Executive pay: A long running saga

- Published

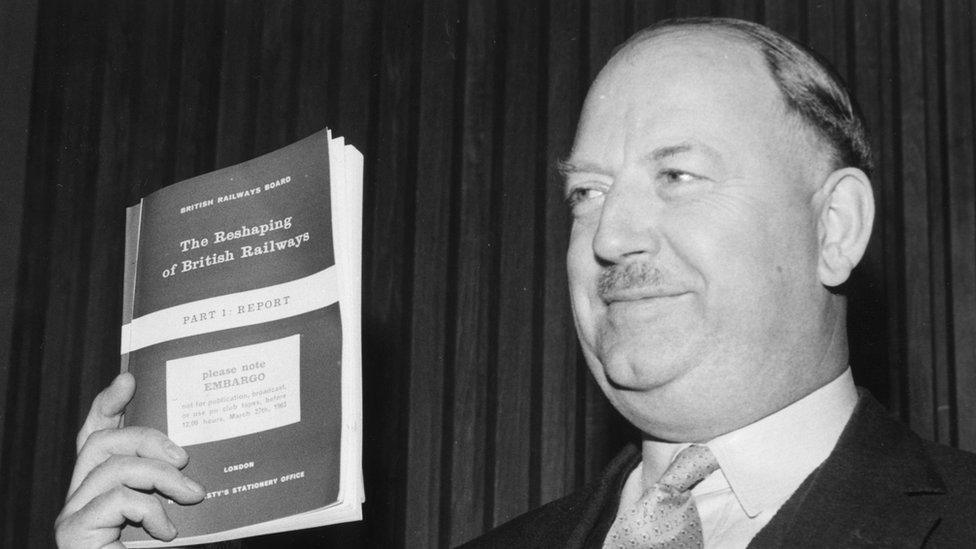

Dr Richard Beeching brandishes a copy of his 1963 report The Reshaping of British Railways

The average pay for chief executives of firms in the FTSE 100 index is now 144 times that of the UK's average salary, says the High Pay Centre, external.

But such apparently excessive pay is not a new concern.

Back in the early 1960s the Conservative government was interested in cutting back the sprawling and loss-making British railway network.

The man who was chosen for the job was a senior ICI director called Dr Richard Beeching.

He was appointed as chairman of the new British Railways Board in 1961 and two years later published his first, and infamous, report on "The Reshaping of British Railways".

Even before he devised his controversial plans for pruning British Rail, there was another controversy, at least in the newspapers - over his pay., external

The Times reported in 1961 that Dr Beeching would be paid the same as his ICI salary while he was on secondment to the government.

That was the then huge figure of £24,000, which was thirty times higher than the average annual UK salary of just over £800 a year and £14,000 more than that of the then Prime Minister Harold Macmillan.

"Is this man - or any man - worth pounds 450 a week?" thundered the Daily Sketch.

'Greed is good'

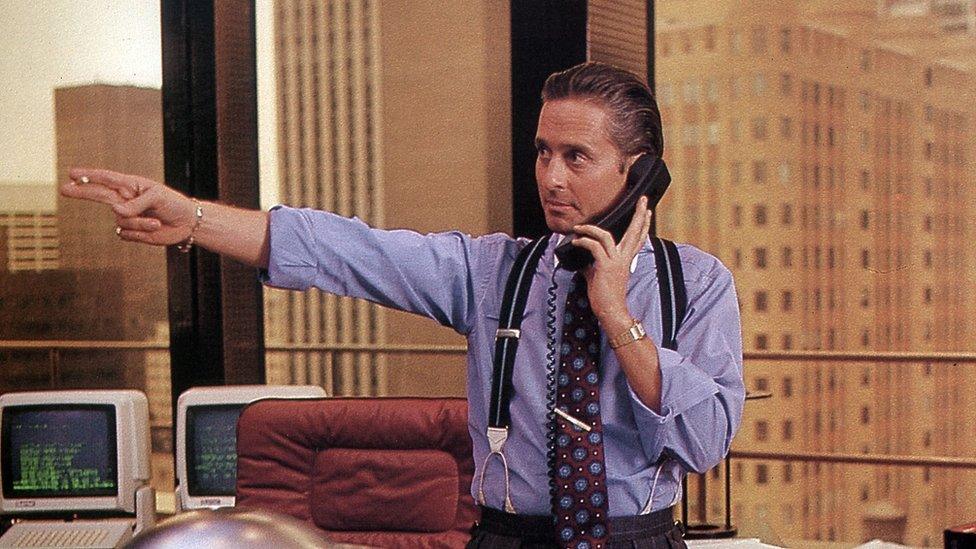

Michael Douglas as Gordon Gekko

Let's fast forward a couple more decades to the 1980s.

