What does Uber employment ruling mean?

- Published

Two Uber drivers take opposing views on how the company should treat them

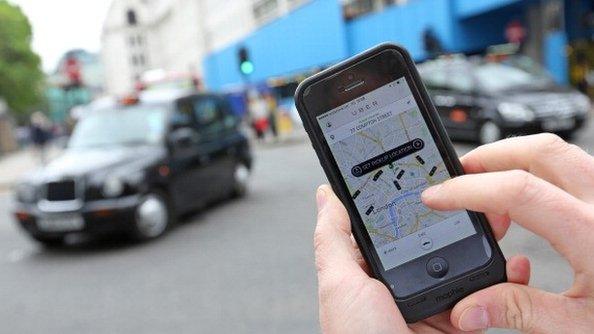

An employment tribunal in London has ruled that Uber drivers can be classed as workers - and are not self-employed.

Two Uber drivers claimed the company was acting unlawfully by not paying holiday or sick pay.

It has been described as a test case not only for the business model of ride-hailing firm Uber, but for the whole so-called "gig economy".

Uber insists its drivers are self-employed and says it will appeal.

The firm has more than 40,000 licensed drivers in 20 UK towns and cities making more than a million trips per week.

Drivers and campaigners hail Uber ruling

The outcome of this case may not only affect its business model, but could also change the relationship between many firms and their self-employed workers.

What did the drivers say?

Two drivers, James Farrar and Yaseen Aslam, argued that they were employed by Uber but didn't have basic workers' rights. The cases were brought by the GMB union.

The drivers said they should be entitled to holiday pay, and that they should be paid the National Minimum Wage.

For example, Mr Farrar (who no longer drives for Uber) said his net earnings in August 2015 after expenses were £5.03 an hour.

The drivers also argued that their actions were controlled by Uber, so in effect they were employed by the firm.

Uber has insisted that drivers are self-employed

Once a driver accepts a job he or she is not notified of the destination, and faces punitive measures if they don't perform well enough, for example, following a customer complaint.

The two drivers claimed sums of money were frequently deducted from their pay, often without advance warning.

A further 17 claims have been brought against Uber, according to law firm Leigh Day, external.

What did Uber say?

Uber argued that there are more than 30,000 drivers in London and 40,000 in the UK using its app to find customers. Many do so, it says, because it allows them to work flexibly.

The firm says drivers, whom it calls "partners", can "become their own boss".

It also doesn't set shifts or minimum hours, or make drivers work exclusively for Uber.

The case could have huge implications for employment law, says lawyers

Uber said that in September, drivers for UberX (the most basic private car service that Uber offers) made £16 an hour on average, after Uber's service fee, and that only 25% logged in for 40 or more hours per week.

What is at stake?

Alex Bearman, partner at law firm Russell-Cooke, says the outcome is likely to have "significant implications for other operators in the fast growing 'gig economy'".

Similar cases are currently being brought against the courier firms CitySprint, eCourier and Excel as well as taxi firm Addison Lee.

But Martin Warren, partner and head of labour relations at Eversheds, says the fact the Uber claimants have won their case does not mean that cases brought by others will have the same success.

"Each case will depend on the specific terms and arrangements between the individual and the company they work for."

Black cab drivers have protested against Uber

What does this mean for Uber?

Uber is appealing against the decision, but it may have to give drivers back-pay for unpaid benefits in the UK, and pick up the future cost of those benefits.

"We may not see a final determination for some time to come," says Mr Bearman.

Will fares go up?

They may have to, as Uber may pass on any higher labour costs to its customers. "Consumers will see prices rise and a less stable, predictable service," believes Sam Dumitriu, head of projects at the Adam Smith Institute.

Luke Bowery, a partner at Burges Salmon agrees. "[Higher fares will] disrupt Uber's ability to offer a flexible and responsive service to its customers - potentially hitting at the heart of service delivery, as well as its profit margins," he says.

Could the ruling affect Uber outside the UK?

The ruling applies only in the UK. Different countries have different employment laws.

However, the tribunal's decision "may have an impact on how Uber operates in other countries and we have already seen similar significant claims from drivers being settled in the US," Mr Bowery says.

What happens to the 'gig economy'?

The trend of firms taking on self-employed workers who engage with work through apps may have to change radically, says Mr Bowery.

Faced with similar employment tribunal claims, these firms may either have to change their business models, or pass the increased costs onto customers.

"When operated in the right way, many individuals, including some Uber drivers, highly value the benefits the gig economy can bring," adds Mr Bowery.

"These benefits do need to be balanced, however, against potential exploitation and we are unlikely to have seen the last of claims of this type as the gig economy continues to grow."

- Published28 October 2016

- Published28 October 2016

- Published28 October 2016

- Published12 October 2016

- Published20 July 2016