Tata Steel UK: What are the options?

- Published

Port Talbot. What are the options?

With Tata abandoning its UK operations, the future for British steelmaking is bleak.

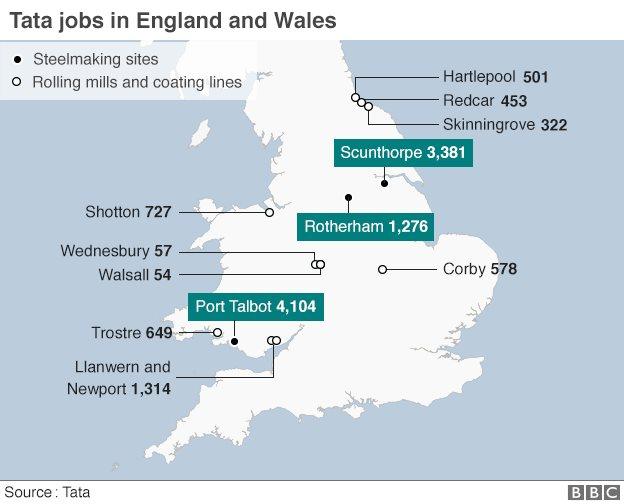

Tata Steel UK has operations in Port Talbot, Trostre, Shotton, Llanwern and Newport in Wales and Rotherham and Corby in England.

Here we look at the options for the industry.

Sale

This is the preferred outcome for everyone - if a buyer can be found.

Business Secretary Sajid Javid has said: "There are buyers out there", but no realistic candidate has put themselves forward.

It is hardly surprising. Tata invested £3bn into its UK operations and is still losing £1m a day as steel prices continue to fall.

Liberty House who are buying Tata's Lanarkshire plants have told the BBC that they are being "very cautious". It is actively looking for steel assets but largely in the "downstream" market - the manufacturing of steel products rather than the steel itself.

Greybull Capital, which specialises in turning around underperforming businesses is negotiating with Tata over the Scunthorpe works.

But Tata Steel UK is on a different scale. Greybull is considering a £400m investment in Scunthorpe, in contrast to the £2bn or more that is thought to be needed to restructure Tata Steel UK.

Nationalisation

Even a temporary nationalisation of Tata Steel UK by a Conservative government would be astonishing. It seems an unlikely scenario.

Mr Cameron said on Thursday: "We are not ruling anything out. I don't believe nationalisation is the right answer."

Supporters of the idea say that that is precisely what the Labour government did during the financial crisis when it bailed out the banking system. Indeed Royal Bank of Scotland is still majority (58%) owned by the government.

Rules on the steel industry are fundamental to the European Union, dating back to the Treaty of Rome in 1957, but they do not prohibit nationalisation.

Under the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Article 456, external says: "The Treaties shall in no way prejudice the rules in Member States governing the system of property ownership".

The Article is usually seen as a way of facilitating privatisation, but could well be used to allow nationalisation as well.

Even so the government would have to convince the Commission that it is acting as a private investor, putting money in to increase profitability - not simply subsidising a loss-making business.

Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon visits Lanark steel mills which were, very briefly, nationalised.

Temporary nationalisation

If faced with immediate closure there might be an option for the government to temporarily take ownership before selling it on.

Ministers have been unable to secure a promise from Tata over how long they will allow the plants to remain open.

The Scottish government temporarily nationalised Tata's Lanarkshire mills during the sale to Liberty, although ownership lasted only a matter of minutes, and was done for technical reasons at no cost to the tax payer.

Nationalisation of the business for the short-term might be politically more acceptable, but the government would have to absorb all the costs.

It would also run into problems with EU rules on state aid.

The government was allowed to step in and help the banking system during the 2008 crisis because its failure threatened the economic security of the country.

The same cannot be said of the steel industry.

Government support

There are other ways the government might support the steel business if no buyer comes forward soon.

One option being considered by ministers is to "mothball" the blast furnace at Port Talbot.

It is thought this would cost between £10m-£20m a month and would also involve laying off most of the workforce.

Another option, thought to have been part of a package put to the Tata board earlier this week, involves a buy-out by managers and staff at Port Talbot.

While Tata called the plan "unaffordable" it might work with the help of government loans or loan guarantees, similar to the ones being considered in the sale of Scunthorpe to Greybull.

Again the EU rules restrict what the government can do to help.

Ilva steel plant in Italy where the European Commission is investigating whether it's receiving illegal state aid

The European Commission in the past has ordered the recovery of illegal state aid in the steel industry from Belgium, Germany, Italy and Poland.

For instance, the Commission is investigating Italy's third largest steelmaker Ilva, which was given €2bn in government support supposedly to help it comply with emissions and environmental standards. Rivals claim the money is being illegally used to modernise its plant and increase capacity.

The European Commission told the BBC: "EU rules do not allow rescue or restructuring aid such as emergency loans or government guarantees on loans to steel manufacturers in financial difficulties.

"This is because of past experience and taking into account the features of the EU steel industry, in particular its overcapacity."

Closure

This is the option no one wants, and which everyone fears.

The knock-on effects of a closure would be considerable. The IPPR think tank has estimated that while 15,000 jobs at Tata UK would go there are another 25,000 in the supply chain that would also be at risk, although it says that some of these are not in the UK.

The impact on the Port Talbot area where Tata Steel UK employs some 5,500 workers would be disastrous.

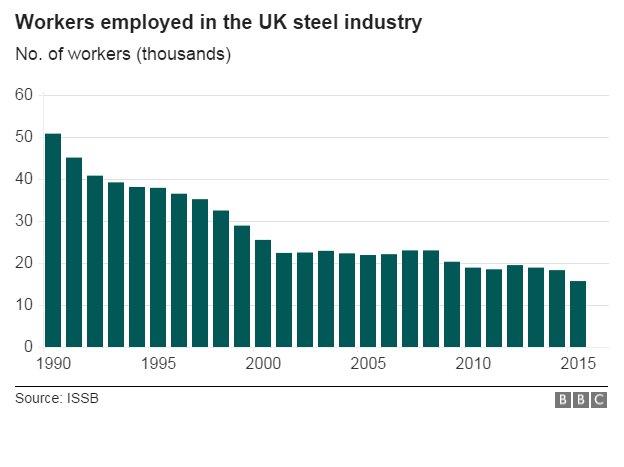

It would come on top of a steady flow of steel job losses: Redcar steel plant, owned by Thai company SSI, closed last year taking with it 1,700 jobs. Port Talbot itself announced 1,000 job losses in January.

- Published30 March 2016

- Published30 March 2016

- Published31 March 2016