It was then that the current trend for spiralling executive pay took root.

According to some analyses, the touch paper was lit by the boom in City salaries that followed the Big Bang of financial deregulation in 1986.

That prompted not only a bidding war for City traders and the like, but attracted a rush of US investment banks who set up in London.

They brought with them American-style pumped-up salaries, so fitting for the "greed is good" ethos famously espoused by the character Gordon Gekko in the film Wall Street.

Outside the City, in 1987, the boss of the Burtons men's clothing firm, Sir Ralph Halpern, was paid £1.3m, becoming the first million-pound-a-year-businessman in the process.

Since then, we have seen a parade of ever-higher pay packages for supposedly top executives.

Fat Cats and Pigs

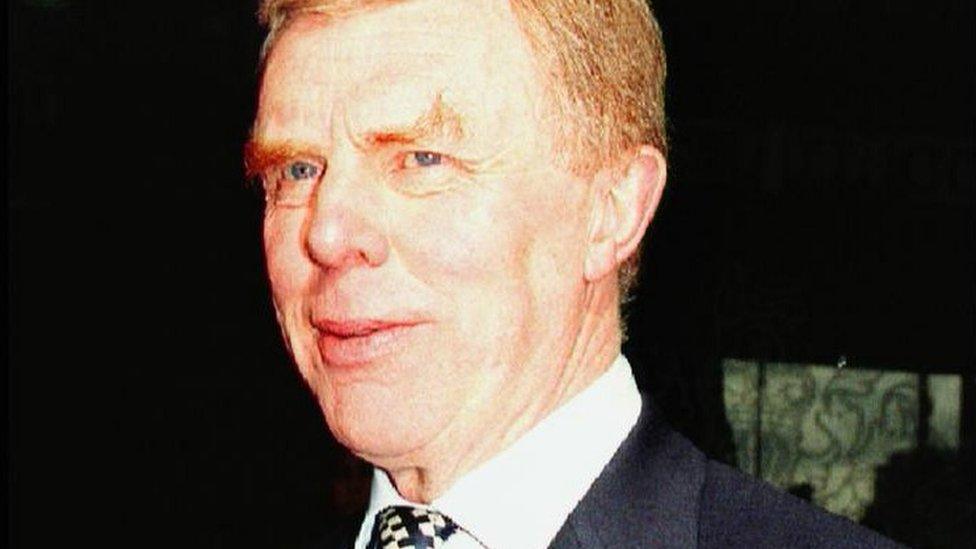

Cedric Brown, chief executive of British Gas

Public indignation over the issue boiled up.

In 1994, the then chief executive of privatised British Gas, Cedric Brown, was pilloried as Cedric the Pig.

He had enjoyed a 75% pay rise to £475,000 a year, for running what had been a boring state owned utility only a few years before.

By the late 1990s, according to the High Pay Commission, the ratio of top pay to average pay had risen to 47 times.

What could be done?

There were various reports into corporate governance in the 1990s (Cadbury, Greenbury and Hampel) which pondered, among other things, how executive pay should be decided.

None have had any effect on pay.

And from time to time even big City shareholders have baulked at some of the more generous pay deals that executives have been able to wangle out of their companies, arguing that shareholders have been taken for a ride.

'Who loses out?'

So how to explain the boom in top salaries and pensions?

The economist Paul Ormerod, who famously wrote a book "The Death of Economics" more than 20 years ago, wrote last year that we shouldn't look to his profession for an explanation.

"Economics has no theory with which to explain the distribution of income," he said.

"The simple fact is that executive pay is almost entirely determined by social values and norms. The sense of restraint, of noblesse oblige, which characterised much of Britain's post-war history, has vanished."

A study by the London School of Economics shows that bosses' pay in 2014 was 160% larger in real terms than in 1999, whereas an average worker's salary has risen by just 10% over that time.

But not everyone thinks "excessive" executive pay really matters.

That reliable supplier of contrary economic views, the Adam Smith Institute, said in a blog, external: "Ultimately, it's hard to see the public interest argument here."

"If shareholders are really missing a trick and overpaying their chief executives, who loses out?

"Well, shareholders, in the form of lower profits. And they're the ones who stand to gain if they can fix that problem."

- Published8 August 2016

- Published21 April 2016

- Published5 January 2016