Why is globalisation under attack?

- Published

A model of a giant snake is held aloft by protesters at an anti-globalisation rally in Berlin

Free trade and globalisation seem to be under siege from a broad and loud range of opponents.

For decades there has been a strong consensus that globalisation brought more jobs, higher wages and lower prices - not just for richer countries but also for developing and poorer nations.

But many people, including politicians, are now voicing their anger as they see jobs being taken by machines, old industries disappearing and waves of migration disturbing the established order.

You don't have to look far to see the effect of those concerns in recent events.

The Brexit referendum was dominated by concerns over immigration, the rise of Donald Trump has brought back the rhetoric of protectionismin the US and there have been mass protests in Europe over prospective international trade deals.

What is behind this backlash and what can be done to address this crisis of globalisation?

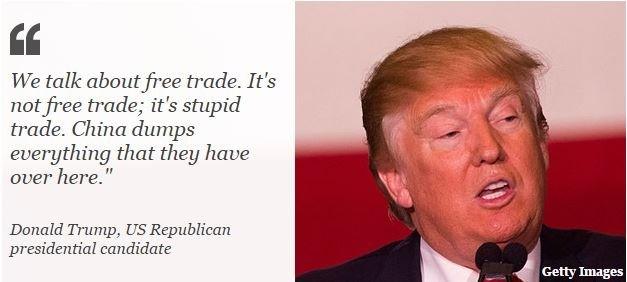

'Free trade is stupid trade'

The US presidential election has felt like the epicentre of the rising tide of disquiet against free trade and globalisation.

Donald Trump has accused China of wanting to "starve" the US population by manipulating their currency and "cheating" on international trade.

He has said he will impose massive tariffs on Chinese goods because it was economically "raping" the US.

Hillary Clinton has found herself surrounded by political challengers questioning the benefits of international trade and globalisation.

Bernie Sanders, Clinton's opponent in the race for the Democratic nomination, defined his campaign by arguing that globalisation had hollowed out the US middle class.

Clinton's response has been to tack towards the concerns expressed by Sanders and Trump, reneging on her previous support of TTIP (the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership) - the trade agreement between the US and Europe.

US manufacturing's decline

Arguments over the decline of manufacturing in the United States have powered a lot of the heat of the 2016 US electoral cycle.

The sense of grievance is clear - the manufacturing sector in the US has seen six million jobs disappear between 1999 and 2011, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The decline in manufacturing jobs has become an issue in the US presidential election campaign

Studies have shown that the decline in the US has been mirrored by gains in China.

Chinese imports explain 44% of the decline in employment in manufacturing in the US between 1990 and 2007, according to a report by the Institute for the Study of Labor in Bonn.

Part of that decline has been down to the outsourcing of jobs to other countries but automation and more efficient processes have also taken their toll.

"All countries end up with losers from technological development - whether it is telephone operators or bank tellers," says Gary Hufbauer, a trade expert from the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

"The problem in the US is that we don't do much to help those people who lose out through social security support or job retraining," says Mr Hufbauer.

Many in the US, Europe and Japan have seen no increase in their household income in the past 10 years

Technological and economic change has hit specific geographical areas that have then found it hard to develop new industries and create jobs.

The anger that flows from this has found a home in the protectionist rhetoric of politicians like Donald Trump.

"There has been no growth in household income during the last decade in Europe, the US and Japan. People are not happy and if you have to blame someone, it is easy to blame foreigners,"' says Mr Hufbauer.

Flat-lining world trade

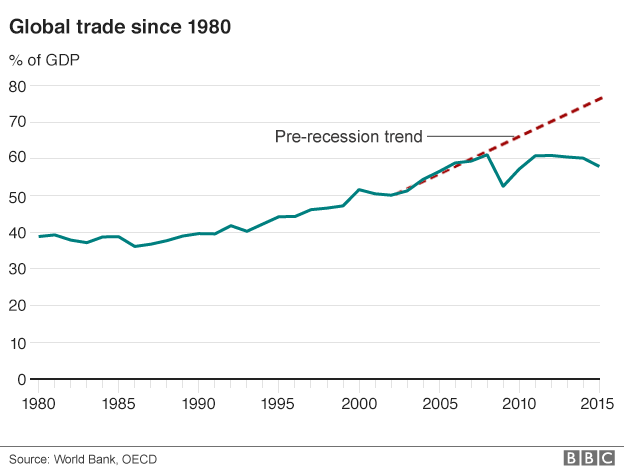

The rise of political opposition to globalisation has coincided with - and contributed to - a period of declining world trade growth since the financial crisis of 2008.

