Hinkley: Why do we need the new nuclear power station?

- Published

- comments

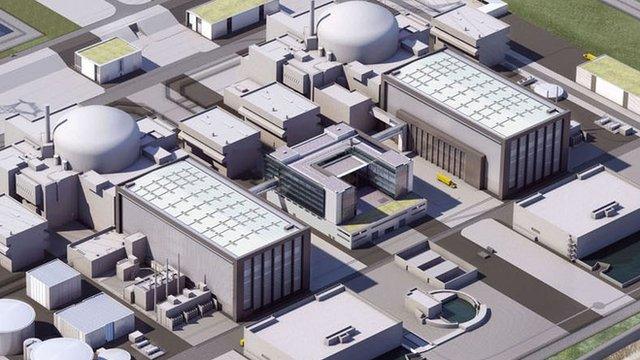

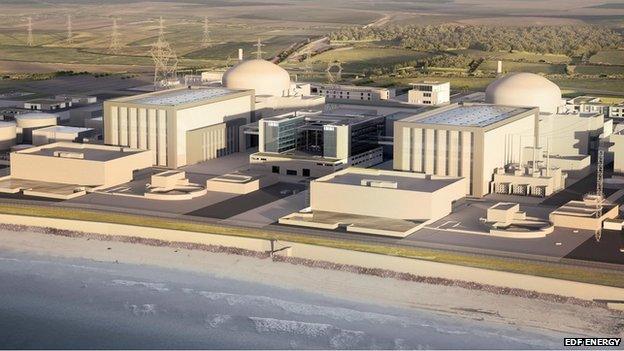

The site of the planned Hinkley Point C nuclear power station in Somerset

Why is a new nuclear power station at Hinkley Point running years behind schedule and the cause of seemingly endless debate? Here are some answers to the questions surrounding the world's most expensive power project.

What is the Hinkley Point project?

Hinkley Point C in Somerset was supposed to be the first of a new batch of nuclear power stations that then prime minister Gordon Brown announced in 2008. The plan was to build two 1,650-megawatt nuclear reactors, with an anticipated life span of 60 years - among the biggest in the world - at the site as part of the UK's energy security strategy.

The £18bn project plans to use new technology that is not yet in use anywhere else and is being built by France's EDF, with some funding from a Chinese government-controlled firm.

The site - already home to the disused Hinkley Point A and the still-operational Hinkley Point B - remains largely undeveloped despite plans for it to be operating by 2017.

Why do we need it?

New nuclear stations such as Hinkley Point would reduce the UK's reliance on imported gas, as North Sea production continues to fall. Gas and coal-fired power stations still produce about half the country's electricity. It's designed to meet 7% of the country's total energy needs.

The UK's existing nuclear plants - such as Hinkley Point B, which was connected to the grid in 1976 - are nearing the end of their working lives. In addition, the UK's remaining coal-fired power plants are expected to close by 2025 to meet new EU air quality rules. That will create a big gap in generating capacity that must be filled if the lights are to stay on.

The Hinkley Point B nuclear plant (left) began producing electricity in 1976

Why is it being built with French and Chinese money?

EDF - France's state-controlled electricity company - bought British Energy, which owned the UK's nuclear power stations, in 2008.

Hinkley C was already planned but when the outline of the plans were announced in October 2013 it was clear the company needed an investment partner to help shoulder the huge cost.

Two years later China's General Nuclear Power Corporation agreed to take a one third stake worth £6bn in the venture.

However, EDF has still not made a full commitment to go ahead with building the Hinkley Point reactors.

Why is EDF hesitating?

The company has debt of more than €37bn (£28bn), its share price has more than halved in the past 12 months and the company is in the process of buying Areva, the company behind new nuclear power plants it is building in Finland and Flamanville, northwestern France which are running late and are significantly over-budget. They are using the same EPR (European pressurised reactor) technology that will be installed at Hinkley Point.

The new reactors are being developed by Areva, another French company which EDF is being compelled to buy by the French government. The delivery date for the new reactors has been pushed back four times over safety concerns and is now not due until late 2018.

EDF's existing nuclear reactor at Flamanville in northwestern France

Malcolm Grimston, an honorary senior research fellow at Imperial College London, says the fact that EDF has still not committed to going ahead with Hinkley Point reflects the concerns the company has about the financial impact of acquiring Areva and the delays in Finland and Flamanville. He says it is still possible that EDF may not decide to go ahead, but that would create big political problems for the French government.

On paper the deal is a good one for EDF, given the "strike price" - that's the price the UK has committed to pay for electricity from Hinkley Point: £92.50 per megawatt hour. That is far higher than the current price of electricity of about £37 per megawatt hour. But nuclear power plants often cost far more than expected and can take far longer to build.

Those financial fears are thought to be behind the resignation of EDF chief financial officer Thomas Piquemal.

Analyst Xavier Caroen, of broker Bryan Garnier, says Mr Piquemal was calling for a three-year delay before EDF made its final investment decision.

But EDF chief executive Jean-Bernard Levy and the French government were both thought to prefer a faster timetable.

Mr Levy said on Monday that a final verdict would be made "in the near future" and some analysts believe Mr Piquemal's departure removes the final barrier.

EDF chief executive Jean-Bernard Levy

Can't Britain just build more wind farms instead?

About a quarter of the UK's electricity now comes from renewable sources such as wind, solar and hydro. The trouble is, as Dr Heather Wyman-Pain of the University of Bath points out, "the wind does not always blow and the sun does not always shine".

That means we still need more traditional forms of generation - particularly given that total demand for electricity in the UK can hit about 60,000 megawatts in the depths of winter. The figure compares with the minimum demand of about 20,000 megawatts, meaning a lot of spare capacity is needed for what can be very short periods of time.

Supporters of renewables argue that if more resources went into researching and developing them, they could still take on a greater role in UK energy provision.

The Scout Moor wind farm in the South Pennines near Rochdale

What difference would Hinkley Point C make to my electricity bill?

In the long run, it would be likely to push up bills given that the government has committed to paying well above the current market rate for the electricity it will generate.

However, the UK needs to build more power stations if it is to meet growing demand for electricity and the government wants to ensure consumers foot the bill no matter where the electricity comes from.

Dr Wyman likens nuclear to a kind of fixed-rate mortgage. Electricity from Hinkley Point might look expensive today, she says, but she argues it boasts the advantage of being generated within the UK, helping the country become more energy self-sufficient.

- Published21 September 2015

- Published21 September 2015

- Published7 March 2016

- Published27 January 2016

- Published24 September 2015