'I want to train more water warriors'

- Published

The entrepreneurs aiming to provide clean water to all

Water may make up 70% of the world, yet for 783 million people, access to clean water is something they just don't have.

Drinking and bathing in dirty water can be fatal but there are those who have decided now is the time to use simple solutions to change the situation.

In India, Matthew Wheeler and Priti Gupta paid a visit to the country's famous "Water Doctor", while Zoe Flood found out how entrepreneurs in East Africa are helping their communities access clean water.

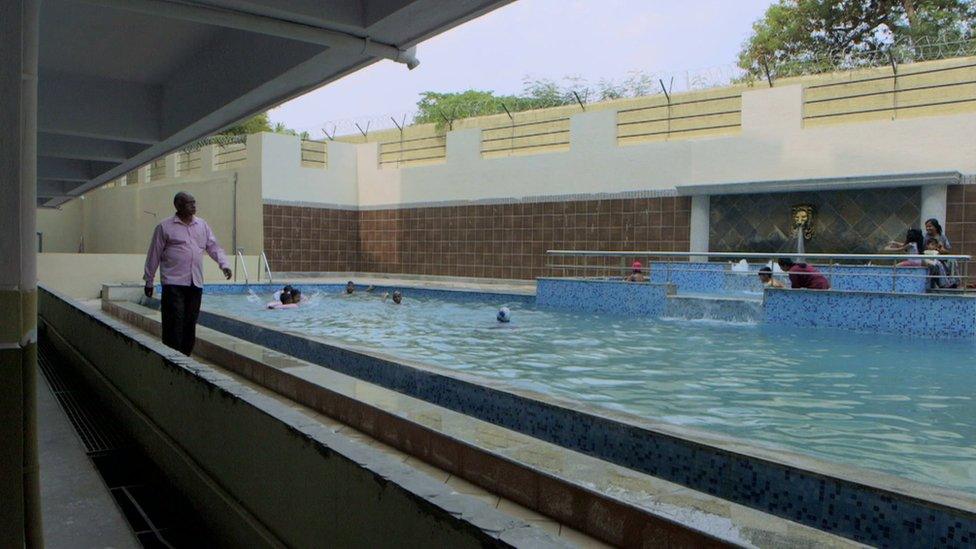

Ayyappa Masagi is passionate about spreading the word about creating safe water

The Water Doctor, Andhra Pradesh, India

Ayyappa Masagi has a simple message: "You want water? Call me!" Thousands have. And his phone rings dozens of times a day. There appears to be an endless supply of patients for the man nicknamed India's "Water Doctor".

"I faced a lot of water problems in my childhood," he says. "I used to go at 3am to fetch water from the stream. So I made an oath that when I grew up I would find a solution. So I quit my job as a mechanical engineer in 2002 to solve India's water problem."

India is enduring a catastrophic water crisis. About 330 million people are suffering water shortages after the failure of the last two monsoons. Reservoirs are dry. Farmers have committed suicide. Thousands of drought-stricken villagers have flocked to cities, desperate for water, praying for rain.

According to Mr Masagi's calculations, if just 30% of India's rainwater were captured and stored, "one year's rain would sustain the nation for three years."

Big plans

Mr Masagi thinks the community's attitude towards water needs to change

To prove it, in 2014 he bought 84 acres of barren land near Chilamathur, a famously drought-prone region of Andhra Pradesh, 110km northeast of Bangalore. "The wind here was like a firewind. I told my partners, 'Within one year I will make this land a water bowl.'"

Today, a network of 25,000 sand-filled pits and four new lakes capture and store any rainwater that falls here. No drop is allowed to escape into rivers and run off to the sea. It stays on and in the land, keeping the subsoil charged with water which, when needed, is drawn from five shallow bore-wells.

The topsoil from digging out the lakes has helped level the land, which has been planted with trees and crops. Roughly 60% of the trees will form dense forest, while 40% will be fruit trees to generate income. Grains and vegetables have also been planted, and next year there will be a dairy here too. The plan is to make this a sustainable organic farm, totally self-sufficient for all its water needs.

Through his Water Literacy Foundation, Mr Masagi is training "water warriors" to spread his message. He's already written seven books and trained more than 100 interns from India and abroad, including Germany, Japan and the US.

