The strange story of a seized Hanjin ship and its lonely crew

- Published

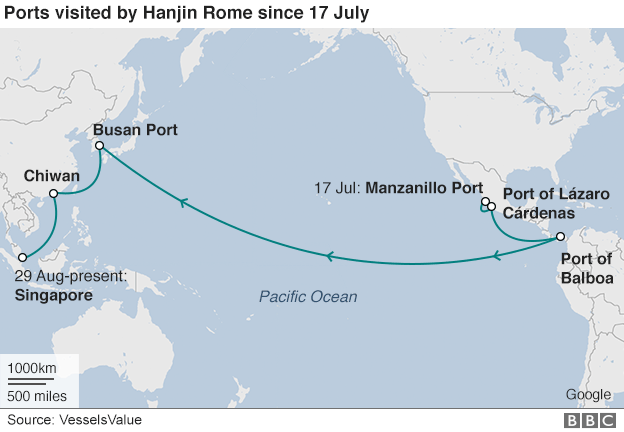

Sprinkled across the oceans around the globe, some 60 of Hanjin Shipping's cargo vessels are stranded at sea after the company filed for bankruptcy two weeks ago.

Here's the story of one of those ships, its captain and its crew.

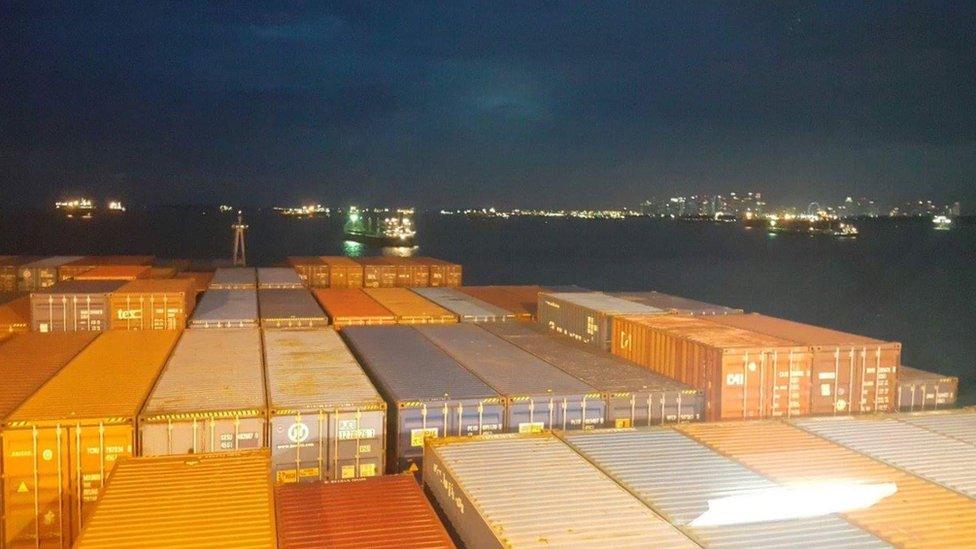

The Hanjin Rome is nestled between countless other ships off the coast of Singapore, a towering container vessel. As with any of these ships, if you approach in a small boat, it seems there's no sign of life up there.

That's what the BBC did, hoping to get on board to see what the situation was. Well, our team didn't get permission - but they did manage to speak to the crew via radio and get some contact details.

The BBC's Sharanjit Leyl hunting for the Hanjin Rome

Since then, I've been spending two days chatting to Captain Moon Kwon-do on Facebook. Without any pressing seafaring duties to attend to, he's got plenty of time to write back and forth and tell me about himself, his men and his "old lady", the Hanjin Rome.

If like me, you don't really know what a modern-day cargo captain looks like, here's a selfie on the bridge:

The sheriff takes control

When the Hanjin Rome arrived in Singapore on 29 August, no-one on board expected anything other than a regular port call. Little did they know that their trip was about to come to a grinding halt.

The previous months had been business as usual - the ship got back from its regular route to South America and was now headed for the Middle East, merely stopping over in Singapore. The usual thing, refuelling, replenishing supplies and maybe picking up some new cargo.

What they didn't know though was that Hanjin Shipping had filed for bankruptcy protection - crumbling under the weight of a staggering $5.4bn (£4.1bn) worth of debt.

"At about 9:20 in the evening, an attorney came on board with a sheriff," Captain Moon says as he recalls the night. The ship got arrested, seized by creditors who were hoping to get at least some money back.

"No-one told me about this beforehand," he goes on, struggling to hide his emotions. The captain was completely left in the dark about the state of affairs.

The 36-year-old was then ordered to go out to an anchorage position and wait. This was two weeks ago - and since then there's been little more information given to them about the ship's - and their own personal - future.

Rough seas ahead?

Missing his wife, his daughter, his grandmother

Captain Moon has a local Sim card brought on board by a friend. A smartphone is his way of connecting with the outside world, whether it's curious BBC reporters, friends, colleagues - or his family back home.

His wife and daughter live in the South Korean port city of Busan, eagerly awaiting any news or development.

