How to keep house prices low for generations to come

- Published

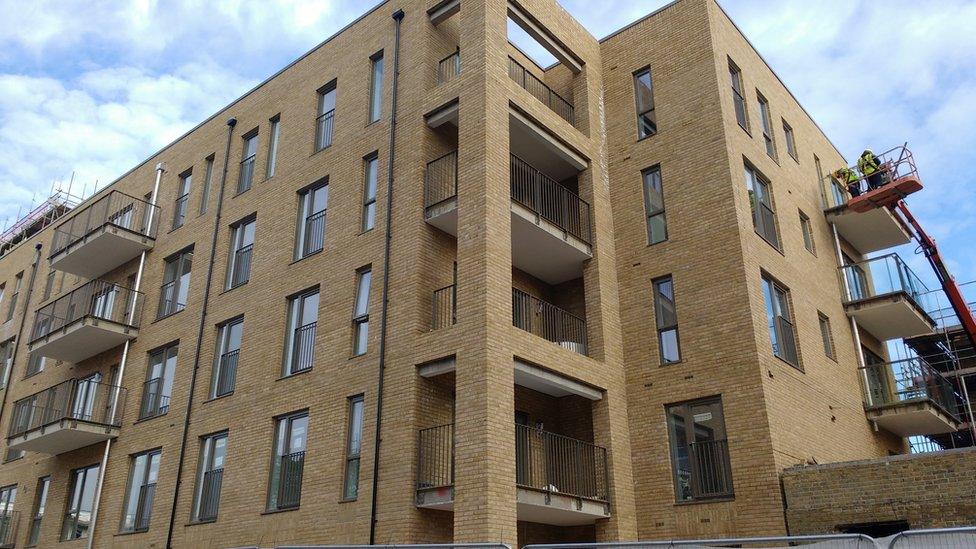

The Evans family is buying a flat that will remain cheap for years to come

Imagine a world in which the price of housing stopped rising as predictably as a hydrogen-filled balloon.

And imagine a country in which houses would be just as affordable in 10 years' time as they were 10 years ago.

There would be no race to buy a home, no fear that prices would accelerate faster than you can save up for the deposit.

Houses would cease to be a means of profit, and instead become just a place to live.

But this is no John Lennon-inspired fantasy.

It is about to come to fruition in the East End of London, in an extraordinary experiment.

For the first time, future property prices will be tied to the rise in wages.

'Life changing'

In a couple of weeks the first of 23 families will move in to an old mental health hospital in Tower Hamlets that has been converted into flats. They will pay a third of market value.

When they come to sell, the price they are allowed to charge will be limited by the increase in local wages, as measured by the Office for National Statistics.

Amongst the buyers are Rachael and Nathaniel Evans and their young son Griffin.

Property in the Tower Hamlets area has become unaffordable for most

Despite their joint income of £33,000, and savings of nearly £70,000, they have been unable to afford anything in the area.

But now, thanks to the local Community Land Trust (CLT), they will soon be moving into a home of their own.

"It is amazing. It is life-changing for us," says Nathaniel, who has lived in Tower Hamlets all his life.

"I imagine walking into the flat and thinking, 'this is ours,' and we don't have to leave."

Link to wages

But the wage link is significant.

When Rachael and Nathaniel eventually decide to sell, their property's value will not have gone up in line with the market.

Typically, wages have risen by less than 2% a year over the last decade, dipping as low as 0.7% as recently as June 2014.

At the same time, despite a few dips, house prices have soared by up to 9%, easily outpacing wages.

If that trend continues, the relative value of their flat will decline, making it hard for them to move elsewhere.

As a result, linking house prices to wages requires a very different attitude, says Calum Green, co-director of the London CLT.

"These homes should be considered homes, not assets," he tells the BBC.

"It should be a place where you want to live for many, many years. It's not all about ladders and working your way up."

The block where the Evans family is buying a flat

In any case Rachael believes the security of owning a home is more important than its value.

"It's not so much about how much money we're going to make out of this, it's that we're not going to get a letter through the post next week saying we've got two months to leave."

And there is one financial compensation: the mortgage the couple will pay on their flat will be lower than the £1,000 a month rent they were paying previously.

"That will give us the opportunity to save a little bit each month," says Nathaniel.

"And to prepare for the day - if ever it comes - when we move out, and house prices have risen around us."

How does a Community Land Trust Work?

CLTs exist to provide affordable homes, both for rent and for purchase. There are 175 CLTs in England and Wales, which so far have delivered 560 homes.

In some cases land for development is given to CLTs, free of charge, by a local authority for example. In other cases CLTs may work with developers, who donate the freehold to the CLT after they have made their profits.

More frequently, CLTs buy the land themselves.

In Scotland the focus has been more on the community ownership of land, rather than homes, after the law was changed to allow residents to buy land that comes up for sale.

'Crewing the lifeboat'

Most CLTs are actually in rural areas rather than urban ones.

Typically, they have been set up where local house prices have risen far above what residents can afford.

One example is at Rock, in north Cornwall, where second home-owners have moved in to enjoy the beaches and the sailing, so inflating prices.

After a local farmer donated the first bit of land, residents got together to build their own homes on it.

So far 24 have been completed, with others in the pipeline.

CLT homes in Rock, which are worth less than a third of their open market value

While future prices are not linked to wages, their re-sale value is limited to 31.3% of what it would be on the open market, ensuring future affordability.

"That way," says Ted Rowe, the chairman of the St Minver CLT, "the village can keep the young people who crew the lifeboat, and the older ones who staff the coastguard."

The government is expected to announce a programme of support for similar coastal and rural CLTs in the Autumn Statement.

It will be funded out of the extra stamp duty chargeable on second homes.

Change of thinking

Critics say that CLTs are not a solution to the UK's housing crisis, as they can only ever build a relatively small number of properties.

They also often rely on land being given away for free, or at a discount.

"Access to land is the real issue," says Luke Murphy, a senior research fellow in housing policy at the Institute for Public Policy and Research (IPPR).

"So scaling it up in the absence of a supply of land - that's where the idea may face some difficulties."

But perhaps more than that, it requires a redefinition of why we aspire to own a home in the first place.

Is it because we want somewhere to live, or is it really because we want to make money?

"The reason why people in Britain want to own their own home, I think, is because that's the only way you can get security," says Calum Green.

Because of that, Luke Murphy believes CLTs which link prices directly to wages could really catch on.

"Yes, you will forego the increase in your own assets, but it does bring the other benefits of home ownership: security, being able to put down roots in your own community, and control over your environment."

For a generation of parents who were able to afford a home themselves, but who know guiltily that their children will never be able to do so, the idea also provides some hope.

As Calum Green says, "We need to lock affordability in, so it's not just beneficial for one family, but it's beneficial for generations to come."