Panama Papers: 10 things we've learned

- Published

A huge leak of confidential documents has revealed how the rich and powerful use tax havens to hide their wealth

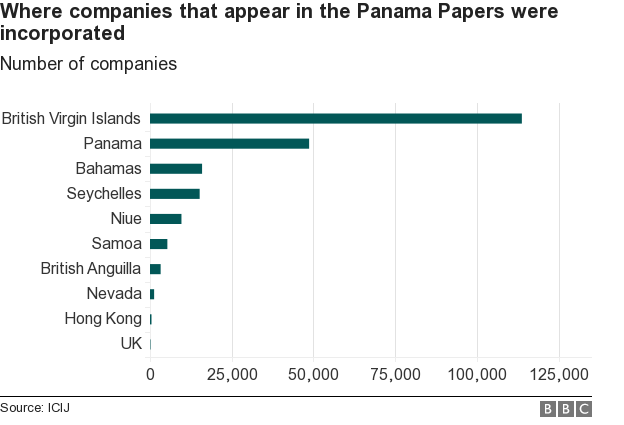

The leak of 11.5 million documents from one of the world's most secret companies, Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca, has grabbed headlines around the world. So what have we actually learned from the Panama Papers?

1. It does what it says on the tin

A tax haven is a tax haven. This may sound simple but, although there were always lots of accusations that so-called Offshore Financial Centres were little more than places where the rich, corrupt and criminal could hide their ill-gotten gains, the proof was not always there.

The countries themselves talk about their "specialist financial expertise" and "tax planning" abilities, while their critics say that this was being used as a front for crime on a massive scale. The sheer size of the release of documents from Mossack Fonseca has enabled us all to see numerous examples of just what has been going on. We always suspected it was a can of worms - now the lid has been lifted and we know for certain that it is.

2. Everybody needs friends they can trust

Close friends Sergei Roldugin and Vladimir Putin, pictured in 2009

None of the money that seems to have flowed from Russia into tax havens belongs to President Putin, but billions of dollars of it seems to belong to his friends. For the Kremlin, this is a sign that the revelations are driven by Putinphobia and those determined to do down Russia. For most other people it looks like the president is using his trusted friends to launder money for him.

You can take your pick but if you think that this is a conspiracy against President Putin, you might have to explain why one of his best friends, a Russian classical cellist, has made quite so much money.

3. Iceland is more interesting than we thought

Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson yielded to the pressure on him to resign

For all its beauty and the famous collapse of its banking system the assumption up until now has been that Iceland, like its Scandinavian cousins, is one of the good guys - honest, decent and trustworthy.

But the Icelandic prime minister has had to resign over accusations he hid millions of dollars in a company in the British Virgin Islands - a company that had a direct interest in the health and wealth of Iceland's banks - which as prime minister he was responsible for. Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson has insisted he and his wife have followed Icelandic law and have paid all their taxes in Iceland but that is not really the point, not when your country was brought to its knees by a banking crisis.

4. Common or garden criminals' money is as good as anyone else's

How do the papers link to the 1983 Brink's Mat robbery? Richard Bilton reports

While much of the focus has been into the dealings of dictators and corrupt regimes around the world, it seems that Panama is not above helping good old-fashioned robbers. For it is also alleged that Mossack Fonseca helped launder the millions stolen during the notorious Brink's Mat gold bullion robbery of 1983, when three and a half tonnes of gold disappeared.

Allegedly the Panamanian company tried to stop the British police from tracking down that cash, by setting up a company for a property dealer called Gordon Parry. Even though it knew Mr Parry was laundering money from the Brink's Mat robbery, it even even helped him regain control of the stolen money when the police were drawing near. Mr Parry was finally caught in 1990 and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

5. There is still a great deal of explaining to do

Rami Makhlouf is Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's cousin; HSBC denies any wrongdoing

Some of the leaked files from Mossack Fonseca show it enabled a leading regime figure in Syria, Rami Makhlouf, to keep his companies trading, despite being blacklisted by US Treasury sanctions and UK sanctions. The papers also show the Foreign Office in the UK was aware of one of those companies.

In 2011, after sanctions on Mr Makhlouf were in place, HSBC - one of Britain's largest banks - asked the governor of the British Virgin Islands for a certificate of incumbency for Drex Technologies, one of the businesses owned by Mr Makhlouf. That certificate is basically an identity check.

In order to get it approved, the governor of the British Virgin Islands needed to get it signed by an official at the Foreign Office on behalf of the foreign secretary. The document very clearly states that the director of Drex Technologies is Rami Makhlouf. The document is stamped and signed by a Foreign Office official.

HSBC has denied any wrongdoing. It says that it works closely with the authorities to fight financial crime and implement sanctions.

6. The tax man cometh

The list of countries that are interested in examining the 11.5 million documents continues to grow. Germany, Norway, France, Spain and Australia are just a few of those that have promised to examine how many of their citizens have been using the company and if they have been evading tax illegally. The German authorities, who had an advance leak of some of these papers, have already been raiding homes and businesses looking for evidence.