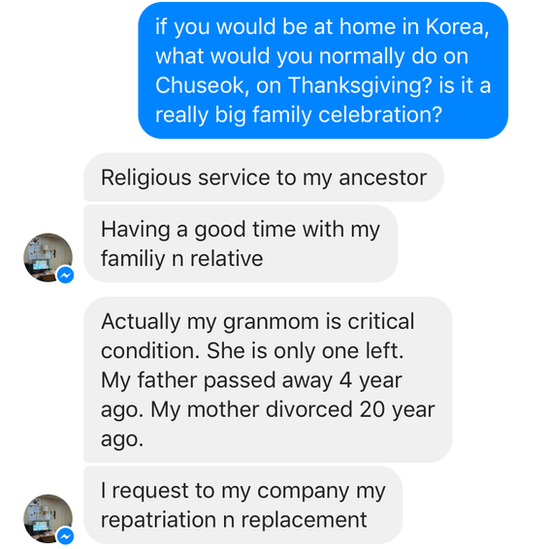

And this Wednesday is not just any day in Korea - it's the beginning of Chuseok, the three-day Korean thanksgiving festival.

It is a day you normally spend with family and relatives, he tells me. It's also important for performing religious memorial services for your ancestors.

In addition, Captain Moon tells me that his elderly grandmother is in a critical condition and that he really wishes he could be back there with her.

He has already asked to be repatriated and replaced as captain - but things are not looking up. "No-one wants to join our arrested Hanjin Rome," he says, sending a sad face emoji on Facebook.

Singapore's not far - but they're not allowed to go there

From my office window, I can clearly see the cluster of ships off the east coast. On one of them, Captain Moon sits typing on his phone. As we chat, one of Singapore's torrential downpours begins. "I like heavy rain," he grins through the internet across the water.

Stuck on board, killing time

Of course he's not the only one missing home and family. There's a total of 24 seamen on board, 11 South Koreans and 13 Indonesians.

I asked for a picture of the crew to get an idea of what a team of 21st Century sailors look like. They sure know how to get their message across.

They are not allowed to go onshore except for things like a medical emergency. But land is temptingly close.

From where they are anchored, Singapore is on one side and a few Indonesian islands are on the other. The Indonesian seamen could almost swim back to their home country.

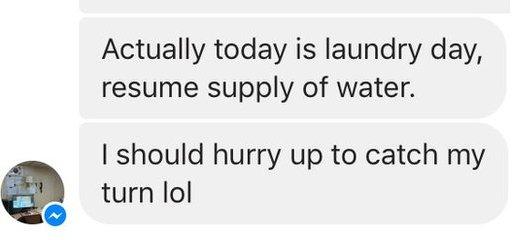

But what to do when you're stuck like they are? I ask him what they're up to all day, assuming they must have heaps of time on their hands.

But I stand corrected, a lot of the work on board has to be done regardless of whether they are sailing or at anchor. Today, in fact is...

Lol indeed - even a captain needs to get his laundry done. So I wait a for a bit and it's not long before he is back online.

In for a lot more laundry days ...

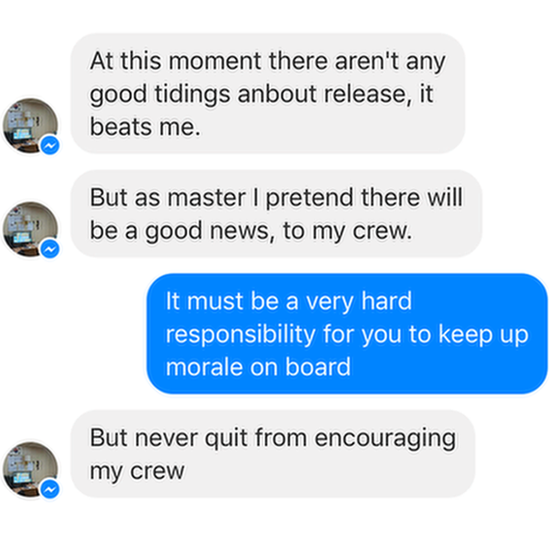

He says that some might regard their situation as "marooned or even abandoned", but that "most crew still have hope this will be settled in the near future".

Shipping lawyers here in Singapore though tell me that it's normal for ships to be arrested for a few months - there are even extreme cases of up to a year.

I ask about water, food, general supplies. They still have enough but stocks are beginning to run low. On Friday, they will get fresh provisions brought on board as well as some entertainment material - movies to watch, games to play.

Maybe also a few more Sim cards so that more of them can get online. For instance, to look for new jobs for when their current ordeal is over.

There is after all little expectation that Hanjin Shipping will survive its current situation.

Night falls and the view is still the same ...

The old lady's very last voyage?

The Hanjin Rome was built in 1998, "an old lady" as the captain says. He's been sailing on her since 2003, and jokes that he therefore has special feelings for her and that "she looks younger than her age".

But good looks won't help her too much in her uncertain future. The ship is one of three built in the late 1990s and in the current shipping drought that means its market value is very low, too low in fact.

"Given Hanjin's extraordinary circumstance, it is probable the three 90s ships will be sold for scrap and sent to the beaches on the Indian subcontinent - the most popular location for scrapping," William Bennett, senior analyst at VesselsValue told the BBC.

The scrap value for the Hanjin Rome is around $7.15m. And as much as Captain Moon likes his old ship, he too agrees that it is probably doomed to be scrapped.

As of now though, the crew remains on duty, officers are manning the bridge 24/7, staring out across the countless vessels anchored around them.

The difference is that the other ships can simply weigh anchor and are free to sail off at any time.

- Published14 September 2016

- Published9 September 2016

- Published8 September 2016

- Published8 September 2016