The UK's last deep pit coal mines

- Published

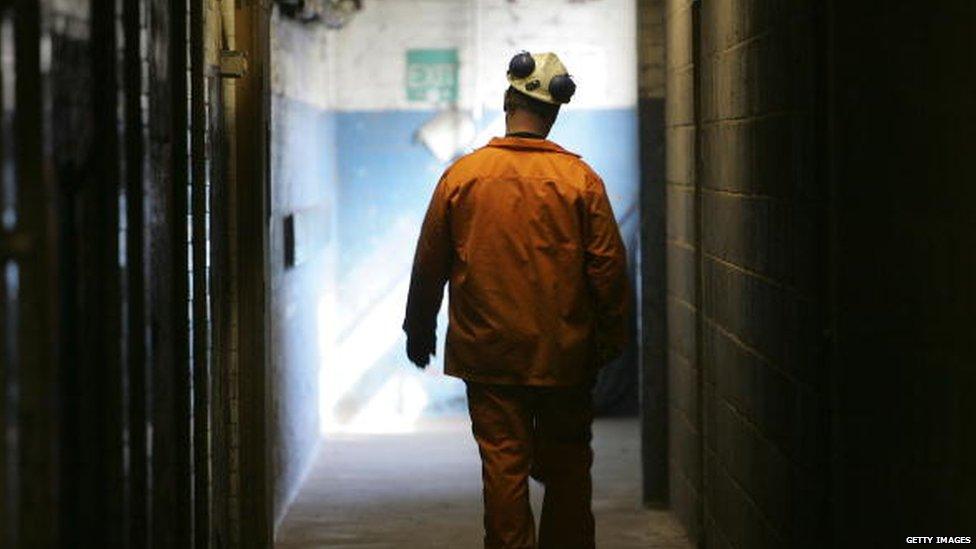

The UK's very last deep pit coal mine is about to close. The BBC's former labour and industrial correspondent, Nicholas Jones, reflects on the end of an era.

Coal heated our homes, fuelled the industrial revolution, and over the centuries provided millions of jobs in coalfields across the UK, but soon deep mining will be no more, and a way of life is about to end.

"It's absolutely heart-breaking," says Dave Douglass, a former pit delegate and secretary who has spent his life working at the recently-closed Hatfield pit near Doncaster.

"The only way that a non-professional working class lad could earn a decent living, buy a house and get a decent car and holiday was by being a miner, and being a miner was a very proud thing to be."

Before it shut down in July, Hatfield was one of only three remaining privatised deep pit mines in the UK.

Thoresby in Nottinghamshire also ceased production in July. Both are now being dismantled, leaving just Kellingley pit near Castleford - and that's closing in early December.

The Yorkshire super pit once employed 3,000 people, and was the biggest deep mine in Europe.

Once a pit closes all the equipment is removed and the shafts are sealed. Spoil, or waste heaps, are sometimes planted with trees - many becoming nature reserves and woodland open to the public. In some cases, the former colliery land has been transformed into new industrial estates.

Kellingley, like the two other pits, still has vast reserves of coal in the ground - but could not compete in the face of cheaper imports, the lack of investment, increases in carbon tax on generating electricity from coal, and the switch to green energy.

Great fortunes were made by the mine owners and the coal fields provided regular employment for successive generations. But they were also a scene of devastating industrial conflict.

The National Union of Mineworkers became the shock troops of the British trade union movement - their 1974 strike brought down the Conservative government of Edward Heath, and it was the year-long strike of 1984-85 that sealed the industry's fate.

Without an agreement from the union on long-term contracts and guaranteed prices, the National Coal Board faced an uncertain future after the strike. By the early 1990s, there were still 50 pits, but more closures followed when the privatised electricity-generating stations switched to imported coal. A third of the UK's electricity is still generated by coal-fired power stations but the coal is imported.

