The simple steel box that transformed global trade

- Published

Perhaps the defining feature of the global economy is precisely that it is global.

Toys from China, copper from Chile, T-shirts from Bangladesh, wine from New Zealand, coffee from Ethiopia, and tomatoes from Spain.

Like it or not, globalisation is a fundamental feature of the modern economy.

In the early 1960s, world trade in merchandise was less than 20% of world economic output, or gross domestic product (GDP).

Now, it is around 50% but not everyone is happy about it.

There is probably no other issue where the anxieties of ordinary people are so in conflict with the near-unanimous approval of economists.

Arguments over trade tend to frame globalisation as a policy - maybe even an ideology - fuelled by acronymic trade deals like TRIPS and TTIP.

But perhaps the biggest enabler of globalisation has not been a free trade agreement, but a simple invention: the shipping container.

It is just a corrugated steel box, 8ft (2.4m) wide, 8ft 6in (2.6m) high, and 40ft (12m) long but its impact has been huge.

Find out more

BBC World Service's 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy programme highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the global economy.

You can find more information about its sources and listen online or download the programme podcast.

Consider how a typical trade journey looked before its invention.

In 1954, an unremarkable cargo ship, the SS Warrior, carried merchandise from New York to Bremerhaven in Germany.

It held just over 5,000 tonnes of cargo - including food, household goods, letters and vehicles - which were carried as 194,582 separate items in 1,156 different shipments.

Just keeping track of the consignments as they moved around the dockside warehouses was a nightmare.

But the real challenge was physically loading such ships.

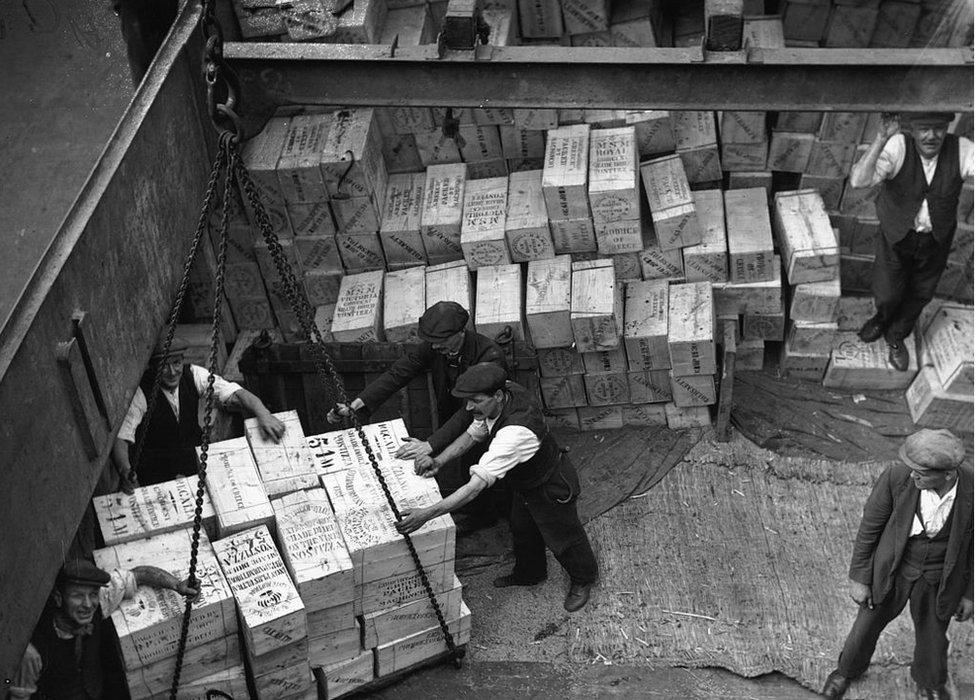

Loading by hand

Longshoremen would pile the cargo onto a wooden pallet on the dock.

The pallet would be hoisted in a sling and deposited in the hold.

More longshoremen carted each item into a snug corner of the ship, poking the merchandise with steel hooks until it settled into place against the curves and bulkheads of the hold, skilfully packed so that it would not shift on the high seas.

There were cranes and forklifts but much of the merchandise, from bags of sugar heavier than a man to metal bars the weight of a small car, was shifted with muscle power.

This was dangerous work.

In a large port, someone would be killed every few weeks.

In 1950, New York averaged half a dozen serious incidents every day, and its port was safer than many.

Researchers studying the SS Warrior's trip to Bremerhaven concluded the ship had taken ten days to load and unload, as much time as it had spent crossing the Atlantic.

In today's money, the cargo cost around $420 (£335) a tonne to move.

Given typical delays in sorting and distributing the cargo by land, the whole journey might take three months.

Sixty years ago, then, shipping goods internationally was costly, chancy, and immensely time-consuming.

Surely there had to be a better way?

Vested interests

Indeed there was: put all the cargo into big standard boxes, and move those.

But inventing the box was the easy bit - the shipping container had already been tried in various forms for decades.

The real challenge was overcoming the social obstacles.

To begin with, the trucking companies, shipping companies, and ports could not agree on a standard size.

Some wanted large containers while others wanted smaller versions; perhaps because they specialised in heavy goods or trucked on narrow mountain roads.

Then there were the powerful dockworkers' unions, who resisted the idea.