Between 1986 and 2008 world trade grew at an average of 6.5%, according to the World Trade Organization.

Between 2012 and 2015 that rate has slowed to an average of 3.2% and is predicted to expand by just 1.7% in 2016.

That slowdown would make it the longest period of relative trade stagnation since the Second World War.

Since the financial crisis the slowing of the Chinese economy and political and economic stagnation in the eurozone have contributed to this flat-lining of world trade.

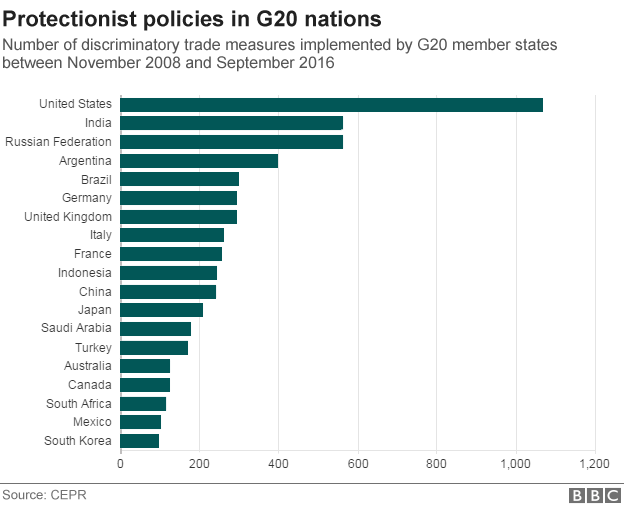

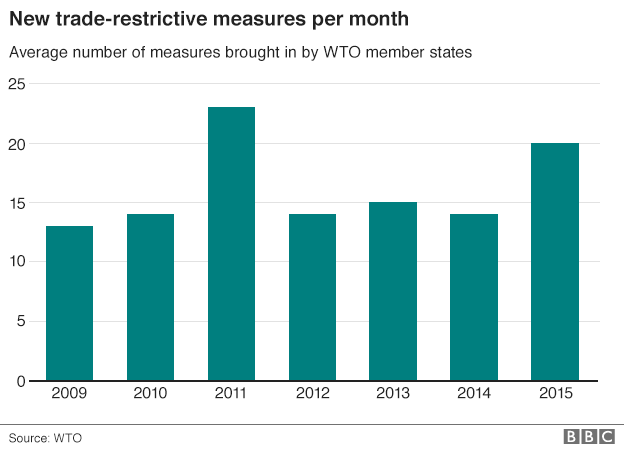

At the same time there has been a steady rise in the application of protectionist measures around the world.

In an attempt to protect companies and industries at home, politicians have turned to tariffs and restrictions on imports from other countries.

"Governments worldwide have almost doubled their resort to trade distortions in the last two years," says Prof Simon Evenett, a trade expert at St Gallen University.

"The recent surge in 'beggar-thy-neighbour' activity predates Trump and Brexit, suggesting that populist pressures are likely to exacerbate protectionism," he says.

Economists warn that while protectionism may seem appealing to politicians assailed by angry workers, they in fact only end up raising prices for consumers.

There was an outcry in 2012 when cheap Chinese tyres flooded into the US market, putting the viability of the domestic producers in question.

President Obama responded with punitive tariffs to get China "to play by the rules".

The protectionist measures were well received in the US, but a study by the Peterson Institute established that the tariffs meant US consumers paid $1.1bn more for their tyres in 2011.

Each job that was saved effectively cost $900,000 with very little of that reaching the pockets of the workers.

Free trade fightback?

With the economic and social benefits of free trade coming increasingly under attack, proponents of globalisation have tried to launch a counterattack.

