How fertiliser helped feed the world

- Published

It has been called one of the greatest inventions of the 20th Century, and without it almost half the world's population would not be alive today.

A hundred years ago two German chemists, Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch, devised a way to transform nitrogen in the air into fertiliser, using what became known as the Haber-Bosch process.

But Haber's place in history is controversial.

He is also considered the "father of chemical warfare" for his years of work developing and weaponising chlorine and other poisonous gases during World War One.

Fritz Haber's work weaponising poisonous gases during World War One was extremely controversial

Plants need nitrogen: it is one of their five basic requirements, along with potassium, phosphorus, water and sunlight.

In a natural state, plants grow, they die, the nitrogen they contain returns to the soil, and new plants use it to grow.

Agriculture disrupts that cycle: we harvest the plants, and eat them.

From the earliest days of agriculture, farmers discovered various ways to prevent crop yields from declining over time: by restoring nitrogen to their fields.

Manure has nitrogen. So does compost.

The roots of legumes host bacteria that replenish nitrogen levels.

That is why it helps to include peas or beans in crop rotation.

Industrial process

But these techniques struggle to fully satisfy a plant's appetite for nitrogen.

Add more, and the plant grows better.

That is exactly what Fritz Haber worked out how to do, driven in part by the promise of a lucrative contract from the chemical company BASF.

That company's engineer, Carl Bosch, then managed to replicate Haber's process on an industrial scale.

Both men later won Nobel Prizes - controversially, in Haber's case, as many by then considered him a war criminal.

Find out more

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations which have helped create the economic world we live in.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service.

You can listen online and find information about the programme's sources or subscribe to the programme podcast.

The Haber-Bosch process is perhaps the most significant example of what economists call "technological substitution", where we seem to have reached some basic physical limit, then find a workaround.

For most of human history, if you wanted more food to support more people, then you needed more land.

But the thing about land, as Mark Twain once joked, is that they are not making it any more.

Haber and Bosch provided a substitute: instead of more land, make nitrogen fertiliser.

It was like alchemy.

"Brot aus Luft", as Germans put it, or "Bread from air".

From air and quite a lot of fossil fuels.

How it is done

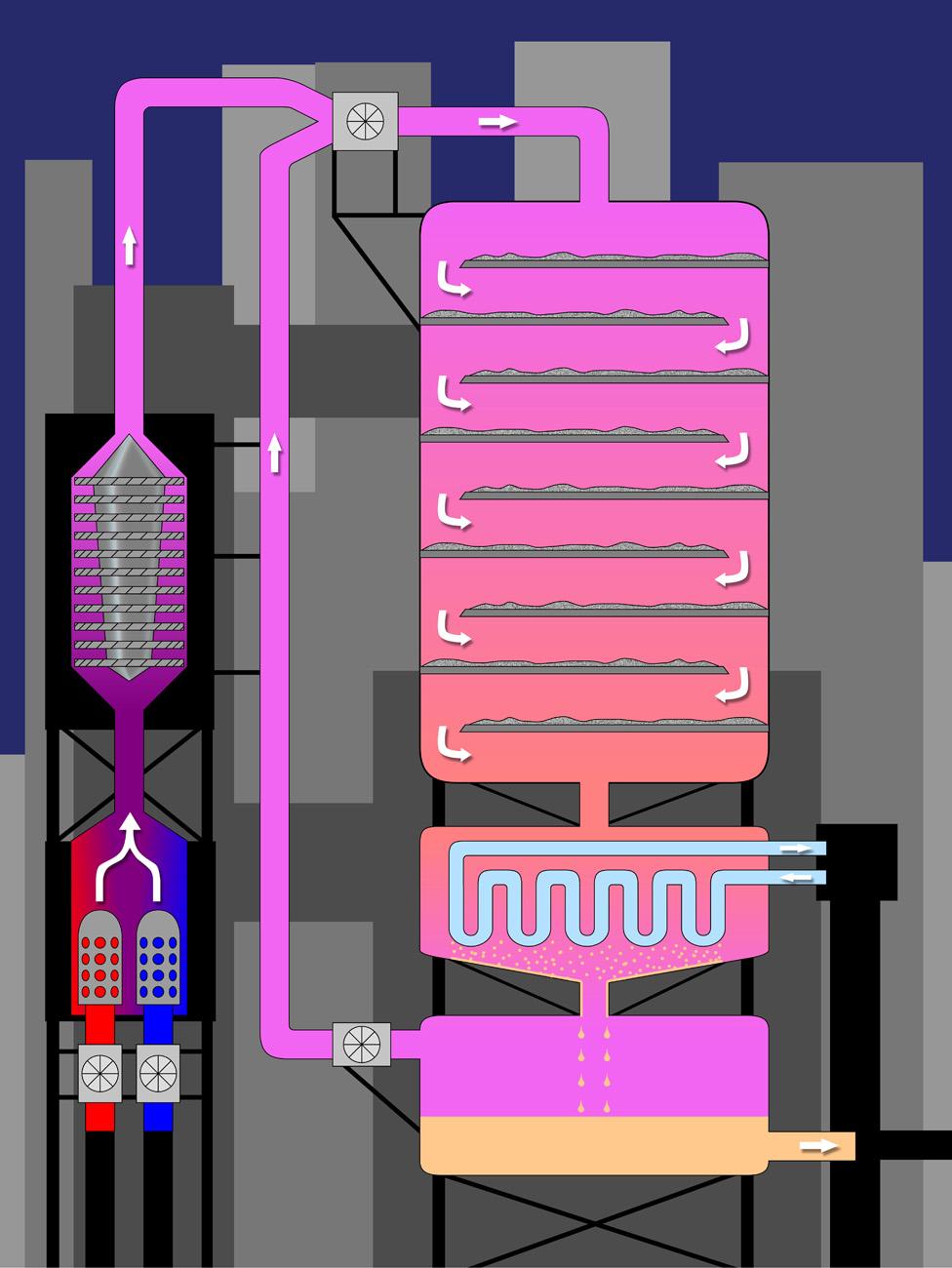

First of all, you need natural gas as a source of hydrogen, the element to which nitrogen binds to form ammonia.

