Reality Check: How much will Brexit cost?

- Published

The claim: The Office for Budget Responsibility predicts that the government will have to borrow an extra £58.7bn as a result of the UK's vote to leave the European Union, a forecast that is too gloomy according to some commentators.

Reality Check verdict: All forecasts are uncertain. The OBR is predicting a considerable amount of extra government borrowing as a result of the vote to leave the European Union, but its overall forecast is more optimistic than the Bank of England and the average of independent forecasters.

Much of the gloominess comes in the early years of the forecast, which are likely to be more reliable than later years. The OBR has a record of being too optimistic in its borrowing forecasts, especially in the later years of its forecasts.

It is no surprise that the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) said that the vote to leave the European Union would mean the UK economy would grow less and the government would have to borrow more.

The OBR uses much the same forecasting methods as were used by the overwhelming majority of economists who warned during the campaign that the vote to leave would be bad for the economy.

The £58.7bn extra that the OBR predicted, external would have to be borrowed by the end of 2020-21 is broken down into five parts:

Lower migration

Lower productivity growth

A cyclical slowdown

Higher inflation

Lower interest rates

Of those, the lower interest rates are good for the economy, while the other four are bad.

The OBR was given extracts from two of the prime minister's speeches to guide it on the government's policy on Brexit.

They included the line "we are not leaving the European Union only to give up control of immigration again" so it is not unreasonable for the OBR to think migration would be lower as a result of the Brexit vote.

Orthodox economic thinking is that migration, and especially new migration, is good for the economy.

Slower productivity growth is based on uncertainty surrounding the process of Brexit leading to lower investment by companies.

The cyclical slowdown also comes from uncertainty hitting investment by businesses and higher inflation hitting the spending power of consumers.

Higher inflation is caused by the weaker pound increasing the cost of imports.

Professor Sir Steve Nickell, one of the three heads of the OBR, said at its press conference: "In so far as our forecast is gloomy it's based on stuff that's already happened.

"The exchange rate has already fallen and that is the key to our forecast of weakness in the economy next year.

"Investment growth is already being lower this year than it was last year."

So the OBR forecast is broadly based on what has happened so far continuing to happen, which is not unreasonable, and that is why the OBR finds a negative effect from the Brexit vote.

Inexact science

Is it too optimistic or too pessimistic? The OBR is forced to put numbers to these things - that is its job - and it is important to the government that it does so in order that it can have a central idea of what its current policies will do to the economy.

The OBR's forecasts are based on the same sort of economic modelling that we talked about during the referendum campaign. It is not an exact science and it gets less precise the further in the future you look.

The OBR is very open in this set of forecasts in warning that the later years of the predictions are particularly sketchy, because it does not know what sort of deal will be done governing the UK's future relationship with the EU.

It assumes that Brexit will happen at the end of March 2019 because that is government policy, but predicting what will happen in the two years after that is almost impossible.

Interestingly, it is in the two years before Brexit that the reductions in the forecasts for economic growth happen - there has been no change to the forecasts for 2019 and 2020.

The editor of the Spectator, Fraser Nelson, said on BBC Radio 4's Today programme: "Even the growth is expected to get back to normal in 2019 and 2020 so the idea of an enduring Brexit-related lag on growth isn't taken seriously by the OBR."

That's not quite right - the two years of slower growth would represent an enduring Brexit-related lag - growth is indeed permanently lower.

But the point is that the gloomy bits of the forecast come in the early years, based on the assumption that things already happening will continue to happen.

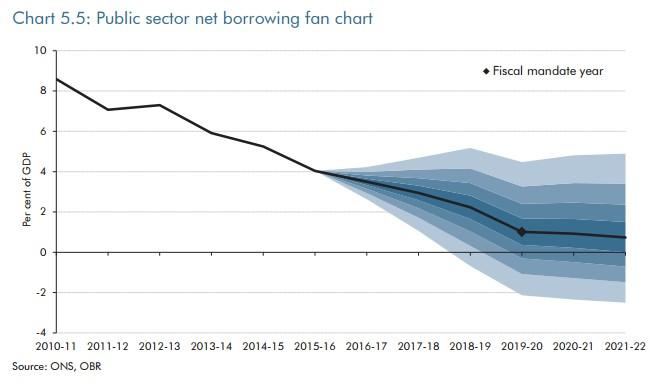

It may turn out to be too gloomy - the £58.7bn of extra borrowing is the central point of the forecast. The OBR publishes fan charts to illustrate this.

Fan charts illustrate the probability attached to parts of the forecast. The darker the colour the more likely an outcome. Each level of shading represents a 10% probability, with a 10% chance of the outcome being completely outside the fan.

So, for example, there is still a 35% chance that the government will balance the budget in 2019-20. On the other hand, the outcome could be considerably worse than the OBR has predicted.

The OBR's forecasts are slightly less gloomy than those of the Bank of England, more optimistic than independent forecasters, external in 2017, 2018 and 2019 and considerably less gloomy than those of the Treasury during the referendum campaign.

The OBR, like other forecasters, has not been right every time. But if anything, its forecasts have been too optimistic, especially in the later years of its forecast periods.

In its first set of forecasts for the June 2010 Budget,, external for example, it predicted that the deficit in 2015-16 would be £20bn. It was actually £76bn.

- Published24 November 2016

- Published23 November 2016

- Published17 November 2016