Will Greek debt deal really change anything?

- Published

Greece's Finance Minister, Euclid Tsakalotos (L), was locked in talks with his eurozone counterparts into the early hours of Wednesday morning

Greece has got some debt relief from the eurozone. Or has it?

It was one of the key items discussed by eurozone finance ministers at a meeting in Brussels

They agreed, external what they called "a package of debt measures".

It's worth spelling out straight away one thing that was not included and was never on offer. There will be no reduction in the amount that Greece ultimately has to repay, what is often called the principal. As the ministers' statement put it: "nominal haircuts are excluded". There will be no debt cancellation.

So the measures they have in mind involve cutting or capping interest rates on the loans and allowing Greece more time to make the repayments.

Some measures are to come into effect this year and next, including a waiver of an interest rate increase that was due in 2017.

For 2018 and after, the eurozone "expects to implement a possible second set of measures following the successful implementation of the programme".

That means that Greece will have to meet the reform commitments set out in the bailout agreement, such as reducing government borrowing needs, labour market reforms and privatisation. If it does then it can expect further similar debt measures.

Greek protesters have continually asked for the country's debt to be written off

Looking even further into the future the eurozone agreed to create what they call a contingency mechanism to be activated if the Greek government's debt situation turns out to be worse than expected.

'Highly concessional' terms

So is this really debt relief at all? Professional investors would say it is. An investor who owns a bond - which is a form of debt, an IOU - would consider it a loss if the repayment term was extended and the interest rate reduced.

The rate on Greece's eurozone debt is already very low - an average of 1.2%, and the repayment period is very long. Currently the final repayment on loans from the eurozone's bailout agency is due in 2059.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) describes the terms even as they are now as "highly concessional".

Dutch Finance Minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem (R) said the ministers had achieved a "major breakthrough"

But it is the IMF that is the key player, arguing that the eurozone needs to go even further in easing the repayment burden.

The IMF did contribute financially to the first two bailouts, but not the current, third one. It has refused because it considers the Greek government debt burden ultimately unsustainable, unless it gets debt relief.

An IMF contribution is not essential for financial reasons. The eurozone can raise the money for the financial markets through its bailout agency, the European Stability Mechanism.

But the IMF's seal of approval would help politically in countries such as Germany, where there is resentment about the idea of rescuing Greece from what many there see as its own financial folly.

'Major climbdown'

So will the new agreement get the IMF on board? The IMF's director for Europe, Poul Thomsen, welcomed the fact that it's recognised that Greek debt is unsustainable and that debt relief is needed.

The IMF is now talking seriously about the possibility of contributing financially to the bailout. But it will want more detail from the eurozone about the debt relief and will make its own assessment of whether the measures are sufficient.

Poul Thomsen hinted that the IMF could now lend to Greece

It will, however, be a decision for the IMF's board, which is made up of representatives of the member countries and some (notably in Latin America) have been unhappy about the IMF's contribution to the previous Greek bailouts.

And IMF staff have already been criticised for softening their position on debt relief.

Sarah-Jayne Clifton, director of the UK-based charity Jubilee Debt Campaign, said: "IMF staff are proposing to lend more money to Greece without the upfront and unconditional debt relief they called for. This is a major climbdown, which once again breaks the IMF's own rules not to lend when they know a debt cannot be paid."

Jubilee's view is that what Greece really needs is significant cancellation of its debts now, or those "nominal haircuts" that the eurozone have repeatedly said are not on the table.

Politically contentious

They are not on the table partly for political reasons. It's a more obvious handout than cutting interest rates or extending the repayment period and so is politically more difficult for countries - notably Germany - where the bailouts are already contentious.

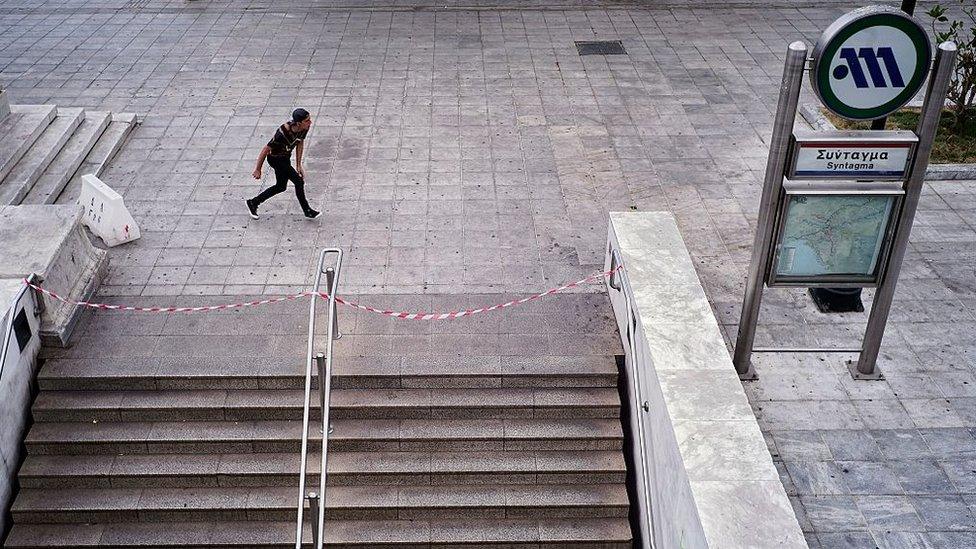

Metro stations were closed in a nationwide strike on 6 May, held in protest at the austerity measures imposed on the country

In addition the eurozone wants as far as possible to give Greece an incentive to make the policy reforms that it has agreed to. That reinforces the reluctance to agree to upfront debt cancellation.

This agreement does represent a significant step in the relationship between Greece and the rest of the eurozone. It certainly is possible to ease a debt burden without "nominal haircuts".

But the agreement is short on specific financial numbers which will need to be filled in. And much will depend on whether Greece can convince the eurozone and the IMF it has made the economic reforms it promised.

That has been a persistent source of conflict between Greece and its creditors. The credit rating agency Moody's said what it called the "implementation risks" are high. Still, it welcomed the deal, describing it as a "road map to debt relief".

Those words recall a cliche that has often been applied to agreements in the Greek story. There is certainly an element in this deal of "kicking the can down the road".