Australia row hampers East Timor's oil ambitions

- Published

The government of East Timor is spending billions on new oil and gas facilities

Near Suai on East Timor's south coast, a rusty old oil pump sits near a beach, some mangroves and the ruins of an old prison from the Portuguese era. It's not good for much, but it hints at the country's oil and gas wealth potential.

East Timor is now spending US$2.1bn (£1.45bn) on roads, airport facilities and a supply base for offshore rigs along the south coast, with private investors expected to tip more in for refining facilities.

It is an attempt to grab a bigger slice of the country's oil and gas wealth, an ambitious project that the government hopes will transform the country's economy.

But its success might depend on solving an acrimonious dispute with its neighbour Australia over the maritime boundaries between the two countries. And as the dispute drags on, East Timor could be staring down the barrel of a crippling cash crunch.

Demonstrators went to the Australian Embassy in Dili, East Timor, in February

At present, there's a patchwork of agreements dividing up the oil and gas resources between the two countries. Even though there is now $16bn in East Timor's petroleum fund, the government contends that the current arrangements cheat it out of billions more.

East Timor wants a formal conciliation process under the UN convention on the law of the sea, but Australia doesn't recognise its jurisdiction. It wants to keep the existing treaties in effect, and says they are entirely consistent with the convention.

"It is regrettable that Timor Leste has taken a combative approach to this issue," the Foreign Minister, Julie Bishop, said in a statement.

Furthermore, Australian diplomats have suggested that East Timor's insistence on a permanent maritime boundary would actually leave it worse off, external.

Raw deals

Still, there's a pervasive feeling here that Australia's taking more than it is entitled to, and that it bullied a new and vulnerable country into a raw deal when the first treaty was signed shortly after its independence.

There's no doubt that the country was in a tough place. The World Bank estimates that 70% of the country's infrastructure was destroyed in the violence that followed the Timorese vote for independence from Indonesia in 1999.

"We needed money for development. And Australia used that opportunity to push us. We made a deal because we were weak at the time. But now we want to change the deal because we see that we are strong today. We realise that we have rights," says Juvinal Dias, who works at local think tank L'ao Hamutuk as a researcher on the oil and gas industry.

He also organised East Timor's recent protest against Australia, which was an indication of the strength of feeling here. By some counts, 10,000 people showed up for two days of protests, calling for a maritime boundary. That's a big crowd in a city of maybe 250,000. They said Australia had cheated East Timor out of $6.6bn in revenues.

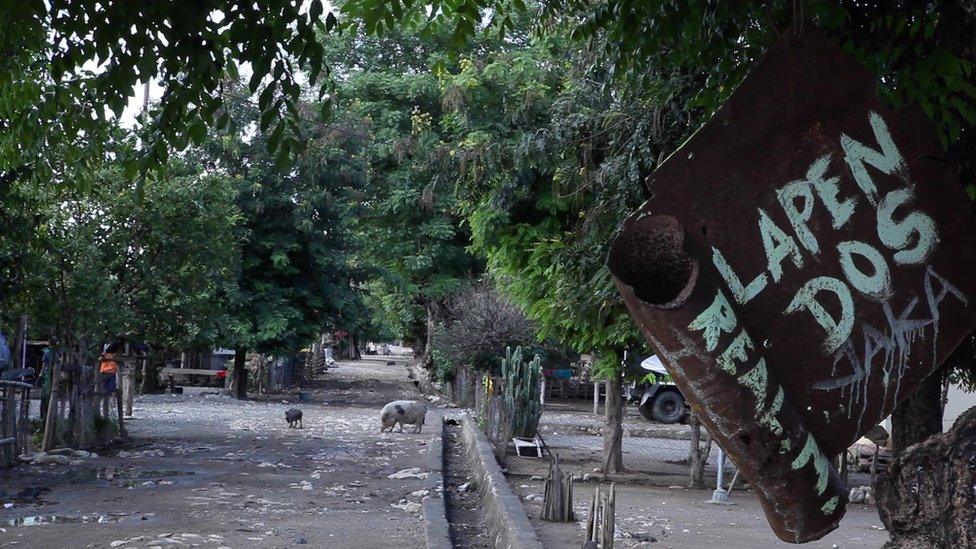

Despite its resources wealth, East Timor is still one of the poorest countries in Asia

Australia's position is practical and legalistic. And to most Australians, it's an abstract dispute over resources that are far away and under water. Nobody is standing outside East Timor's embassy in Canberra with signs pushing Australia's case.

