When will US interest rates rise again?

- Published

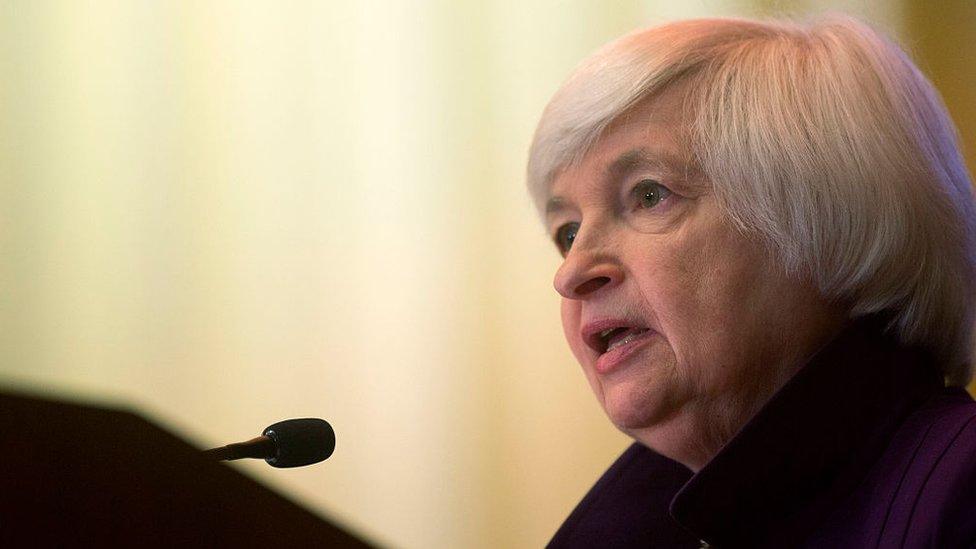

Fed chair Janet Yellen has made it clear the US central bank is always ready to change its plans if new figures improve the economic picture

Perhaps the playwright Samuel Beckett was a secret economist.

We are about to enjoy (!) the next act in the absurdist drama "Waiting for the Fed" (to raise interest rates again).

Truth be told, we can be fairly sure how this scene will play out. Once again no increase in rates. Perhaps Godot will turn up first.

The Fed is holding a policy making meeting and an interest rate rise is in theory at least on the agenda.

Janet Yellen, the Fed Chair, and her colleagues would like to get rates back to more normal levels. The Fed currently aims to keep its main policy rate (the rates banks offer to lend to each other overnight) within a range of 0.25% to 0.5%.

They raised it to that level in December last year, from practically zero where it had been since the depth of the financial crisis.

But nobody expects they will hike rates at this meeting, largely because of the very weak performance of the jobs market in May.

"Disappointing and concerning", is how Janet Yellen described May's job data

The number in employment rose by only 38,000, the fewest since September 2010. Because the US population is growing, the number of people with jobs has to rise by more than that just to keep pace. Employment growth in April was better, but still not all that strong.

It's true that the unemployment rate fell markedly in May, to 4.7% from 5%. But this was due to a decline in the number of people looking for work. They are counted as "not in the labour force" rather than unemployed, even if they would like to have a job.

In a recent speech, external, Ms Yellen described the May jobs report as disappointing and concerning. She did, however, manage to find one encouraging thing; a faster increase in average hourly earnings. After a long period in which the economic recovery has failed to have much of a favourable impact on pay it was, she said, "a welcome indication that wage growth may finally be picking up".

Inflation is another factor that encourages the Fed to feel it has no need to rush the next rate rise. The latest figure for the inflation measure the Fed prefers was 1.1% in April, compared with its 2% target.

One bad month?

That it is so low reflects some transitory factors, including the strength of the dollar (which makes imported goods cheaper) and the decline in energy prices over the last two years. But in time, those factors cease to have a direct impact, so Ms Yellen expects inflation to move back towards 2%.

She also said that it's important not to attach too much significance to a single monthly jobs report. In short, a good report next month could bring interest rate rises a lot closer.

The production of goods and services is now well above its pre-recession peak

So while investors think the date of the next rate increase has gone further into the future as a result of the May jobs data, the Fed is always ready to change its plans if new figures change the picture.

Long term picture

Looking at the US economy from a longer term perspective, it is a remarkable state of affairs that we should have rates still so close to record lows in a recovery that has been underway for several years.

The US economy started to grow again in the second half of 2009. Since then it has expanded in 25 out of 27 quarters. The production of goods and services, GDP, is 10% higher than the pre-recession peak, and it's 15% up from the low it reached during the downturn.

There has, however, been a slowdown in the growth of productivity in the US, external, which pre-dates the recession.

The labour market has also gained strength despite May's disappointment. The unemployment rate is now 4.7%, compared to 10% in October 2009. The number of people with jobs has increased by 14 million from its low point in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

But the US has not managed to get back to pre-crisis levels for the percentage of the working age population with jobs. The latest figure is just below 59%. In 2006 it was more than 63%.

The number of people who want to work but aren't has declined markedly over the last few years

Some of the decline is due to long term factors. The US population is ageing; many of the baby boomer generation are retiring. More young people are taking post-secondary education.

The recession and its lingering after effects also had an impact. The Bureau of Labor Statistics in the US publishes figures on the number of people who want to work but haven't looked in the last four weeks, and for people working part-time who would like longer hours.

A long way

This group, plus those who are officially classified as unemployed, add up to what is sometimes called "slack in the labour market"; people who want to work but aren't.

The numbers have declined markedly over the last few years, although one of the concerning things about the May report was a reversal on one aspect; there were more people wanting longer hours.

Nonetheless Ms Yellen said in her recent speech: "I believe we are now close to eliminating the slack that has weighed on the labour market since the recession".

The US economy has come a long way from the panic of late 2008. The Fed's interest rate policy has started the journey back to normality. But it will be very slow. And the US can't be considered immune to turbulence that might hit the global economy.

- Published3 June 2016

- Published27 May 2016