Could your unused space make you money?

- Published

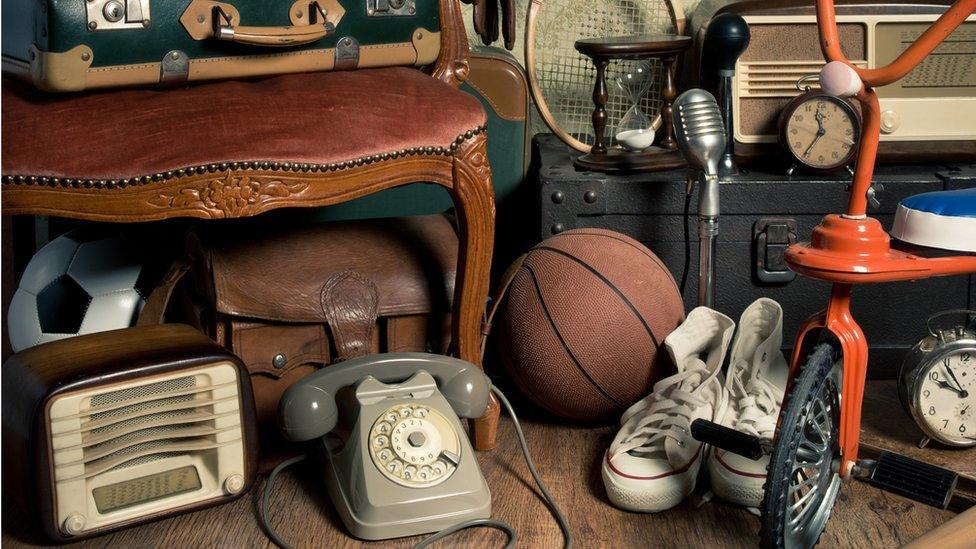

Why not use your spare attic space to make a bit of money?

When he split up with his girlfriend, Anthony Paine needed to store his stuff somewhere fast.

As he shut the door of their flat for the final time, the irony struck him that there must be lots of people with space to spare nearby, if only he could connect with them.

So he and his business partner David Mantle began their mission to create a kind of Airbnb for storage.

The result was Stashbee, external, a company that links people with spare garage and attic space with those looking for cheap storage.

It is one of a growing number of storage start-ups worldwide testing the boundaries of the tech-fuelled sharing economy.

But how does it work in practice?

I'm renovating my house and need to store three boxed items, a bag and a set of golf clubs. So I decide to give Stashbee a try.

The website connects me with Rowena who lives near me and has more attic storage space than I can dream of.

Social storage: The people profiting from surplus space

"I'm a great believer in the sharing economy," she says, after we've hoisted my stuff into her loft. "It's great that resources that aren't being used full time are being used more widely."

Does it feel weird having a stranger's stuff in your house, though?

"You have the right to pull out on meeting the person," she replies. "If my instincts were going 'eeuugh', I wouldn't go ahead with it."

Thankfully, I passed her test. To store my stuff with Rowena for two months costs £56.

The traditional self-storage industry is worth £440m a year in the UK, external and more than $20bn (£16bn) in the US, dominated by established companies like Public Storage, external and Big Yellow, external.

Can storage start-ups also win our trust?

Can storage start-ups draw people away from traditional warehouse storage services?

Carlos Sousa, a sales manager with Access Self Storage, external, a national self-storage firm in the UK, is sceptical about storing with "amateurs".

"Here you have access to your goods 24/7," he tells me, as he opens up a typical locker in the basement.

"If you share with a stranger there's no guarantee they are going to be home when you need your stuff."

Storing my same stuff at a warehouse like this in London costs around £75 - with long-term costs creeping up afterwards.

And he questions their security arrangements too.

Rowena says the sharing economy is a lot to do with trust and personal rapport

The big problem, argues Stashbee's David Mantle, is that people are taught from childhood to distrust strangers. The sharing economy forces us to overcome this training, he says, and recognise that most strangers don't want to harm us.

This is why, unlike rivals, his site prioritises hosts' profile pictures as opposed to pictures of the storage spaces. Like a dating site, it's about that first, human impression, Mr Mantle believes.

He confirms that Rowena could have pulled out if she didn't like me. And for customer peace of mind, they perform background checks on hosts. And they have just organised an opt-in insurance policy to cover goods, beginning at £3.77 per month, which covers up to £1,500 worth of stuff.

With a company like Access, insurance is compulsory and also costs extra.

The rise of social storage

Running out of space to store stuff? Maybe a neighbour could take the slack

Costockage, external: Founded in 2012, this French company is building a "costockeurs" community who can "monetise their unused space"

Storemates, external: A UK company that came to prominence on the Dragon's Den TV show in 2012. They sign up people with spare space and connect them to people who need it

Roost, external: Founded in 2013 and operating in San Francisco, it facilitates peer-to-peer storage solutions, including car parking spaces as well as attics and lofts

Spacer, external: Founded in 2015, describes itself as "Australia's marketplace for space", releasing money from "idle assets"

While start-ups increasingly target the competitive social storage space, a new company is trying to make money out of our shorter-term storage needs - the few hours we have to kill before taking a train, for example.

Stasher, external, set up by a group of Oxford University economics graduates, is building a constellation of small shops and kiosks that will look after your luggage for short periods of time.

They have 30 signed up so far in England, near bus and train stations, which you can find on the Stasher app.

Stasher is aiming to undercut the left luggage market

In November, they booked in more than 700 pieces of luggage. With private investment just signed, the trio want to expand and take on the "left luggage" industry.

But hang on - is this safe?

I take my rucksack to a newsagent near London's Euston station to put Stasher to the test. It's a far cry from the normal left luggage point at the station, which has uniformed guards scanning bags.

Shop supervisor Modo seems busy serving customers. But he tells me my bag will be fine in the store room. He signed up because he has space and can easily generate extra cash from his prime spot.

I'm used to picking up Amazon packages from newsagents, thanks to their Pass My Parcel service, but this feels more risky.

Would you store valuables at a newsagent?

What if I'm a tourist who has gone boating in Hyde Park and had such a great time that I get back after the store has shut? And my passport is in there?

"We don't recommend storing essentials," says Stasher co-founder Anthony Collias.

"We could send on the items," he adds, "and pay for it, depending on who's at fault."

If items are damaged you are covered for up to £100 - not enough to cover a good camera or smartphone, of course.

But in Euston, which has a 24-hour service, it would have cost £12.50 to leave my bag for 24 hours. At the newsagent it was £5.

Will that be enough of a saving to persuade people to use the service? A straw poll of people waiting at Euston station revealed that most were interested in the idea.

For some small shops struggling on the High Street, it might feel like a lifeline.

Follow Dougal Shaw, external on Twitter.

Click here for more Technology of Business features and follow series editor Matthew Wall, external on Twitter.