In fact, there's some sympathy for the Timorese position. The Australian Labor Party says it will commit to renewed negotiations over a permanent maritime boundary and binding UN arbitration if they fail. Of course, that depends on it winning the election on 2 July. And a Liberal government looks highly unlikely to budge.

The Timorese see it very differently. Many here see it as a continuation of their independence struggle - the last bit of unfinished business that would give it the respect of true nationhood.

"It's a sovereignty issue for us, it's not oil resources," Prime Minister Rui Maria de Araujo says. "And we think that 13 years ago, we'd restored our political independence, interrupted by 24 years of Indonesian occupation, but so far we feel like the sovereignty of this country was not complete yet because the maritime boundaries were not established."

Undersea oil challenge

There is no permanent maritime boundary established between Australia and East Timor

Australia and East Timor have entered into three provisional revenue-sharing treaties regarding oil and gas in the Timor Sea

East Timor receives 90% of petroleum revenue from the Joint Petroleum Development Area that the countries share

But East Timor believes Australia is getting far more than it is entitled to under the United National Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

The small nation wants to establish a maritime boundary with Australia that is equidistant between the two nations

The Australian government says that the current arrangements are consistent with UNCLOS, and claims an equidistant maritime border will actually reduce East Timor's revenue

Swift resolution

Still, there is considerable pressure from the oil and gas sector to get the dispute resolved quickly.

The Greater Sunrise area could be worth tens of billions of dollars, and this dispute is standing in the way. The company that's leading the joint venture, Woodside, wants a swift resolution.

"It is vital that both the Timor-Leste and Australian governments agree the legal, regulatory and fiscal regime applicable to the resource. Once government alignment is established, we believe there is an opportunity to proceed with a development that benefits all parties," a company spokeswoman said.

More people turned out in March to show their anger outside the Australian Embassy in Dili

One of the other joint venture partners, ConocoPhillips, agrees that nothing will go ahead until there's "alignment".

The government-backed oil and gas company Timor Gap concedes a drawn-out negotiation will hurt, especially since the infrastructure it is building is aimed at processing oil and gas from Greater Sunrise.

"There'll be some influence or impact when things actually drag on in the maritime boundary negotiations. But it's not one that will put an end to Timor Gap's operations or future business," says chief executive Francisco Pereira.

What's more, the government's revenues are likely to fall sharply without a new source of income. The public purse is almost entirely dependent on oil and gas revenues, and the investment returns it derives from them.

East Timor set up a petroleum fund to manage the wealth generated from its resources. It provides a whopping 90% of the government's revenues. Currently, it has $16bn, which puts East Timor in the enviable position of being able to cover its entire national budget nine times over.

'Tapped out'

But it's fragile wealth. Spending is increasing while revenues are shrinking dramatically. East Timor's existing oil and gas projects are running dry, and the revenues will slow to a trickle in the coming years.

About $718m will top up the fund this year, but it won't even turn out a tenth, external of that by 2020.

East Timor's resources are highly valuable

ConocoPhillips says the only resources project still operating, Bayu-Undan, will be tapped out within six years.

The budget's getting bigger, and the revenue base is shrinking. And the World Bank says something's got to give.

"Such an increase in expenditure could eventually lead to the petroleum fund balance reaching zero and the government facing a cash-constrained budget," according to the World Bank's most recent assessment., external

"Standards of living would sharply fall and there would likely be a negative impact on political stability."

But the prime minister says this fight is about a principle, and East Timor is in it for the long haul. Since its independence, many of the country's leaders have been former guerrillas, who spent years in the jungle fighting Indonesia.

Although Mr Araujo is seen as a cool-headed technocrat, and something of a generational change, he perhaps retains some of the attrition-minded mentality of his predecessors.

"Don't forget, we fought the Indonesians for 24 years," he says.

- Published23 March 2016

- Published14 April 2023

- Published5 June 2023