"For six decades after the Second World War, unprecedented growth of trade in goods and services and spectacular expansion of foreign direct investment were powerful drivers of the best half-century in human history," says Gary Hufbauer.

The World Bank, World Trade Organization and International Monetary Fund have made the issue a central part of their meetings in Washington DC this week.

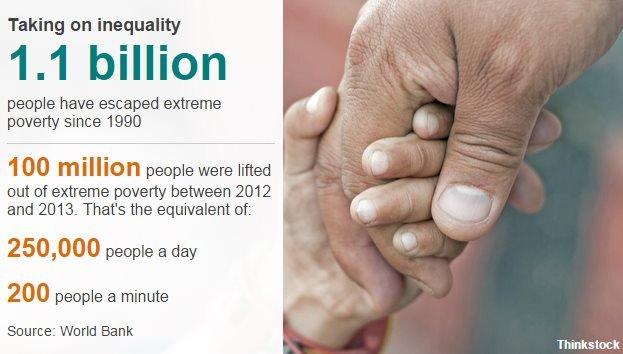

To emphasise the point, the World Bank has brought out a study of developing countries that shows that average incomes for people living in the bottom 40% increased between 2008 and 2013, despite the impact of the financial crisis.

There also seems to be a realisation amongst politicians that income inequality and economic stagnation, whatever the cause, is an issue that must be addressed.

"I think there is a realisation in rich countries and among rich elites that there are problems with globalisation," says Branko Milanovic, an economist whose work on income inequality has driven much of the debate.

"They realise that for their own political self-preservation they have to tackle them."

The problems that flow from this discontent may have been diagnosed but the solutions are not obvious, nor easy to implement.

Critics argue that the benefits of globalisation have been shared by only a few in many societies

"Most of the benefits of globalisation have been enjoyed by a relatively small group within each country," says Andrew Lang from the London School of Economics.

"The question is not whether there are benefits to globalisation - there clearly are. But the question is about who is enjoying those benefits," says Prof Lang.

Part of the anger might dissipate if economic growth was to stop its stubborn flat-lining trajectory, lifting incomes around the world.

"To help solve these problems you need to get the world economy revved up. Governments need to commit to fiscal stimulus to get their economies going again," says Gary Hufbauer.

Branko Milanovic points to the success of previous politicians in turning round seemingly intractably weak economies.

"It's not impossible for politicians to address these issues," he says.

"Thatcher and Reagan managed to effect change in relatively short periods of time - a presidential term of four years should be enough to start making a difference."

Criticism from right and left

The opponents of globalisation and world trade feel their movement is making inroads.

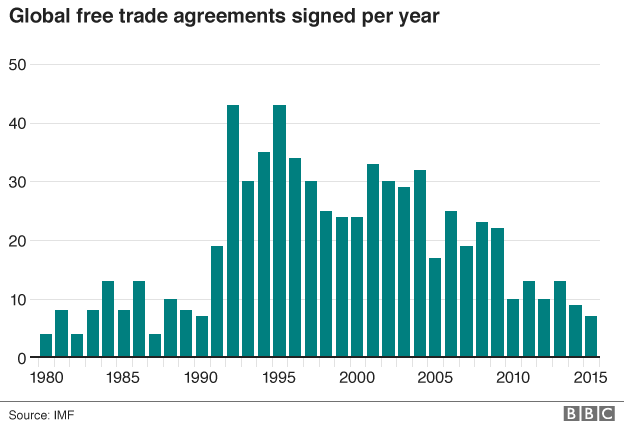

The TTIP negotiations seem to have ground to a halt, the US election has thrown the future of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) deal into question and the number of new free trade agreements has fallen.

There is a broad chorus of disquiet emphasising opposition to the old consensus of free trade.

With voices from the political right and left raising questions about the benefits of globalisation, there is a broad base of discontent

Globalisation may be under assault from all sides but its proponents insist its revival is the only way of alleviating the discontent that now fuels its unpopularity.

Find out more

The BBC is reporting from around the world on the impact of globalisation on people's lives and on the growing movement against free trade, with special coverage on TV, radio and online.