The nuclear industry: a small revolution

- Published

The BBC's Roger Harrabin explains how small nuclear reactors might work - using bags of rice

Nuclear reactors may be about to shrink before our eyes.

After decades of building giant reactors in domes big enough to swallow a cathedral, nuclear engineers are thinking small.

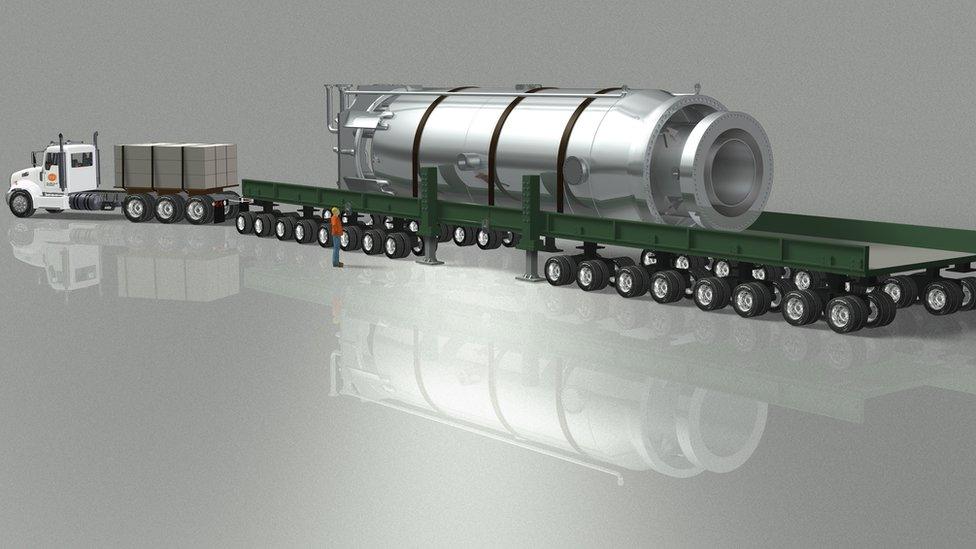

They believe part of the solution to the energy crisis will come from factory-built mini-reactors, just 23m (75ft) long, delivered to the site on the back of a lorry.

Fans of small modular reactors (SMRs) say they will avoid the problems of delay and cost over-run that has beset traditional reactors.

Most importantly, they say, "mini-nukes" as small as a tenth the size of a conventional reactor would be much easier to finance.

Financial concerns

Finance has become the biggest obstacle to new nuclear plants.

The UK is locked in nuclear paralysis because EDF hasn't yet confirmed the funding for the planned Hinkley C nuclear power plant - despite the backing of two of the world's richest governments, France and China.

Footloose investors scanning the world for money-making opportunities tend to turn away when they see a nuclear reactor taking years to build, fraught with technical and political risk.

Nuclear proponents say transportable mini-reactors could be the future for the industry

Solar and wind energy offer much more predictable returns in a fraction of the pay-back time.

But SMR fans say mini-nukes as small as 50 megawatts (MW) could change that. They suggest it's as simple as placing your order and waiting for a reactor to turn up. Then plug and play - and wait to get your money back.

If you want large-scale power, just line up a dozen SMRs side by side. It's a bit more complicated than that, of course, but potential offered by this technology is exciting governments worldwide.

In his most recent Budget, the Chancellor George Osborne announced a competition for the design of small modular reactors for use in the UK.

'Evolutionary technology'

There are two catches.

First, there's still no solution (in the UK at least) to what to do with the nuclear waste. The government appears willing to go ahead with new nukes without knowing what happens to spent fuel and contaminated equipment.

Second, no-one has actually built an SMR yet, and it's likely to take until the 2030s or 2040s before SMRs are widespread and making a real contribution to hitting carbon emission targets.

NuScale hopes to have its first reactors in operation by 2025

The firm claiming to be leading the global SMR race is the US government-funded NuScale. It expects to have its first American SMR in operation by 2025, and hopes to be ready to generate in the UK in 2026 at the earliest.

The veteran nuclear champion Dame Sue Ion believes SMRs will play a vital role in the 2030s and 2040s when transport and home heating will need to be de-carbonised in order to meet the commitments in the UK's Climate Change Act.

"Personally I think SMRs are probably the future of nuclear," she says. "These things can be making a substantial contribution from the early 2030s onwards.

"I'm really confident because it's not new technology - it's evolutionary technology from light water systems that have been around for 50 years.

"We're not doing something brand new - we are just doing it more efficiently and cost-effectively."

Some investors say solar and wind energy offer more predictable returns

The USA, Canada, South Africa, India, Pakistan and Argentina are all interested in SMRs. China has been operating a prototype since 2000. Several firms in the UK are showing interest.

'Jam tomorrow'

However, there are cautionary voices. Experts warn that to make it worthwhile building it, a reactor factory would need 40-70 orders.

Yet given the strength of interest globally that may not be such a huge challenge in a world that's committed to predictable low-carbon energy.

And the time scale is a big stumbling point for many.

According to John Sauven of Greenpeace there's a high risk it will take longer than predicted to bring small scale nuclear on-stream.

"Remember the nuclear industry promised in the 1950s that it would deliver energy too cheap to meter," he says.

"Since then it's been completely overtaken by wind and solar energy which are much safer, reliable and cheaper.

"With nuclear it's always jam tomorrow. We've got to decarbonise the energy industry now."

Other critics warn that renewables and energy storage are progressing so fast that the energy industry won't need the sort of round the clock "baseload" power produced by nuclear in the medium term future.

The energy commentator Kees van der Leun tweeted: "By the time [of the 2030s and 2040s] the growth of cheap solar and wind will have obliterated the chance of making any money with 'baseload'."

Follow Roger on Twitter @rharrabin