'I will keep working until I can't any more'

- Published

'I don't want to sit idle and just gossip'

There's no such thing as retirement any more for millions of elderly workers around the world.

Longer life expectancies combined with higher living costs means working until you physically can't is a reality for many.

However, that also means there's a trend emerging for a post-retirement career.

Juliana Liu visited a Hong Kong restaurant where the hiring policy emphasises life experience over other skills, while Matthew Wheeler and Priti Gupta picked up some tips from the knitting grandmothers of Bangalore in India.

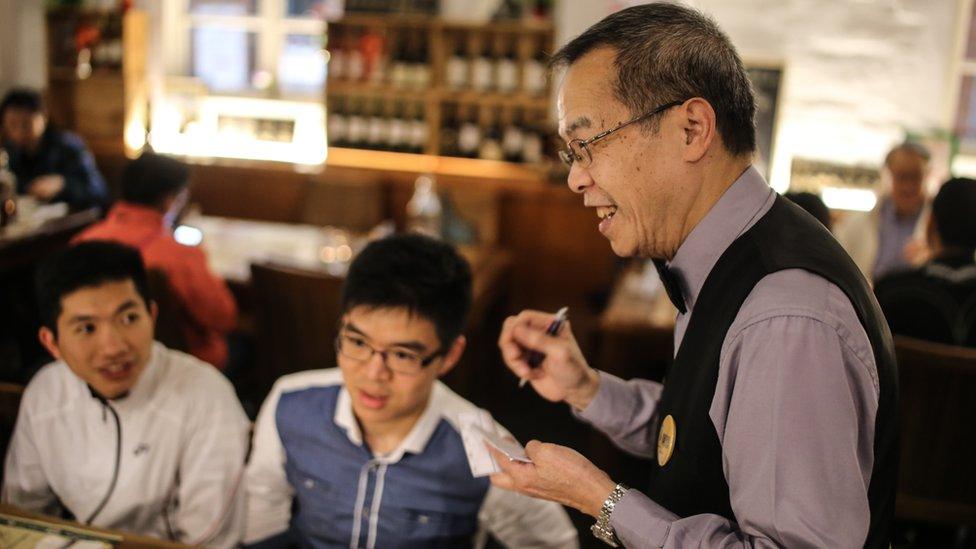

Gingko House, Hong Kong

Gingko has employed more than 1,000 elderly people over the past decade

When Choi Chor Tung approached his 65th birthday, he applied for a job at Gingko House, a Hong Kong social enterprise that mainly hires elderly workers at its four restaurants and the organic farm it uses to supply its eateries.

Mr Choi, who was at that point a butcher, wanted to join Gingko as he was afraid of being fired from his previous job because of his age.

"If you want to retire, then you have to have a lot of savings. But most people in Hong Kong don't have a lot of savings or pension money. It goes very quickly," he says. "Only a place like this will employ someone of my age. I'm 66. I will keep working until I can't work any more."

Now he is a full-time kitchen worker making salads and pizza at Gingko's flagship restaurant, which serves both Chinese and Western food.

Unequal lives

In Hong Kong, the sight of wizened, weather-beaten men and women bending over rubbish bins to collect scraps for sale is all too familiar. They are part of a dark secret: this city is one of the world's most unequal places in terms of income distribution.

About one in five of its seven million people live in poverty, according to government figures. Among the elderly, one in three lives below the poverty line. In fact, the most recent official data suggests the poverty rate among people over 65 years of age has risen by 19% between 2009 and 2014.

City officials believe the best way to reduce poverty is to expand economic growth and create jobs but elderly people say age-related discrimination is pervasive.

That's why Joyce Mak, a former social worker, started the social enterprise 10 years ago.

Gingko House serves international cuisine

She had no experience in the restaurant business but wanted to provide a sustainable way of employing senior citizens for as long as they were willing to work.

Since then, Gingko has employed more than 1,000 elderly people.

Granny's Love India, Bangalore

The grannies are using social media to contact people interested in their knitwear

Bangalore is one of the world's major tech cities. It is India's IT hub. And, thanks to Lima Das and her team of industrious grannies, it is now India's knitting hub too.

In 2011, Lima set up grannysloveindia.com, a website that sells children's clothes knitted by grandmothers. It's an idea that has enabled women "in the second innings of their life" to find new purpose and make new friends.

Social media savvy

"I had no clue it would reach a stage like this where people accept it, love the social cause of it," Lima says, sitting in her Bangalore apartment surrounded by stacks of wool.

"It's been great to be part of such a change. The grannies have now become more confident. They have become a part of my life and I have become a part of their life, empowering them and making them realise that they can become entrepreneurs at any stage of their life."

Lima, a textile design graduate, got the idea for Granny's Love when she saw her mother-in-law knitting. "I thought if I give her design directions she can come up with something fabulous."

The business relies on a combination of new technology (the internet and social media apps) and good old-fashioned craft (knitting nans). All orders from the website arrive in Lima's email inbox.

She then creates the design, identifies the granny best suited to knit it, and sends the wool and the design to that granny. "Then, after a week, [the granny] sends back the product, other details are added, and it's packed together with a photo of the granny who made it, and posted to the customer," says Lima.

Another satisfied customer

Getting the customers wasn't a problem. The challenge was to find the grannies and persuade them that knitting was a moneymaking skill.

"I would ask any granny I would meet, 'Do you knit? Do you know this craft?' My biggest challenge was to motivate them. They simply made garments for their families. For them money was not in their mind."

The orders have rolled in, along with a regular flow of positive feedback from customers. And with the grannies becoming more confident with using modern technology, such as Facebook and Snapchat, they are now getting that feedback directly.

Changing the Rules

How social entrepreneurs are tackling the world's problems

"The grannies are now more proactive when it comes to getting an order. They talk to the customers, they come with me to exhibitions."

Lima now has 25 grannies working with her all across India. Shanti Nagpal is one of the recent recruits. "Today I have courage to believe in myself," she says, pausing between stitches on her latest garment. "When I see our knitting creations worn by the children and looking so beautiful, it makes me feel proud."

Suman Prakash, Lima's longest serving knitting nan, finds the work relaxing and spends much of her earnings on more wool so she can knit more clothes for her family. "It's giving me purpose. I don't want to sit idle and just gossip."

- Published10 June 2016

- Published27 May 2016

- Published20 May 2016

- Published13 May 2016

- Published6 May 2016