Locals divided over Druridge Bay coal mine

- Published

Druridge Bay is seven miles of wide, sandy coastline in Northumberland, north east England. It doesn't have special protected status and it's not an official Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, but for people who live here and the many visiting tourists, it's the jewel in the area's crown. Or perhaps more like a hidden gem.

Lynne Tate lives in the area and spends time at the beach almost every day, come rain or shine. From the top of the sand dunes it is clear to see what makes this place so precious.

"It's special because it's quiet," Lynne says. "It's tranquil and the wildlife is vast."

So, like many others from the Save Druridge Campaign, external, Lynne was horrified to learn that permission had been granted by Northumberland County Council for a new opencast coal mine, called Highthorn, to open just 400m away from the dunes.

"The first thing you are going to notice is the 300 HGVs that are going to be coming in and out of Highthorn opencast mine every single day," she says.

Lynne Tate is worried the planned mine site will destroy the tranquillity of Druridge Bay

Plus there's the blasting that will happen up to four times a day.

"It's going to affect wildlife greatly, will cause dust, pollution, lights in the sky at night - generally spoil the tranquillity. It spoils everything that this place is well-known for," says Lynne.

Bad for business

Just on the other side of the sand dunes, is the bustling Drift Cafe at Cresswell. Owner Duncan Lawrence is worried the mine will deter tourists and seriously affect his business.

"We have plans to build a bunk-house for cyclists and walkers, to extend the cafe and to build a car park. These plans will be put in jeopardy," he says.

Cafe owner Duncan Lawrence fears the mine will put off tourists

Down the road the effects of the prospective mine are already being felt.

Neil Fairclough is company secretary of Eltham Caravan parks, which has been run from the location as a family business for 26 years.

Looking out from his site office, the boundary of the proposed mine lies just two fields away.

"People don't come to a caravan to listen to all that noise," he says. Even before the plans for the mine were approved by Northumberland Council, Neil says business was already down by "a six-figure sum".

The plans have been referred to the government for review but no decision is expected until Parliament reconvenes in September.

Friends of the Earth opposes the Druridge Bay opencast mine plan

It's not only locals who are against the plan.

Guy Shrubsole, a Friends of the Earth campaigner, says: "While we wait for the final decision from government we can only reflect on what a special place Druridge Bay is. It's clear to anyone who cares to look that an opencast coal mine would completely ruin the bay, cause massive disruption and only drive tourists away, and why? So a dying source of energy can wreck our climate."

History repeating itself

Of course the irony with all of this is that much of the landscape in this part of Northumberland was shaped by opencast mining that is still taking place inland.

Coal mining runs deep in the history of this part of Britain. It has torn up the countryside before, but in the decades that have followed, the land has recovered.

The Highthorn mine at Druridge is a seven-year project and after that time it will be rehabilitated. This means there's nothing to worry about in the long run, according to Banks Group, the local company behind the mine.

Jeannie Kielty is its development relations co-ordinator. She cites the nature reserve at Oakenshore, near Durham, as an example of how successful this rehabilitation can be. Created from one of the old surface mines that Banks used to operate, it's an impressive place with lakes and green meadows carpeted with flowers, all surrounded by a forest of trees.

She does admit that it's taken 15 years to get to this stage, but is adamant that tourism and mining can co-exist.

Jeannie Kielty of Banks Group says the mine site will be rehabilitated once the project is complete

The tourist attraction Northumberlandia, external is one example. Using the waste heaps from the Shotton mine next door that's still going strong, the company has created a series of landscaped hills in the shape of a woman. From the top you can look down into the mine itself.

The Highthorn site will mostly be converted back into farmland, with some land becoming a nature reserve. Money will also go towards developing local tourism. But even if the mine at Druridge Bay can be rehabilitated, is a new coal mine even needed?

Last year was terrible for the UK industry. Overall coal production was the lowest on record, with imports hitting a 15-year low. Demand for coal by electricity generators was also down by a quarter.

The Northumberlandia site is a system of pathways and mounds shaped like a woman

In May this year there were two days where the UK electricity generated from coal hit zero for the first time ever. Plus the government has promised to phase out coal-generated power entirely by 2025.

Banks Group has mothballed its Rusha mine in Scotland early, external, because it couldn't get a good enough price for the coal.

Nevertheless, the company promises its new development will provide 50 new jobs for the area.

Much needed jobs

Three miles down the road from Druridge Bay is the village of Widdrington Station. The majority view here is that the mine should go ahead.

One man who did not want to be named says the area desperately needs the jobs.

Another woman who works at the supermarket has a partner working at a different mine that is coming to the end of its life and is facing redundancy.

"I think it should go ahead, opencast mining has been here for a lot of years and it has never hurt anyone. It's a really beneficial thing for us… it needs to go ahead."

But is the short-term preservation of jobs really enough to make the new mine worth it?

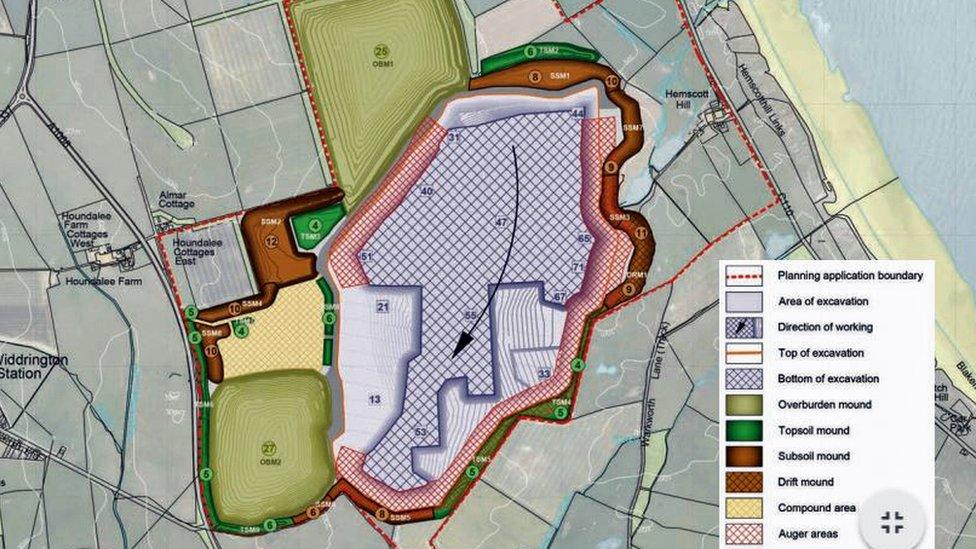

The Druridge Bay mine would be worked in sequence with significant areas left undisturbed at any one time, says Banks Group

Jimmy Aldridge, a senior research fellow at the Institute for Public Policy Research, says that while it is important to respect the history of coal mining in the area, the government needs to think about what happens when there is no demand for coal beyond 2025.

"Any new opencast coal mine is only a short-term development, we need to think about what happens to employment longer term," he argues.

"In seven years those jobs will disappear and we need to think what happens to those jobs when it gets to the end of the life of that particular project, how to retrain and re-skill [the workers]."

Banks Group argues there will always be a place for coal in the UK, and importantly the mine will help reduce reliance on imported coal from Russia and Colombia.

Nevertheless, Anne-Marie Trevelyan, MP for Berwick-upon-Tweed, has written to the Communities Secretary, Greg Clark, asking him to intervene and remove the application from the control of Northumberland County Council.

It's a drastic step, and still may not stop Druridge Bay from becoming the site of Britain's newest coal mine.

- Published5 July 2016

- Published27 February 2016

- Published19 August 2015