There was a surge in business for Mossack Fonseca when the European Savings Directive made hiding your money in Europe more difficult. With many people looking to hide "black" money, there must be a lot of nervous tax dodgers out there.

7. Some people know less than we do

Family members of China's president have been named in the leaked documents

Strangely enough it is rather difficult to research parts of the Panama story online in China, especially the allegation that close relatives of seven current or former Chinese leaders have been found to have links to offshore firms. Documents leaked from Panama name family members of Chinese President Xi Jinping and two other members of China's elite Standing Committee, Zhang Gaoli and Liu Yunshan.

8. Do they play footie in Panama?

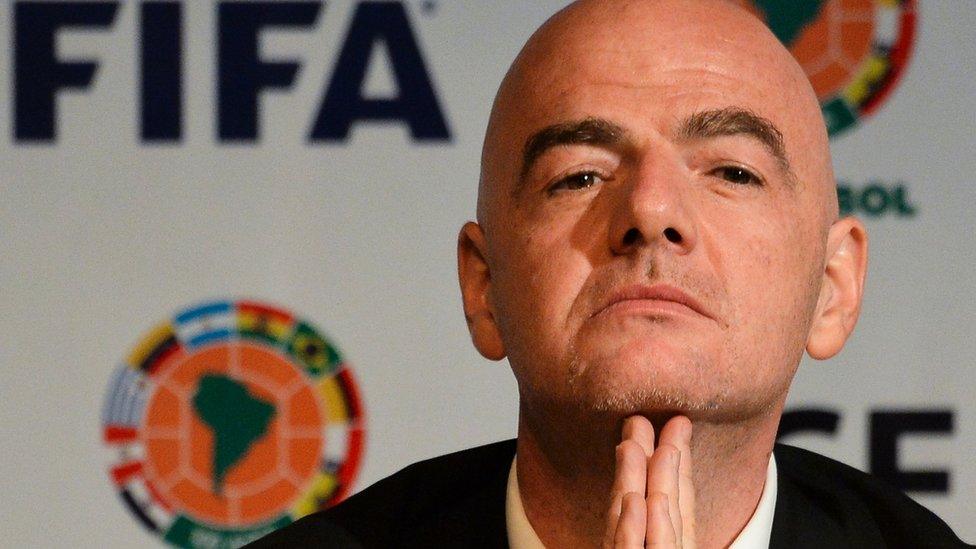

Infantino insists he "never personally dealt with Cross Trading nor their owners"

Fifa president Gianni Infantino has denied wrongdoing after leaked documents suggested he signed off on a contract with two businessmen who have since been accused of bribery.

Hugo and Mariano Jinkis own a company called Cross Trading and bought TV rights for Uefa Champions League football, which they immediately sold on for almost three times the price. The 2006 contract was signed off by Infantino when he was a Uefa director. Infantino says he is "dismayed" that his "integrity is being doubted".

Cross Trading also has links to Juan Pedro Damiani, a member of Fifa's ethics committee who has already been placed under internal investigation

9. Offshore firms are helping push up London house prices

Buying a property in central London is out of reach for many British people

The leak of papers from the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca shows how many of the most expensive properties in London are owned by foreigners through offshore companies that hide their identities.

House prices in much of the UK are already at eye-watering highs but in the centre of London they are at a different level. While some British people can afford those prices, many properties are bought by foreigners.

The attraction is obvious: London is a safe and attractive city and every time there is a crisis somewhere in the world, another swathe of worried wealthy locals decide to put some of their money in London. That forces up the price of property in central London and that ripples out across the capital and then the country.

London mortgages could be so large in part because of the ease with which Middle Eastern royal families, Russian billionaires and the political leaders of corrupt regimes can use secret offshore companies to hide their identities and how much property wealth they have in London.

10. This is just the start

The list of allegations continues to grow and the scale of the issues involved is also on the rise - from corrupt officials and regimes, to money laundering, to tax evasion and sanctions busting. So far we have read only a small percentage of the total number of documents. The accusations are likely to keep on coming and the pressure on governments to do something is bound to continue, if only to show that it is not just the little people who pay taxes.

Panama Papers - tax havens of the rich and powerful exposed

A total of 11 million documents held by the Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca have been passed to German newspaper Sueddeutsche Zeitung, which then shared them with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, external. BBC Panorama is among 107 media organisations - including UK newspaper the Guardian, external - in 76 countries which have been analysing the documents. The BBC does not know the identity of the source

They show how the company has helped clients launder money, dodge sanctions and evade tax

Mossack Fonseca says it has operated beyond reproach for 40 years and never been accused or charged with criminal wrong-doing

Tricks of the trade: How assets are hidden and taxes evaded

Panama Papers: Full coverage; follow reaction on Twitter using #PanamaPapers; in the BBC News app, follow the tag "Panama Papers"

Watch Panorama on the BBC iPlayer (UK viewers only)