Working Indian women: 'I had to elbow my way into conversations'

- Published

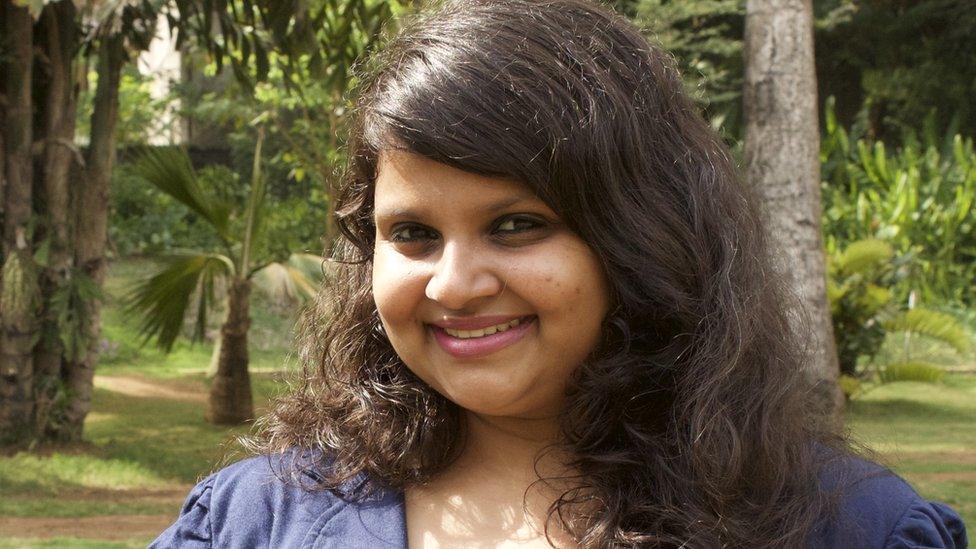

"Women are not taken seriously at work," says Suruchi Sharma

Twenty-four-year-old Aswathi Nair graduated from a marketing course two years ago and now works at a software company. Every time she attends family events there's a question she is always asked.

"Why aren't you getting married? What's the problem?"

The problem is that for a woman in India getting married is often tantamount to turning your back on a career.

Several of Ms Nair's female colleagues have had to leave their jobs, either because they had to relocate to be with their husbands, or because they were expected to prioritise looking after their homes once they were married.

Ms Nair is determined to focus on her career: and in that she is swimming against the tide.

Aswathi Nair says she wants to focus on her career

Fewer than one in four Indian women have paid jobs. In urban areas, the rate is even lower, at just 16%.

Outsourcing change

But there are indications that the tide might slowly be turning.

"One of the key drivers of change is the outsourcing industry," says Vaishali Kasture, an investment banker who also mentors female entrepreneurs.

"It has put good quality jobs for the average graduate up for grabs. We see women who earlier did not have access to jobs, by being just a graduate, now entering the workforce, giving them the economic independence that they needed."

This means that more Indian women are crossing the first hurdle, where they're allowed to continue their education long enough to be qualified to get a job.

And it seems the corporate world is now more willing to hire them.

"The entry point is now a good place to be," says Naina Lal Kidwai, former head of HSBC India and one of the country's most influential women leaders.

"I think there are firms that actively look at making sure their recruiting ratios are 50:50."

Naina Lal Kidwai

Many discriminatory recruitment practices have also been stopped.

"I remember 10 years back, most companies in India used to have tests for pregnancy," says Rajesh Dahiya, group executive at Axis Bank.

"Based on that, a woman would be hired or not hired. So these were things that have taken lots of time to change and I think lots of work has to be done still."

Discouraging behaviour

Some of that effort might need to go into improving attitudes towards women in the workplace.

"Women are not taken seriously at work. They have to prove themselves again and again," says Suruchi Sharma, a social media manager.

"A person actually came up to me and told me, 'You know what, it's okay if you don't get it, you don't have to be intelligent as long as you are pretty.'"

Ms Sharma thinks such behaviour dissuades women from having strong career goals.

Women are not taken seriously at work, says Suruchi Sharma

Ms Kasture, meanwhile, has worked for four large organisations over a 23-year career. Every time she started a new role or joined a new company she saw a similar pattern.

"I had to work a little harder, [be] a little smarter. I had to elbow my way into conversations to be relevant," she says.

"It's not discrimination, but there's an intense amount of hard work and you need grit to just stay the course. Then there's always a tipping point where suddenly the gates open, and you're a part of the club."

Motherhood and work

Jumping through hoops to stay at work, there's one in particular that Indian women are stumbling over.

A survey carried out by industry body Assocham found that a quarter of female professionals in the country quit their jobs after having their first child.

The government has been taking a proactive stance on this. A minister has called for all companies to provide childcare facilities for their employees. And India's lawmakers are all set to more than double maternity leave from 12 weeks to 26.

"I had to elbow my way into conversations to be relevant," says Vaishali Kasture

The announcement has had mixed reactions.

"[The] longer the maternity leave you give, the longer you're keeping women away from the network of the workplace," says Mr Dahiya.

"It's not going to help. I would advocate flexible hours rather than leave."

Ms Kidwai argues that it's not a big deal. "In my last organisation a woman could take a year off, maternity leave and other leave combined - it's one year in the full scheme of things.

"The ability to handhold them back into the organisation, so that they don't feel neglected or like they're doing the useless jobs - all of this needs to be practised."'

Challenging sexism

But Mr Dahiya does believe that on-site childcare centres could be a game changer. "There is a strong business case for it," he says.

"We have two large centres in Mumbai, each with 3,000 employees. We started a childcare centre in one of those - the attrition dropped to almost half."

Rajesh Dahiya says there is a strong business case for having childcare in workplaces

So far only a handful of companies offer these services.

And among all the changes that need to come in to get more women into work, Ms Kasture thinks the most important is a transformation at a basic level.

"There needs to be something which teaches our boys about equality of gender at a very young age. Until we change the dynamics at school, we will still be churning out the same mindset.

"India's made a lot of progress but sexism is not dead. Men have just learnt to hide it better."

- Published25 January 2016

- Published23 April 2015

- Published13 February 2015