Apple chief Tim Cook's Irish tax claims examined

- Published

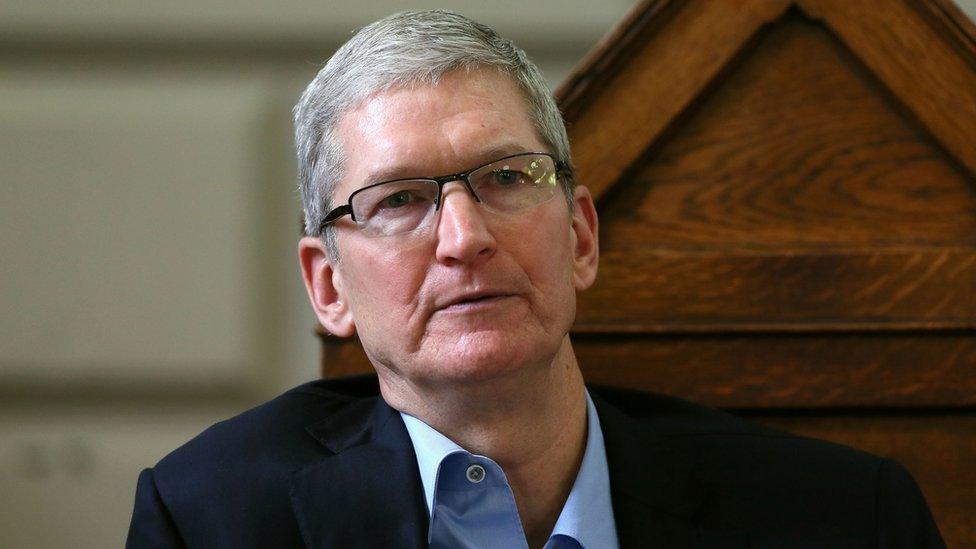

Apple chief executive Tim Cook says the European Commission is "picking on" Ireland and that "no one did anything wrong", but is he right?

In two Irish interviews, Mr Cook hit back at the Commission's "maddening" ruling that Apple's tax benefits in the country are illegal.

He added that the €13bn (£11bn) tax bill Apple received was "political" and based on "false" numbers.

The BBC has looked at some of Mr Cook's key claims to see if they were fair.

Tim Cook's claim: "No one did anything wrong here."

The European Commission would obviously disagree.

Margrethe Vestager, the European Commissioner in charge of the case, stated, external that Ireland's selective tax treatment of Apple was "illegal under EU state aid rules". In other words, under EU law, Apple was given an unfair advantage over other businesses.

Apple has said it will appeal against the ruling to the European Court of Justice, and Ireland's Cabinet is due to decide on Friday if it will also appeal.

It will then be up to the EU's highest judges to decide if Apple and Ireland did anything wrong.

European Commissioner Margrethe Vestager said her ruling was "based on the facts of the case" not politics

The Apple boss's wider point is that the company and Ireland "need to stand together". It is a not-so-subtle reminder of how their fortunes are interlinked ahead of the crucial Cabinet meeting on Friday.

Tim Cook: "Here is the truth. In that year [2014] we paid $400m to Ireland and that amount of money was based on the statutory Irish income tax rate of 12.5%."

Apple says it paid $400m (€360m) in taxes in Ireland in 2014, the year when the European Commission says it paid an effective tax rate on its profits of 0.005%.

However, the question is whether Tim Cook is including different forms of taxation rather than just Irish corporate tax.

The European Commission's investigation - and the 0.005% figure - was focused on the tax paid on profits passing through two Irish subsidiaries. On the vast majority of these profits, the commission found, Apple paid no tax at all.

Instead, much of the profit was attributed to an offshore head office, which BBC Business Editor Simon Jack describes as the "tax equivalent of outer space".

Apple may have paid 12.5% on some profits going through its Irish businesses, but to suggest $400m is equivalent to 12.5% of all Apple's profits that passed through Ireland is far from the truth, the commission would claim.

Tim Cook, CEO, Apple: "It's maddening and disappointing"

Tim Cook: "We believe we're the largest taxpayer there [in Ireland]."

That is plausible - Apple is the world's largest company by market value and does employ about 6,000 workers in Ireland. But the question is whether it is paying its fair share.

We haven't got the details from the European Commission for Apple's total Irish business, but a US investigation found that in 2011 one of the subsidiaries, Apple Sales International, made profits of $22bn (roughly €16bn).

Of this only €50m was considered subject to Ireland's 12.5% tax rate meaning Apple paid less than €10m in tax. If you taxed all $22bn at 12.5%, it would owe more like $2.75bn.

Tim Cook: "Ireland is being picked on and this is unacceptable."

Ireland is not the only country whose tax arrangements with large US multinationals are being investigated by the commission.

Tim Cook said Ireland and Apple were part of a "37-year marriage"

In October 2015, the EU body ordered, external the Netherlands to recover up to €30m from coffee giant Starbucks and told Luxembourg to reclaim the same amount from carmaker Fiat.

Investigations are continuing into whether Luxembourg's tax treatment of McDonald's, external and Amazon, external also amounted to illegal state aid.

Tim Cook: "We actually went into Ireland in 1980. We didn't go there to seek advantage on taxes."

This certainly seems to be the case. Throughout the 1990s Apple manufactured most of the computers it sold across Europe in its factory in Cork.

It still does some assembly of products there, but it is not as important as it once was and Apple's manufacturing is done all over the world now. There is a customer service centre at its Cork base, and plans to expand the factory and open a data centre in Ireland are in the pipeline too.

Irish tax law has changed since 1980 to become more appealing to international companies, but the use of an Irish subsidiary to channel billions of dollars of profits through a lower tax jurisdiction does not appear to be the company's primary reason for opening a base there in 1980.

- Published1 September 2016

- Published30 August 2016

- Published30 August 2016

- Published30 August 2016

- Published30 August 2016

- Published18 July 2018

- Published30 August 2016