Long wait for families to identify missing migrants

- Published

Children trying to reach Italy rescued from the Mediterranean

Human rights researchers are warning of a "devastating" lack of information for families of migrants thought to have drowned in the Mediterranean.

More than 6,600 refugees drowned in the Mediterranean in 2015 and the first half of this year.

But a report by UK academics warns that most bodies remain unidentified, external and their families are left not knowing if missing relatives are dead or alive.

This is an "invisible catastrophe", said report author Dr Simon Robins.

"This is devastating for their families back home," said Dr Robins, senior research fellow at the Centre for Applied Human Rights at the University of York.

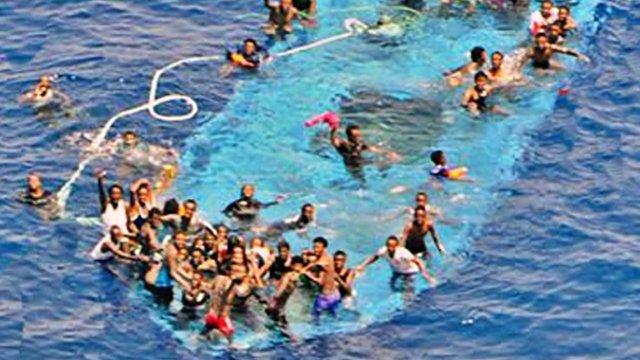

Refugee families rescued off the coast of Libya this week

"They likened it to a form of torture where they are caught between hope and despair, not knowing whether they would ever see their loved one again, not knowing if they should give up hope and focus on the rest of their lives.

"More than anything these people want to know if their loved one is alive or dead. If they are dead, they want to bring their relative home and have them buried visibly in their community."

More stories from the BBC's Global education series, external looking at education from an international perspective and how to get in touch

Researchers from the Mediterranean Missing Project, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, spent a year in Italy and Greece examining how information about dead migrants was gathered.

Dr Robins says that only a minority of the bodies are identified - and many more migrants will have been lost and never found at sea.

When bodies are identified it is usually by relatives coming to where bodies are kept before burial, he says.

A sinking ship in a picture from an EU rescue operation - up to 30 people had drowned

This means families without any way of travelling to Europe might never get the chance to see if their loved ones are among the bodies which have washed up.

The report, from the University of York, City University London and the International Organisation for Migration, calls for a more systematic approach to gathering data about those who have drowned.

Interviews with families from Syria, Iraq and Tunisia with missing relatives:

"I don't feel anything, anymore. My feelings are dead. I was waiting for a phone call, I was sure he was still alive. Do you want me to tell you the truth? Actually, I don't know anything about him. I don't know if he passed away or is still alive."

"We often fight. He is convinced that our son is dead. My other children are convinced that he is alive... I even asked them not to change their phone number; you never know if my son would try to contact one of us."

"I try somehow to explain to them that he is in Italy and he will come back. They know, however, that their father is gone, but I try to make them wait. I found no words to say to them... I myself have not heard from him."

"I tell them that as long as I'm breathing, I'll keep looking for my son until my last breath. I'll never give up!"

"Another man got in touch with me saying he knows where my husband is, but it turned out he was a liar and was after money and tried to threaten me."

"Some people said they saw her in Izmir in Turkey, while others said she was seen in Limbach in Germany... there was a family from Damascus with them on the boat, perhaps she left with them... Others posted on Facebook that she was seen in Izmir, we contacted them, but they deleted their post later."

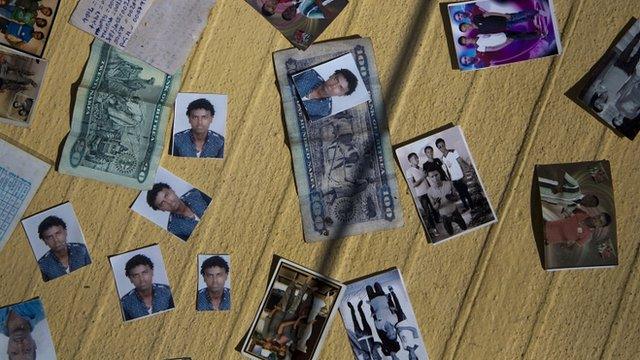

Belongings of migrants gathered in a rescue off Libya this weekend

Dr Robins said researchers saw personal objects - such as credit cards, watches and even a passport - that had washed ashore on beaches but had not been gathered to help identify those who might have been lost in the Mediterranean.

Local authorities have been "overwhelmed" by the tide of migration, says the report, and this has put pressure on attempts to identify the dead and inform their relatives.

"There is a policy vacuum around the problem, marked by minimal co-operation among different state agencies, a lack of effective investigation, and little effort to contact the families of the missing," says the report.

The grave of an unidentified migrant drowned at sea and buried in Turkey

In Italy, there has been a special commissioner for missing persons created, which, Dr Robins says, has been very effective in investigating shipwrecks.

But Dr Robins says this work does not extend far enough and that in Greece there is even greater need for a more co-ordinated approach.

There have been efforts to gather DNA material from those who have drowned, but Dr Robins says this needs to be more systematic, so that families would be able to seek a match for a lost relative.

The wave of migrants trying to cross the Mediterranean is still continuing, with 6,500 rescued on Monday between Libya and Italy.

Turkish police remove the body of a migrant from a beach

The report also calls for a more thorough approach to interviewing survivors rescued from the Mediterranean, who might know the identities of those who have drowned.

The lack of centralised information means there is no straightforward point of contact for families looking for lost relatives.

Dr Robins says there needs to be a much greater effort to find these families, who have been "marginalised" by the lack of information.

These families are the hidden victims of the migration crisis, says the report.

A love letter found with a Syrian woman whose body was found on the coast of Libya

Researchers interviewed 84 families from Syria, Iraq and Tunisia whose relatives disappeared trying to cross the Mediterranean and who are "living every day with uncertainty".

Without any confirmation of death, families face a traumatic wait, with some believing relatives are still alive and being kept in detention, unable to make contact.

Without any official information, they rely on scraps of news brought back from people who had travelled with their missing relative, or from people smugglers.

"There is a huge emptiness," said one of the families interviewed.