect the Trump administration will still struggle to bring down the overall US trade deficit.

That's because they argue that the deficit is primarily driven by structural imbalances within the US economy - persistent national spending in excess of national production - rather than unfair trade practices, external directed at America by other nations.

China is exporting less to America

Trump imposed punitive tariffs on China, with levies at one stage hitting 145%.

They have come down to 30% but the impact of those trade hostilities on Chinese trade with America has nevertheless been significant.

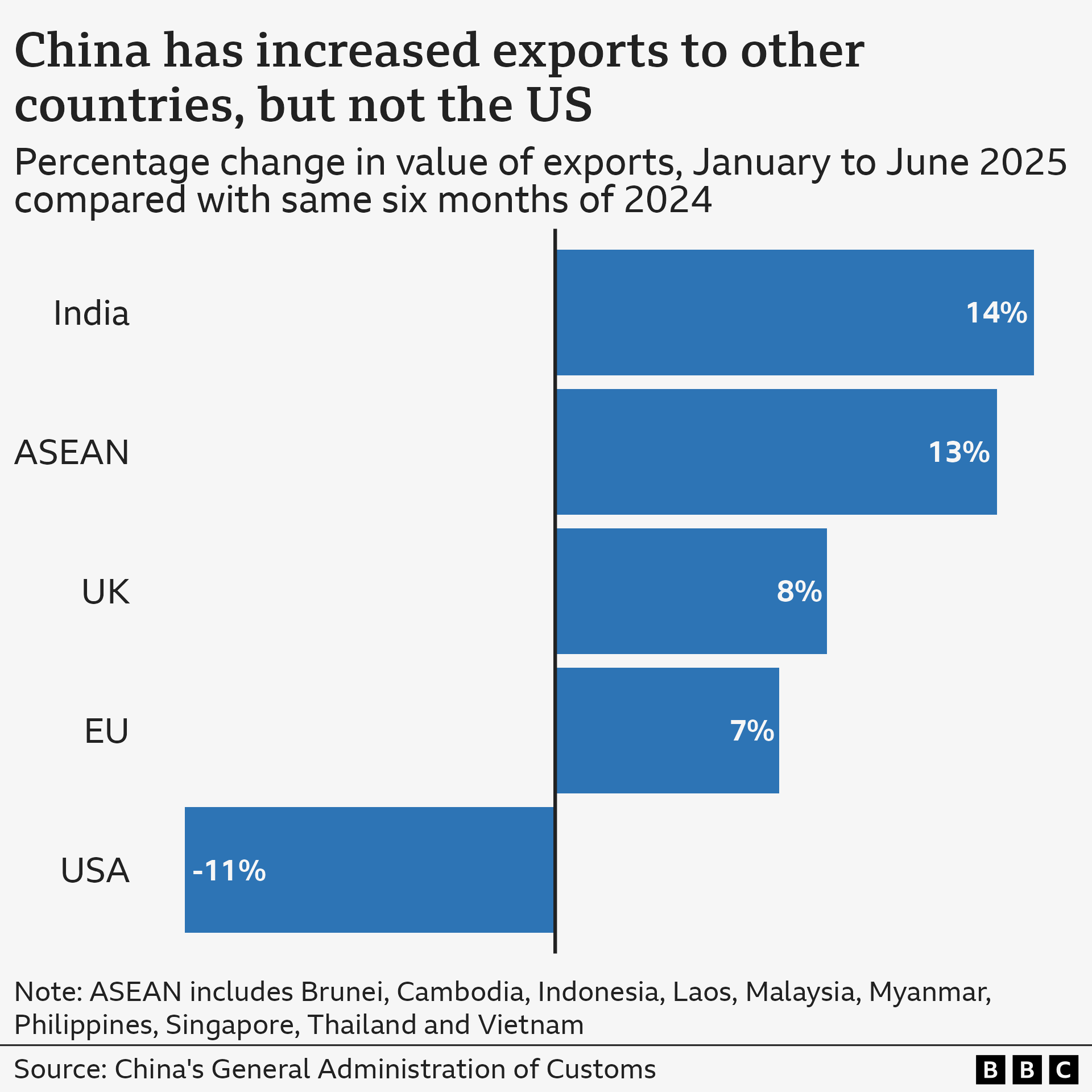

The value of Chinese exports to the US in the first six months of 2025 were down 11% on the same period in 2024.

Meanwhile, Chinese exports to some of its other trading partners have grown, suggesting Chinese firms have been able to find customers in other countries.

China's exports to India this year are up 14% on the same period last year and with the EU and the UK they are up 7% and 8% respectively.

Also notable is a 13% increase in the value of Chinese exports to the ASEAN nations, which include Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia, over that period.

The Trump administration has been concerned about the possibility of Chinese firms attempting to bypass US tariffs on China by setting up operations in neighbouring South East Asian countries - to which they export semi-finished goods - and exporting finished goods to the US from there.

Such "tariff jumping" occurred when Donald Trump imposed tariffs on Chinese solar panels in his first term and some economists argue the increase in Chinese exports to ASEAN nations, external could be related to the same phenomenon.

More trade deals

Some countries have responded to Trump's trade war by seeking to deepen trade ties with other countries, rather than by putting up their own barriers.

The UK and India have signed a trade deal that they were negotiating for three years.

Norway, Iceland, Switzerland and Liechtenstein - who are in a grouping called the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) - have concluded a new trade deal with a number of Latin American countries in a grouping known as Mercosur.

The EU is pushing ahead with a new trade deal with Indonesia.

Canada is exploring a free trade agreement with ASEAN.

Some countries have also taken advantage of the fracturing of trade between the US and China.

China has traditionally been a significant global importer of soybeans from the US, which it uses as fodder for its 440 million pigs.

But in recent years Beijing has been increasingly shifting towards buying its soybeans from Brazil, external, rather than America, a trend analysts argue has accelerated as a result of Donald Trump's latest trade war and Beijing's new retaliatory tariffs on US agricultural imports.

In June 2025 China imported 10.6 million tons of soybeans from Brazil, but only 1.6 million tons from the US.

When China put retaliatory tariffs on US soybean imports in Donald Trump's first term his administration felt the need to directly compensate US farmers with new subsidies.

US consumer prices are starting to rise

Economists warn that Trump's tariffs will ultimately push up US prices by making imports more expensive.

The official US inflation rate for June was 2.7%. That was up slightly from the 2.4% inflation figure for May, but still below the 3% rate in January, external.

Stockpiling in the earlier part of the year has helped retailers absorb the impact of the tariffs without needing to raise retail prices.

However, economists saw in the latest official data some signs that Trump's tariffs are now starting to feed through to US consumer prices.

Certain imported goods such as major appliances, computers, sports equipment, books and toys showed a marked pick up in prices in June.

Researchers at Harvard University's Pricing Lab, who are examining the effects of the 2025 tariff measures in real time using online data from four major US retailers, have found that the price of imported goods into the US and domestic products affected by tariffs have been rising more rapidly in 2025, external than domestic goods that are not affected by tariffs.

Additional reporting by Alison Benjamin, Yi Ma, Anthony Myers.

Follow BBC's coverage of US tariffs

LIVE UPDATES: Follow the latest updates and analysis

EXPLAINER: What tariffs has Trump announced and why?

CONSUMERS: Six things that will get more expensive for Americans