The firms turning poo into profit

- Published

Poo is not something most people like to talk about. Yet it's something we all produce a lot of.

In fact, on average each of us generates 135 to 180 litres of sewage a day - an estimate that includes the waste water from our baths, sinks and washing machines as well as faeces and urine.

Treating and dealing with it is an expensive and time-consuming business. Yet instead of seeing human excrement as something to get rid of, some firms are now managing to turn it into something useful and even profitable.

Northumbrian Water is one company that is now a recognised expert in the use of what it calls "poo power" - using human waste to generate gas and electricity.

The water firm was the first in the UK to use all its sludge - the goo generated after raw sewage has been treated - to produce renewable power.

And as Richard Murray, head of waste water treatment at the firm, says, recycling was "not at the forefront of everyone's mind" in the 1990s. "We just wanted waste to disappear," he says.

It was a chance meeting in 1996 with a Norwegian firm that was converting its sludge into energy that triggered Northumbrian's change of heart.

Crucially, says Mr Murray, the process meant turning sludge from "a cost to something that gave us a bit of income".

"It changed our whole look on sludge."

Northumbrian Water spent £70m on two advanced anaerobic digestion plants, helped by government incentives

Northumbrian now uses anaerobic digestion to capture the methane and carbon dioxide released by bacteria, digesting the sludge and uses it to drive its gas engines to create electricity. It also injects some gas directly into the grid.

It has two biogas plants, which together have reduced the firm's annual £40m electricity bill by around 20%. In total, Mr Murray estimates it has saved the firm £15m a year.

Rival UK water firms such as Severn Trent and Wessex Water are doing similar things to Northumbrian, and biogas production is common in countries such as China, Sweden and Germany.

'Deeply cultural'

On a global scale such processes have enormous potential.

If all of the world's human waste were to be collected and used for biogas generation, the potential value could be as high as $9.5bn or enough to supply the electricity for 138 million households - around all of Indonesia, Brazil and Ethiopia combined, the United Nations has calculated, external.

But despite the obvious financial and environmental advantages, it warns this may not be sufficient to overcome what it calls the "ick" factor of using our own waste.

Sarah Jewitt, an associate professor of geography at the University of Nottingham who has researched different attitudes to human waste globally, says the "barriers are deeply cultural".

"Poo is never very nice in any society. There are really strong cultural attitudes to what's acceptable and what people contemplate," she says.

She notes that while in the UK toilets and sewage systems mean we think little of the potential health risks connected to excrement, in the developing world there's little such certainty.

Janicki Bioenergy says its local crew have been "excited to try" the water produced from sewage

Poor sanitation in the developing world kills 700,000 children each year. Improving this is what drove the creation of the Janicki Omni Processor.

The machine, created by US engineering firm Janicki Bioenergy, converts sewage into drinking water and electricity, while creating ash as a by-product.

The firm's pilot project is in Dakar, Senegal, and can now treat the waste of 50,000-100,000 people. Its water was declared "delicious" by Bill Gates who has funded it through his foundation.

'New lessons'

Despite obvious fears that people may be wary of actually drinking the water, the firm says its local crew have been "excited to try it". "In fact, they voluntarily drink the water on a regular basis as the practice has actually become quite popular," it says.

Sara Van Tassel, the firm's president, says they are "continuing to learn new lessons with every month of testing", working out how to deal with things such as dust storms, finding spare parts and maintenance.

She says the experience has been "invaluable" to its commercial model, the first unit of which it plans to ship to West Africa next year.

Its hope is that eventually there will be several of these machines around the world, each expected to process the waste of up to 200,000 people, and provide water for 35,000.

A single passenger's annual food and sewage waste can fuel a Bio-Bus for 37 miles (60km)

But pilots don't always go to plan. The UK's first "poo bus", running on human and household waste on the aptly named number two route, was launched with much fanfare in Bristol last year.

The initiative was led by Wessex Water's renewable energy company GENeco to show how biomethane gas - produced during the treatment of sewage and inedible food - could be used as a sustainable alternative to traditional fossil fuels to power vehicles and homes.

Yet despite the bus receiving positive reactions from passengers and being praised by environmental organisations, First Group, which operated the bus, said its government application to expand the service was unsuccessful.

The gas produced by Bristol sewage treatment works is now instead injected into the national gas network.

Previous research suggested the waste from one million Americans could contain as much as $13m worth of metals per year

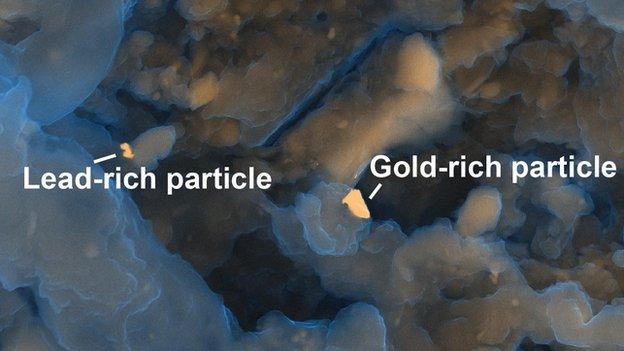

In the meantime, there's always poo mining. Brave US researchers last year identified gold in waste from American sewage treatment plants at levels which, if found in rock, would be considered worth mining.

The researchers also found silver, and rare elements including palladium and vanadium.

A previous study, external, by Arizona State University, estimated that a city of one million inhabitants flushed about $13m (£8.7m) worth of precious metals down toilets and sewer drains each year.

Pooh-poohing ideas about poo may be unwise.

- Published10 November 2016

- Published6 April 2016

- Published11 May 2016