How cinema is striking back against home entertainment

- Published

Suicide Squad will be coded for "immersive" 4D technology as well as 3D and Imax 3D

The advent of giant smart TVs and video-on-demand services like Netflix has turned our homes into comfortable mini cinemas.

So you'd think public cinemas would be struggling to compete. Not a bit of it.

Millions still flock to the big screen, with movie theatres adopting the latest technologies to keep us coming back.

Last year was a bumper 12 months for the movie business, with global box office takings hitting a record $38bn (£29bn; €34bn), including an unprecedented $11bn in the US.

Revenue at UK cinemas jumped by 17.3%, with the number of tickets sold up 9% to almost 172 million - helped considerably by Star Wars: the Force Awakens, which became the highest-grossing film of all time in Britain.

Cinema operators are hoping that the new wave of "immersive" technologies - seats that move, laser projections, sensory experiences - will make vegging out on the sofa watching endless box sets seem less attractive.

4DX uses motion, blasts of air, water and scents to create an "immersive" experience

This new 4D cinema, as it's called, is offered by the likes of D-Box, external and 4DX, external.

D-Box's seats only move a maximum of 1.5 inches, but Michel Paquette, the Canadian company's marketing chief, says: "We can trick the brain to make you believe you're in the movie … it's so well timed with the soundtrack and the visual that we bring another level of narrative to the storytelling."

This technology can add "magic" and a "wow factor" to movies, he believes.

One of the films coded for D-Box was 2015's The Walk, in which Joseph Gordon-Levitt played Philippe Petit, the Frenchman who walked on a wire between the twin towers of New York's World Trade Center in 1974.

The Cineworld multiplex in Ipswich, England, boasts both an Imax screen and 4DX seating.

Mr Paquette says the technology allowed the audience to "feel" the pressure of the steel cable.

South-Korean-based 4DX goes even further, offering something of a theme park ride, complete with blasts of air, water, scents, and even fog and bubbles filling the auditorium.

Although there are only about 1,000 screens globally (less than 1% of the total) using this kind of 4D tech, that number is rising fast, industry observers say.

D-Box, the market leader, expects to be in 1,000 theatres by the end of this year. And the UK's first 4DX screen opened at Cineworld in Milton Keynes early last year.

Exhibitors typically install a row of "immersive" D-Box seats in a cinema

Installing a couple of rows of D-Box seats in a cinema costs about £75,000, which also includes the technology in the projector booth. That allows them to charge a premium of about £6 a ticket in addition to the extra cost of 3D and/or bigger screens such as the Imax format.

4DX has been most popular in China, where one of its partners is the Wanda Group, which this week announced a deal to buy Odeon - Europe's biggest cinema operator - for £921m.

The Chinese company, which also owns US chain AMC, was already the world's biggest movie theatre chain before adding Odeon's 242 sites and 2,236 screens.

Celluloid to digital

Phil Clapp, chief executive of the UK Cinema Association, says that while bells and whistles such as 4D and Imax have moved cinemas on, it's the switch from celluloid to digital that has had the most fundamental impact since the advent of sound.

That's because it cuts costs, lets cinemas easily switch titles between screens to respond to audience demand, and allows them to show a wider range of content, such as live theatre, opera, ballet - and even e-sports.

The new Ghostbusters movie remake was shot in 3D for big-screen audiences

"Digital makes cinemas more than just a place where people can go to see films," Mr Clapp says.

Neither are cinemas necessarily competing with home entertainment, as avid home film watchers also tend to be the biggest cinemagoers, he says.

"It's not a zero-sum game."

Giant screens and lasers

Hollywood studios are increasingly producing action-packed blockbusters, such as the new Ghostbusters, that demand to be seen on the biggest screen possible and appeal to filmgoers in every market.

Seven of the UK's biggest movies last year were available in 3D, including Avengers: Age of Ultron; Jurassic World; and Fast & Furious 7.

Will new technology help the silver screen retain its traditional glamour and lustre?

Analysis firm IHS estimates that global 3D box office revenues rose more than 10% to a record $7.8bn, driven by spectacular growth in China.

Some moviegoers have complained about the dimness of 3D films, but the advent of laser projection rather than those with traditional xenon bulbs is set to solve that problem - particularly as the size of screens continues to increase.

Charlotte Jones, principal cinema analyst at IHS, says exhibitors are starting to install laser projectors for their largest screens - up to 27m (88ft) wide - because they offer exceptional brightness (up to 60,000 lumens) for ultra-high definition (4K) films, as well as better colour contrast and lower power consumption.

Imax boasts a screen in Australia that is nearly 36m wide.

Barco's laser projectors are very bright, making them more suitable for really large screens

Kinepolis will soon open Europe's first all-laser site with a new 10-screen multiplex at Breda in the Netherlands, while Barco laser projectors will be installed in all 22 screens at the Reel Cinemas multiplex in Dubai.

"Laser will be the dominant technology for new cinemas," Ms Jones says.

Sound sense

And sound is also an important part of the immersive package.

Megascreens are usually paired with sound systems such as Dolby Atmos that deploy an array of speakers on the ceiling as well as the walls of a screen.

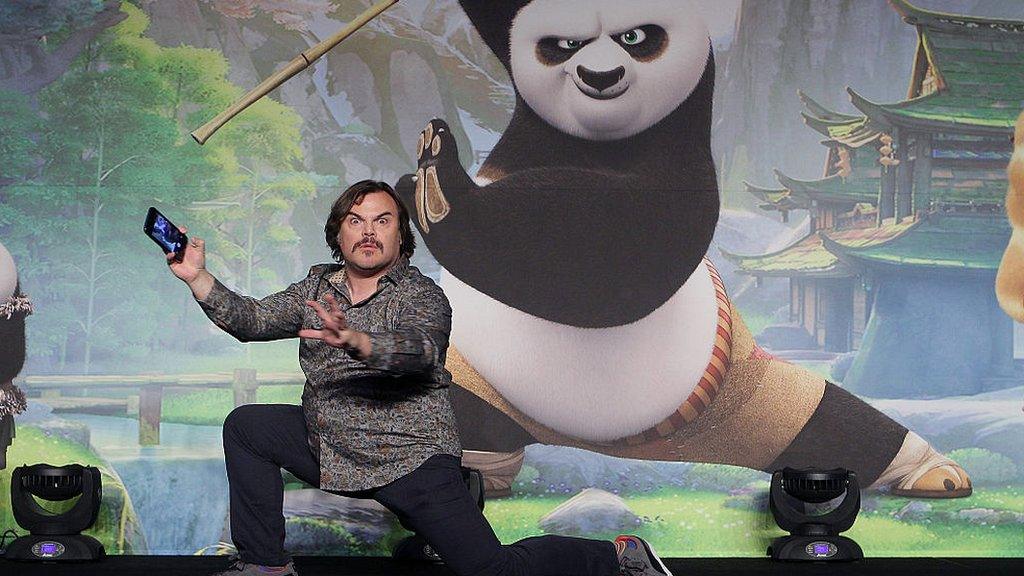

Summer blockbusters tailored for the system - which director Danny Boyle has described as "the next great leap forward" - include Ghostbusters; Star Trek: Beyond; and Suicide Squad.

Atmos links with the Dolby Vision system to form the Dolby Cinema package that aims to give moviegoers what it describes as a "completely captivating cinematic event".

All this technology helps moviegoers feel they are attending an event, not just watching a film, and should ensure the silver screen retains its lustre for some time to come.

Follow Technology of Business editor @matthew_wall on Twitter, external

- Published12 July 2016

- Published28 March 2016

- Published1 February 2016