Yes the containers would make the job of loading ships safer but it would also mean fewer jobs.

Malcom McLean understood how revolutionary containerisation could be for shipping

US regulators also preferred the status quo.

The sector was tightly bound with red tape, with separate sets of regulations determining how much that shipping and trucking companies could charge.

Why not simply let companies charge whatever the market would bear - or even allow shipping and trucking companies to merge, and put together an integrated service?

Perhaps the bureaucrats too were simply keen to preserve their jobs.

Such bold ideas would have left them with less to do.

Spotting an opportunity

The man who navigated this maze of hazards, and who can fairly be described as the inventor of the modern shipping container system, was called Malcom McLean.

McLean did not know anything about shipping but he was a trucking entrepreneur.

He knew plenty about trucks, plenty about playing the system, and all there was to know about saving money.

As Marc Levinson explains in his book, The Box, McLean not only saw the potential of a shipping container that would fit neatly onto a flat bed truck, he also had the skills and the risk-taking attitude needed to make it happen.

First, McLean cheekily exploited a legal loophole to gain control of both a shipping company and a trucking company.

Then, when dockers went on strike, he used the idle time to refit old ships to new container specifications.

He repeatedly plunged into debt.

He took on "fat cat" incumbents in Puerto Rico, revitalising the island's economy by slashing shipping rates to the United States.

He cannily encouraged New York's Port Authority to make the New Jersey side of the harbour a centre for container shipping.

But probably the most striking coup took place in the late 1960s, when Malcom McLean sold the idea of container shipping to perhaps the world's most powerful customer: the US Military.

Impetus of war

Faced with an unholy logistical nightmare in trying to ship equipment to Vietnam, the military turned to McLean's container ships.

Containers work much better when they are part of an integrated logistical system, and the US military was perfectly placed to implement that.

Even better, McLean realised that on the way back from Vietnam, his empty container ships could collect payloads from the world's fastest growing economy, Japan.

And so trans-Pacific trading began in earnest.

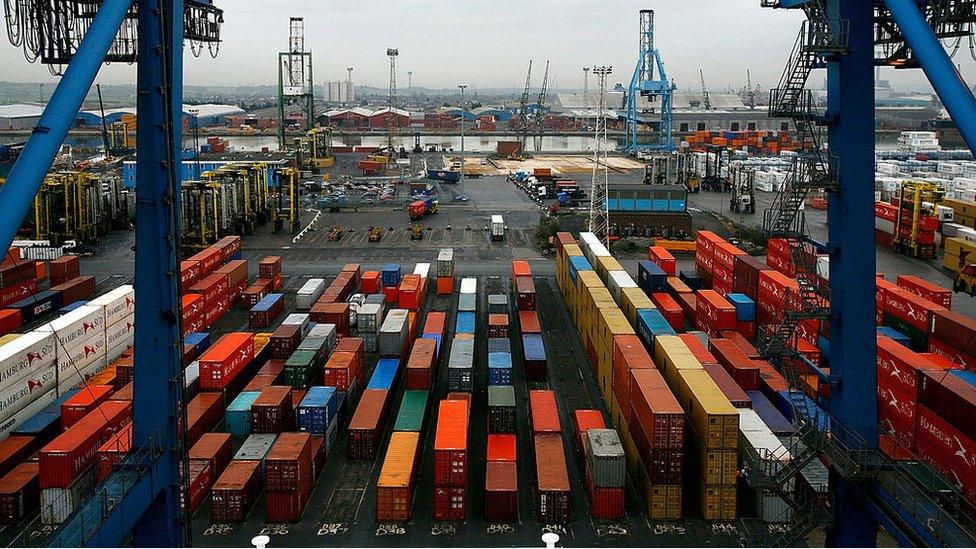

A modern shipping port would be unrecognisable to a hardworking longshoreman of the 1950s.

Even a modest container ship might carry 20 times as much cargo as the SS Warrior did, yet disgorge its cargo in hours rather than days.

Gigantic cranes weighing 1,000 tonnes apiece lock onto containers which themselves weigh upwards of 30 tonnes, and swing them up and over on to a waiting transporter.

The colossal ballet of engineering is choreographed by computers, which track every container as it moves through a global logistical system.

The refrigerated containers are put in a hull section with power and temperature monitors.

The heavier containers are placed at the bottom to keep the ship's centre of gravity low.

The entire process is scheduled to keep the ship balanced.

And after the crane has released one container onto a waiting transporter, it will grasp another before swinging back over the ship, which is being simultaneously emptied and refilled.

Zero-cost transport?

Not everywhere enjoys the benefits of the containerisation revolution.

Many ports in poorer countries still look like New York in the 1950s.

Sub-Saharan Africa, in particular, remains largely cut off from the world economy because of poor infrastructure.

But for an ever-growing number of destinations, goods can now be shipped reliably, swiftly and cheaply.

Rather than the $420 (£335) that a customer would have paid to get the SS Warrior to ship a tonne of goods across the Atlantic in 1954, you might now pay less than $50 (£39).

Indeed, economists who study international trade often assume that transport costs are zero.

It keeps the mathematics simpler, they say, and thanks to the shipping container, it is nearly true.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. The 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy programme was broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about its sources and listen online or download the programme podcast.

- Published4 November 2016

- Published31 October 2016

- Published1 September 2016

- Published26 July 2016