It's a desolate scene now at the Hatfield Colliery - but the plan is to landscape the area

I have always believed that if only there had been an agreement in the 1980s to ensure the long-term delivery of coal to the power stations, a slimmed down industry might well have survived, and the UK would have had a chance of continuing to lead the world in deep mining, and latterly in the clean burning of coal.

Many politicians and business leaders take a different view. Deep mining has always needed constant investment in new pit faces and equipment. Privatisation has shown that without government or EU funding the industry cannot compete with the cheaper imported coal available on the world market. Successive Conservative and Labour governments have not been prepared to offer the kind of subsidies that are needed and the privatised industry became so small that it was no longer viable and would no longer be profitable.

But the point remains, in the 1980s the UK led the world in deep mining - and was developing clean burning coal technology. The country had a chance to slim down the industry, bring in the most modern equipment and lowest possible manning levels and still be able to compete. That opportunity was lost.

"The one thing I could and should have done, and regret not doing to my dying day is to make incessantly and repeatedly the call I made several times privately, and made several times publicly, for a ballot," Neil Kinnock, who was elected Labour Party leader the year before the 1984 strike began, told Newsnight.

"That would have categorically changed the circumstances and produced a process of negotiation. Had we not had that devastating strike and its after-effects, there would still be a viable coal industry."

The miners' strike 1984-85

Thoresby mine during the 1984 miners' strike - it closed in July this year

Year-long industrial action by National Union of Mineworkers, led by Arthur Scargill, in protest at Conservative plans to close 20 pits, with the lay-off of 20,000 workers

The biggest strike in the post-war era (at its height, 142,000 mineworkers were involved), it was also one of the bitterest industrial disputes in British history

The strike ended on 3 March 1985 with the NUM having failed to achieve concessions from the government

Kinnock met Arthur Scargill, the president of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), within weeks of taking office. He said they agreed to campaign together for a new plan for coal, but that understanding was shattered the following March when Scargill and the NUM leadership backed a strike without a pit head ballot.

By the early 1990s, British Coal's output and efficiency were at record levels, but the power firms were moving towards cheaper imported coal.

In 1992 Michael Heseltine, then President of the Board of Trade, announced a round of 31 pit closures and compulsory redundancies. Arthur Scargill and the other miners' union leaders were back on the streets, this time not picketing - but marching through London evoking widespread public sympathy.

1992: Arthur Scargill leads march in protest at mine closures

Heseltine still believes there was no alternative but to go ahead with the closures.

"I did everything within my legal and reasonable powers to persuade them, but they simply said we can buy coal cheaper on the markets and no deal was done, so there was no market for anything other than a fraction of British deep-mined coal. That led me to the uncomfortable, controversial decision that I had to close 31 pits."

When the remaining pits were privatised they were effectively consigned to a slow death, having to make do with short-term contracts that meant they lacked investment and did not have the capacity to develop.

When Kellingley closes in December, there will be no more deep pit mines anywhere in the UK

Without further government support and the opening of gas-fired power stations, coal lost its potential lead in clean burning, and new mining, technology.

UK Coal, which owned Kellingley and Thoresby, said the two pits had been in financial difficulty for some months.

A failure to get further government support forced the Hatfield pit, near Doncaster, into receivership. Production stopped in July and the few men kept on to dismantle the pit face an uncertain future in a region that once boasted the highest manual earnings in the country.

"It's been my livelihood. It's all I know, and that goes for a lot of the men," says Derwin Martin, another miner who spent his working life at Hatfield, where he started as an apprentice in 1978.

"It was the camaraderie. Everyone wanted to work at a coal mine. You came to work and enjoyed it. I enjoyed it all my life and I would have loved to continue until my retirement age. Everyone joined the industry thinking they would get to a retirement age.

So coal was king?

"Yes, coal was king. I am distraught, to be honest. I don't know what I will do for the rest of my life. It is the end of the road unfortunately, the death knell has sounded."

Nicholas Jones was named 1986 Industrial Journalist of the Year by the Industrial Society for his BBC coverage of the 1984-85 miners' strike and its aftermath. Watch his full report for Newsnight here.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.