A brighter future: Can tourism help rebuild East Timor?

- Published

East Timor hopes its unspoilt beaches, as well as its historical and cultural attractions, will draw tourists

On the road that goes from East Timor's capital of Dili to Suai, on the Island's south, there's a cross by the roadside. It commemorates Jakarta Dua, or Second Jakarta.

The Timorese say that during the Indonesian occupation, captive Timorese were brought here. They were told that they were being taken to Jakarta, but were instead tossed from a cliff into a ravine.

Timor fought a quarter century-long independence struggle against Indonesia, and there are some incredibly sobering reminders here of how brutal the conflict was.

But East Timor, also known as Timor-Leste, eventually won its independence. And now, it's hoping its darkest days will be part of a brighter future.

"The guerrilla tracks are places that have not yet been explored. So the focus now is to create the necessary environment for this type of tourism to grow," says Prime Minister Rui Maria de Araújo.

More than beaches

Already, tourists are visiting sites that focus on the independence struggle.

In Dili, there's a museum to the resistance. Some also visit Santa Cruz cemetery, where hundreds of students were gunned down by Indonesian troops in 1991.

In Balibo, there's a small memorial to five Australian journalists who were killed during the Indonesian invasion in 1975.

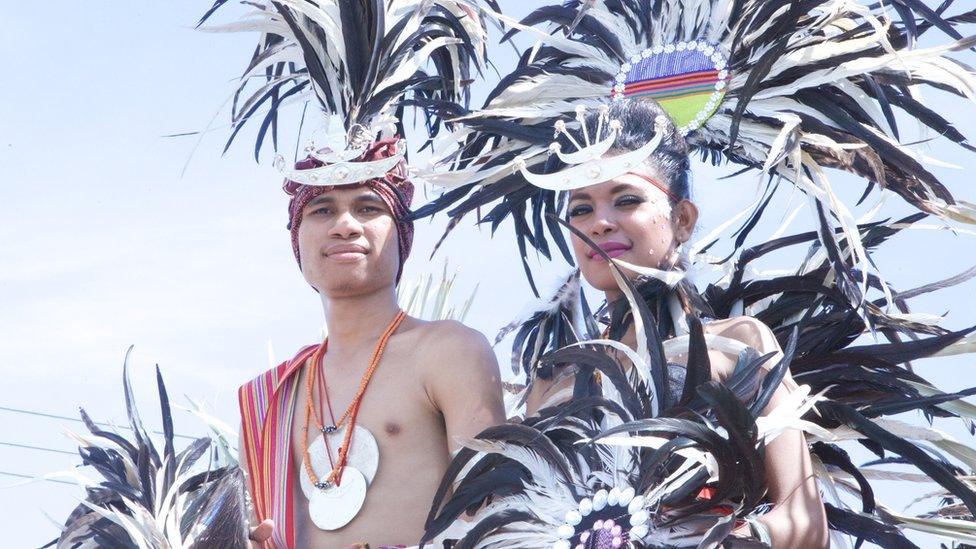

East Timorese traditional costumes and face paint worn by Caravana festival participants

East Timor wouldn't be the first country in South East Asia to earn tourist dollars from its difficult recent past. Cambodia and Vietnam both trade on theirs.

But East Timor took 24 years to gain its independence, and it's a victory that permeates the national identity.

"This young country is still finding its story and it's important that that story is one that is constantly changing and developing as the nation develops and grows," says Susan Marx, the Asia Foundation's country representative.

"So for the moment I think harnessing the very brave history of the independence struggle in Timor-Leste is important coupled with the magnificent countryside. So let's see where it goes," she says.

Colourful culture

The tourist boards of many South East Asian countries know that unique culture can be a big draw.

Every year, Timor has it's own carnival-style celebration. They're big, loud and colourful

East Timor is unusual in the region. It's a Catholic, former Portuguese colony. But the country's indigenous traditions are very strong too. It makes for a very colourful mix.

Every year, Timor has it's own carnival-style celebration. And a few months later, it has another parade and float celebration called Caravana.

Neither has the scale or the more risqué qualities of Brazil's carnival. But they're big, loud colourful celebrations.

Experts see potential here too.

Not Bali or Phuket

But the major challenge in monetising its history or its culture is getting the infrastructure up to scratch. Even the tourism locales that are thoroughly on the beaten track are poorly served.

Atauro's coastline offers visitors peaceful, empty beaches

The island of Atauro is about an hour-and-a-half by boat from the bustle of Dili.

There's a beach with beautiful mountain scenery behind it. Waters lap at a few outrigger boats along the shoreline. The sea is crystal clear and the nearest reef is an easy swim from the beach.

It's as pleasant as any beach on Bali or Phuket. And it's nearly empty. That's an attraction for some of the visitors, but the people who run businesses here aren't quite so happy about it.

They say a lack of utilities makes things harder.

"We only have electricity for 12 hours. Or sometimes only six. Sometimes none for months," says Lina Hinton from Barry's Place eco-resort.

Barry's has 28 employees and Lina says they need more customers. Right now, the majority are people who work in Dili for the UN or non-government organisations.

Partly, that's because East Timor is comparatively difficult and expensive to get to. There are just three flights a week from Singapore, three per day from Bali, and eight per week from Darwin.

Getting around can also be a pain.

For example, the 150km drive from Dili to the south coast takes about seven hours in a (completely necessary) four wheel drive.

Most tourists arriving in Timor want to taste the country's history or its culture, a survey says

And things often don't go smoothly. It's the sort of place where trips get cancelled shortly before they happen because a tourist operator can't find a car or where hotel staff can't work the credit card machine and direct you to an ATM next door that doesn't work either (both happened to me).

For some the extra effort is worth it for the sake of a more unique experience. But tourist dollars have a way of gravitating towards convenience.

Why Timor needs tourism

Currently, tourism is East Timor's third largest economic sector after resources and agriculture.

Whereas, gas and oil, and the interest generated from these sectors, provides 90% of government revenue.

East Timor's focus will be on community tourism rather than an industrialised approach

But revenues are expected to fall dramatically over the coming years, as existing oil and gas projects start to run dry.

And while the oil and gas sector dominates the economy, it doesn't generate much direct employment. Most of the action is offshore, and the government merely reaps the royalties.

Tourism, by contrast, has the potential to generate many jobs for East Timor.

"I think if you look at the possibility and potential for employing Timorese in an industry where there is an opportunity for them to gain skills that are far more attainable than becoming an oil and gas engineer, I think the follow on impacts of investing in the tourism industry is vast," says Ms Marx.

For the moment, though, the Prime Minister says East Timor is not looking to be the next Bali.

"The focus will be on community tourism. We don't want to get an industrialised approach to tourism in the country," he says.

It may not seem hugely ambitious, but it might be a more realistic target.

Bali and Phuket now have multi-billion dollar tourism industries, but they had to start somewhere too.

- Published13 June 2016