Then you need energy to generate extreme heat and pressure.

Schematic diagram of the Haber-Bosch process to make ammonia from nitrogen

Haber discovered that was necessary, with a catalyst, to break the bonds between air's nitrogen atoms and persuade them to bond with hydrogen instead.

Imagine the heat of a wood-fired pizza oven, with the pressure you would experience 2km under the sea.

To create those conditions on a scale sufficient to produce 160 million tonnes of ammonia a year - the majority of which is used for fertiliser - the Haber-Bosch process today consumes more than 1% of all the world's energy.

That is a lot of carbon emissions.

Environmental damage

And there is another very serious ecological concern.

Only some of the nitrogen in fertiliser makes its way via crops into human stomachs, perhaps as little as 15%.

Most of it ends up in the air or water.

This is a problem for several reasons.

Compounds like nitrous oxide are powerful greenhouse gases.

They pollute drinking water.

They also create acid rain, which makes soils more acidic, disrupting ecosystems, and threatening biodiversity.

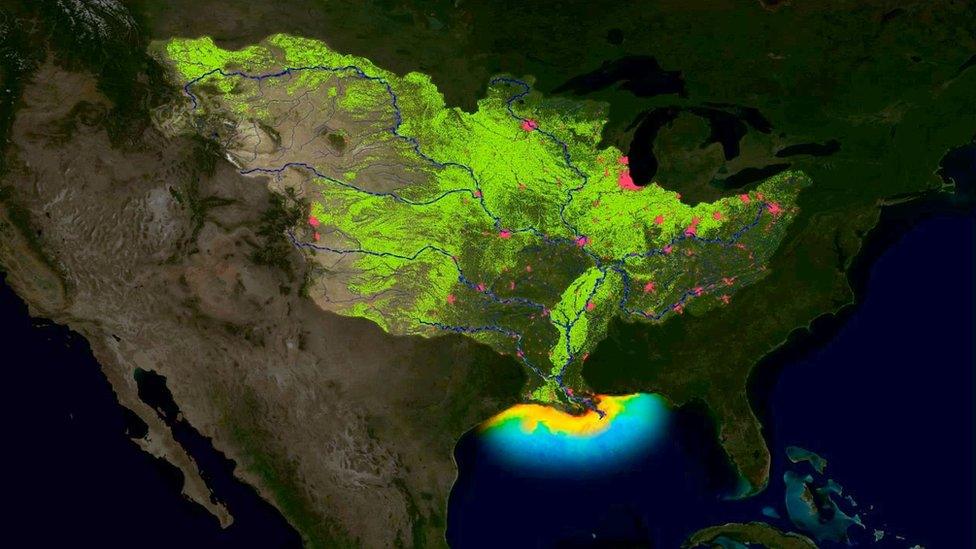

Phosphorus and other nutrients can create marine dead zones such as this one in the Gulf of Mexico

When nitrogen compounds run off into rivers, they likewise promote the growth of some organisms more than others.

The results include ocean "dead zones", where blooms of algae near the surface block out sunlight and kill the fish below.

The Haber-Bosch process is not the only cause of these problems, but it is a major one, and it is not going away.

Demand for fertiliser is projected to double in the coming century.

In truth, scientists still do not fully understand the long-term impact on the environment of converting so much stable, inert nitrogen from the air into various other, highly reactive chemical compounds.

Population growth

We are in the middle of a global experiment.

One result is already clear: plenty of food for lots more people.

If you look at a graph of global population, you will see it shoot upwards just as Haber-Bosch fertilisers start being widely applied.

Again, Haber-Bosch was not the only reason for the spike in food yields.

New varieties of crops like wheat and rice also played their part.

Still, if we farmed with the best techniques available in Fritz Haber's time, the earth would support about four billion people.

Our current population is around seven and a half billion, and growing.

New strains of rice such as the IR8 variety first planted in 1967 also boosted the global food supply

Back in 1909, as Haber triumphantly demonstrated his ammonia process, he could hardly have imagined how transformative his work would be.

On one side of the ledger, food to feed billions more human souls; on the other, a sustainability crisis that will need more genius to solve.

For Haber himself, the consequences of his work were not what he expected.

As a young man, he converted from Judaism to Christianity, aching to be accepted as a German patriot.

Beyond his work on weaponising chlorine, the Haber-Bosch process also helped Germany in World War One.

Ammonia can make explosives, as well as fertiliser.

Not just bread from air, but bombs too.

When the Nazis took power in the 1930s, however, none of this outweighed his Jewish roots.

Stripped of his job and kicked out of the country, Haber died, in a Swiss hotel, a broken man.

Tim Harford is the FT's Undercover Economist. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy was broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can listen online and find information about the programme's sources or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published25 November 2016

- Published26 October 2016

- Published17 February 2016

- Published3 June 2015