"If you only talk, nothing will happen. You have to do something and prove it. Governments are coming forward to take up my service, replicating my model. Once the community attitude changes, our political attitudes change, we can replicate this concept throughout the world."

Changing the Rules

How social entrepreneurs are tackling the world's problems

Jibu, Nansana, Uganda

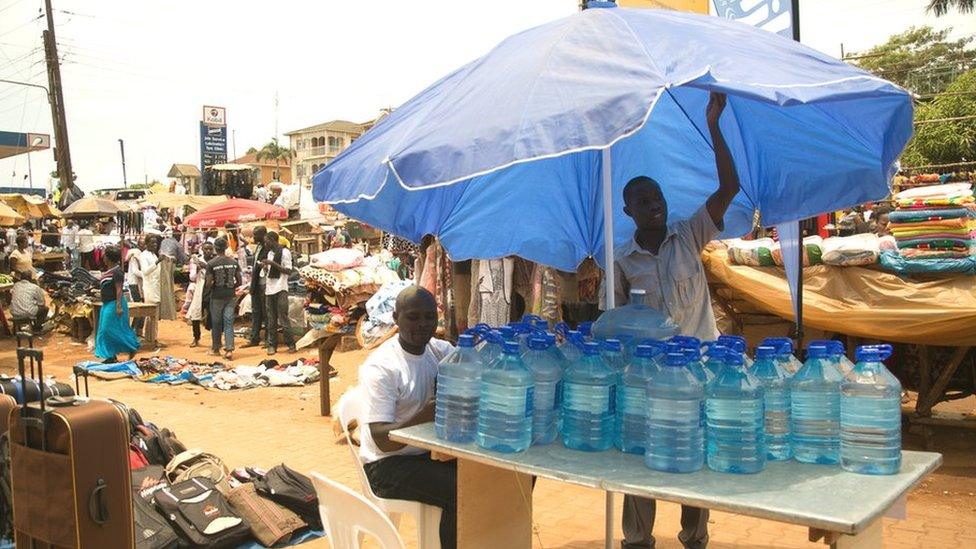

The Jibu model in practice at Kamwoyka market in Kampala

Curious passers-by stop in at a tent outside Belinda Nagawa's franchise in Nansana, Kampala to sip cups of Jibu water, filtered in an advanced mini-water treatment plant installed on site.

"I was working with another franchise as a manager," says the 21-year-old. "I had to get more involved myself in order to become a franchise owner."

Galen Welsch, CEO of the organisation, explains: "The franchisees come to us and they co-invest a licensing fee.

"Then we invest in the full build-out of the franchise, which is a production room and a high-visibility retail space. As they sell water, we charge them per litre they sell and that is how we recover the capital expenditure that we invested in the franchise launch."

The business targets people who previously boiled their drinking water, by offering a cost-effective and safe alternative that is produced on location.

The bottles are all reusable

Various bottle sizes line the shelves of Belinda Nagawa's new shop - Jibu distributes water in reusable bottles for which customers put down a small deposit.

"Most people take water from the tap and then boil it," says Mr Welsch. "The cost of boiling when you pay for charcoal or gas or electricity is actually quite high and boiling doesn't remove any sort of contaminants in the water."

Learning curves

Jibu piloted its model in Uganda, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, but has since worked to launch in Kenya after the DR Congo pilot failed.

"We've gone from two franchises that were fully functional at the beginning of 2015 to 22 today, and then about 15 microfranchises and subfranchisees. These are a pipeline for new franchises," says Mr Welsch.

"Our top-performing franchises are selling more than 5,000 litres a day and generating revenues of $120,000-$140,000 (£83,000-£97,000) a year - the margin they work on is 20-30%."

Microfranchises operate as resellers or points of sale for the main franchises and also give both the entrepreneurs and Jibu the chance to test each other out.

"Someone who is interested in working with us has to first own an outlet where the model involves buying water from an existing franchise and then resell it in their community," explains Daphne Tashobya, lead controller of Jibu Uganda.

"You don't do the water filtration right away - you test yourself to see if you are really interested in the business and you also start learning a few things such as how to keep your books."

- Published10 June 2016

- Published3 June 2016

- Published27 May 2016

- Published13 May 2016

- Published6 May 2016