Coal country West Virginia feels forgotten by politics

- Published

The tree-filled Appalachian mountains of West Virginia are home to America's coal region

The vacant store fronts of low buildings line Delbarton's main street. A town once thriving on money from the coal industry is now fighting for its existence.

Delbarton is typical of many towns in West Virginia, built on coal and suffering as the industry shrinks.

Former miner Bo Copley knows this struggle firsthand.

In September 2015 he was laid off from his job at a coal mine.

He is one of nearly 200,000 people who have lost their jobs in the coal industry since September 2014.

The layoffs have increased an existing rift between West Virginia's population and Washington DC politicians - who they feel don't care about the state's unique culture and struggles.

Bo Copley: "It's pretty personal here"

In May, Mr Copley brought this anger directly to a meeting with the Democratic presidential candidate, Hillary Clinton.

The roundtable between Mrs Clinton and members of West Virginia's coal community gained international attention, external when Mr Copley, 40, took out a picture of his three young children and asked the candidate to explain her remarks that she would "put a lot of coal miners and coal companies out of business".

Mrs Clinton responded by saying her comments had been taken out of context but acknowledged it had been a "misstatement".

Towns in the south-west of the state are struggling as the coal industry falters

"Everything in communities like Delbarton is related to coal," Mr Copley told the BBC.

"For every coal job you [lose] here, you have five, maybe seven jobs you eventually will lose in the whole economic background of this state."

Politicians don't get it

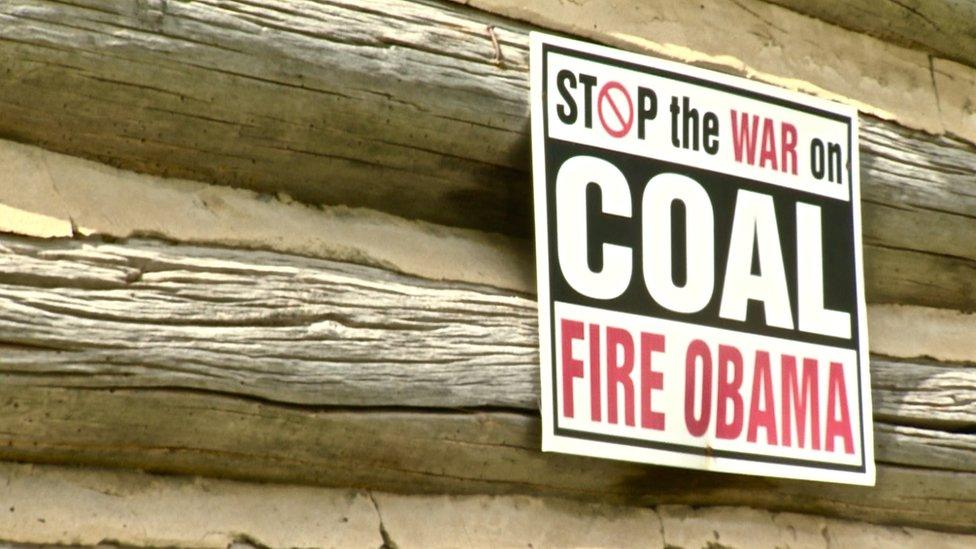

The anger in West Virginia isn't reserved solely for Mrs Clinton. Many blame President Obama's "War on Coal" for excess regulation resulting in mine closures.

Donald Trump's promise to revive the coal industry has been well received, though many in the region doubt he can return it to its peak.

Between 2008 and 2015 coal production in south-western West Virginia, the state's main mining region, dropped 50%.

President Obama's "War on Coal" has found few friends in West Virginia

While environmental restrictions have increased pressure on coal production, market forces - including cheap natural gas and increasing mechanisation - are also squeezing the industry and forcing job cuts.

Employment in the sector is at its lowest level in over a decade. It fell from close to 26,000 at the end of 2011 to just over 16,900 by the middle of 2015.

From mining to farming

One of those who lost his job was David Green. He was laid off in April after working in the coal industry for 23 years.

Now 50-year-old Mr Green has become a full-time farmer. He grew up farming and said that before being laid off he already produced nearly all the food he and his wife ate.

After losing his job he began renting a larger plot of land and selling his produce at a farm-stand and weekly farmers market.

In November he plans to open a meat-processing facility to butcher the deer caught locally.

Despite his expansion plans Mr Green says he would go back to mining if he got the chance.

"The mines are for the money and the guaranteed money," he says. "[It's a] little risky, but it's real good money."

David Green turned to farming full-ime after losing his job in the coal industry

For Mr Green neither presidential candidate presents a great choice, but he sees Donald Trump as the lesser of two evils.

"Neither one of them in my opinion [is] good for the coal industry, but Trump will be way better than Hillary because he likes to see business and he wants to see revenue for all the states," says Mr Green.

West Virginia used to be a stronghold for the Democratic Party, which could rely on the votes of union members. But the party hasn't won the state in a presidential election since Bill Clinton in 1996.

Part of the challenge for all politicians is the general feeling that West Virginia has been forgotten by Washington. It is part of the reason political outsiders like Donald Trump have done so well there.

Environmental campaigner Maria Gunnoe would like to vote for the Green Party candidate, Jill Stein

"You can't expect politicians to fix everything in West Virginia because politics is what caused the problems in West Virginia," says Maria Gunnoe, an environmental activist.

Ms Gunnoe, 48, does not plan to vote for Mr Trump. She says she would like to vote for the Green Party candidate, Jill Stein, but is afraid that could help hand Mr Trump victory.

'Owed something more'

Ms Gunnoe has spent nearly half her life fighting against mountain top removal (MTR) - a process that blasts away rock to reveal hard-to-reach coal seams.

She blames an MTR site near her home for flooding and landslides on her property.

Maria Gunnoe's home has suffered flooding and landslide damage several times

Although she does not want to see a revival of the coal industry, Ms Gunnoe does have one thing in common with the miners: she blames a national indifference for many of West Virginia's problems.

"We built this country from the coal that's been mined out of the ground, that has made the steel and powered this country, and we are owed something back and we are owed something more than the pollution and the poverty," she says.

As the election draws to a close many West Virginians are hoping the outcome will mean a fresh start. But few think quick changes will come - regardless of who is the next president.

- Published31 October 2016

- Published26 October 2016

- Published3 October 2016