How Sunderland defied Nissan's boss

- Published

Nissan boss: 10% tariffs would be 'handicap' for Sunderland plant

When Carlos Ghosn made his not-very-veiled threat about the future of the giant Nissan plant in Sunderland last week, he might have thought locals would have quailed and rallied to his cause.

He has longer to wait.

People in Sunderland don't always do as they are told; before the vote on Britain's membership of the European Union, the Nissan chief executive urged people to vote to remain, stressing the advantages to Nissan, the region's biggest employer, of staying in the single market.

They ignored him, with just under two-thirds of the Sunderland electorate voting to leave.

Paul Watson, Labour and Co-operative leader of the city council since 2008, says people value Nissan's contribution to the local economy - it is the region's largest employer, providing work for 7,000 people - but that Sunderland is used to the vagaries of the world economy having big effects at home.

The coal industry here powered the empire, employing hundreds of thousands to work the Durham field in scores of pits.

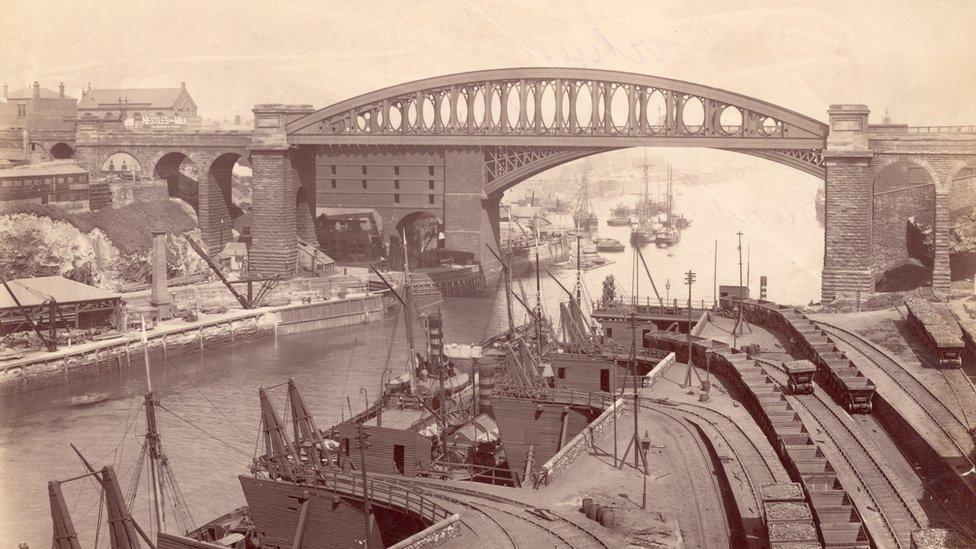

Sunderland Bridge and Lambton coal drops on the River Wear, circa 1880.

The industry still shapes the local culture; Washington, the new town beside the Nissan plant, remains in reality an amalgamation of about a dozen pit villages, where people still identify with their immediate area rather than the wider north east.

When the pits closed in the 1980s - a victim of high costs relative to imported coal and a protracted battle for supremacy between mining unions and the Thatcher government - people learned the hard way that the tide of global commerce can go out quickly.

In Washington, they do not bemoan the loss of the pits themselves, as they brought their own horrible legacy of occupational diseases, but they rue the lack of something to replace them.

Shipbuilding was Sunderland's other great loss. At one stage the River Wear, which divides the city, could boast that it accounted for one-quarter of the world's new ships. Only 50 years ago it was still an international force, but now there are few signs the industry ever existed.

'Still making things'

Mr Watson says the real dark days for Sunderland - the 1980s, when the town reeled under the combined closures of pits and shipyards - are now behind it. The economy has been reinvented, with call centres, Nissan and now a burgeoning tech scene picking up the slack.

"The big monolithic industries have gone," said Mr Watson, who once worked in a shipyard, "but other things have come in. It is about having a strategy, and our strategy is simply to make Sunderland prosperous."

At Sunderland Software City, a tech hub that would not be out of place in London's Silicon Roundabout, part of that vision is coming true. There are special effects firms, web designers and games makers.

David Van der Velde, managing director of Consult and Design, a digital agency based in the centre, says people in the North East have a natural inventiveness that lends itself to technology companies.

"Sunderland has always been a place where people make things, people are inventive. We've moved from making things out of steel to making things out of software, but we're still making things"

- Published9 August 2016

- Published29 September 2016

- Published3 October 2016