Smart machines v hackers: How cyber warfare is escalating

- Published

Smart machines are helping businesses defend themselves against hackers

There is a gaping hole in the digital defences that companies use to keep out cyber thieves.

The hole is the global shortage of skilled staff that keeps security hardware running, analyses threats and kicks out intruders.

Currently, the global security industry is lacking about one million trained workers, suggests research by ISC2 - the industry body for security professionals. The deficit looks set to grow to 1.8 million within five years, it believes.

The shortfall is widely recognised and gives rise to other problems, says Ian Glover, head of Crest - the UK body that certifies the skills of ethical hackers.

"The scarcity is driving an increase in costs," he says. "Undoubtedly there's an impact because businesses are trying to buy a scarce resource.

"And it might mean companies are not getting the right people because they are desperate to find somebody to fill a role."

While many nations have taken steps to attract people in to the security industry, Mr Glover warns that those efforts will not be enough to close the gap.

Help has to come from another source: machines.

"If you look at the increase in automation of attack tools then you need to have an increase in automation in the tools we use to defend ourselves," he says.

'Drowning' in data

That move towards more automation is already under way, says Peter Woollacott, founder and chief executive of Sydney-based Huntsman Security, adding that the change was long overdue.

For too long, security has been a "hand-rolled" exercise, he says.

That is a problem when the analysts expected to defend companies are "drowning" in data generated by firewalls, PCs, intrusion detection systems and all the other appliances they have bought and installed, he says.

Automation is nothing new, says Oliver Tavakoli, chief technology officer at security firm Vectra Networks - early uses helped antivirus software spot novel malicious programmes.

Humans can't always spot unusual activity on a complex network

But now machine learning is helping it go much further.

"Machine learning is more understandable and more simplistic than AI [artificial intelligence]," says Mr Tavakoli, but that doesn't mean it can only handle simple problems.

The analytical power of machine learning derives from the development of algorithms that can take in huge amounts of data and pick out anomalies or significant trends. Increased computing power has also made this possible.

These "deep learning" algorithms come in many different flavours.

Some, such as OpenAI, are available to anyone, but most are owned by the companies that developed them. So larger security firms have been snapping up smaller, smarter start-ups in an effort to bolster their defences quickly.

'Not that clever'

Simon McCalla, chief technology officer at Nominet, the domain name registry that oversees the .uk web domain, says machine learning has proven its usefulness in a tool it has created called Turing.

This digs out evidence of web attacks from the massive amounts of queries the company handles every day - queries seeking information about the location of UK websites.

Mr McCalla says Turing helped analyse what happened during the cyber-attack on Lloyds Bank in January that left thousands of customers unable to access the bank's services.

The DDoS [distributed denial of service] attack generated a huge amount of data to handle for that one event, he says.

Spammers can be stopped by letting machine learning analyse data traffic

"Typically, we handle about 50,000 queries every second. With Lloyds it was more than 10 times as much."

Once the dust had cleared and the attack was over, Nominet had handled a day's worth of traffic in a couple of hours.

Turing absorbed all the information made to Nominet's servers and used what it learned to give early warnings of abuse and intelligence on people gearing up for a more sustained attack.

It logs the IP [internet protocol] addresses of hijacked machines sending out queries to check if an email address is "live".

"Most of what we see is not that clever, really," he says, but adds that without machine learning it would be impossible for human analysts to spot what was going on until its intended target, such as a bank's website, "went dark".

The analysis that Turing does for Nominet is now helping the UK government police its internal network. This helps to block staff accessing dodgy domains and falling victim to malware.

Mayhem and order

There are also even more ambitious efforts to harness the analytical ability of machine learning.

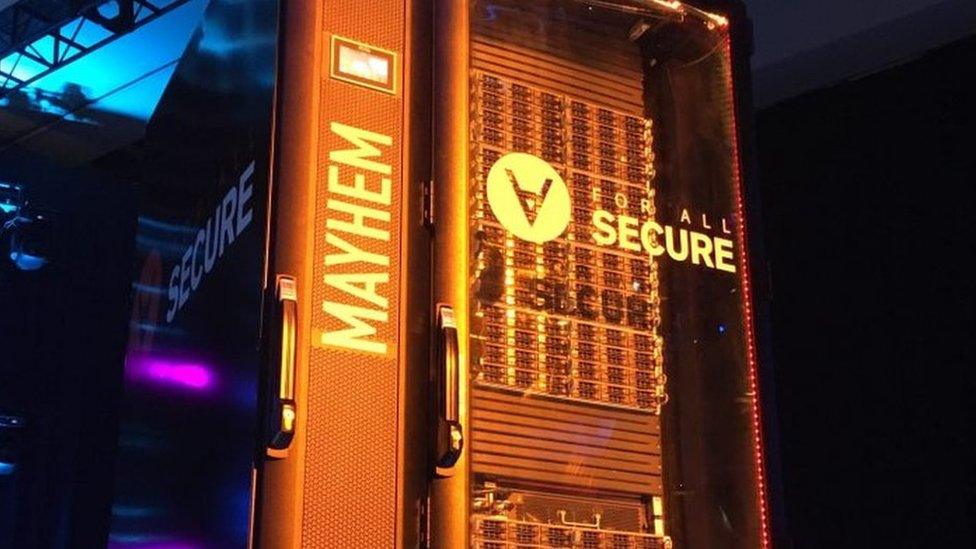

At the Def Con hacker gathering last year, Darpa, the US military research agency, ran a competition that let seven smart computer programs attack each other to see which was the best at defending itself.

The winner, called Mayhem, is now being adapted so that it can spot and fix flaws in code that could be exploited by malicious hackers.

The Mayhem computer won a challenge to find a smart computer that can spot bugs

Machine learning can correlate data from lots of different sources to give analysts a rounded view of whether a series of events constitutes a threat or not, says Mr Tavakoli.

It can get to know the usual ebbs and flows of data in an organisation and what staff typically get up to at different times of the day.

So when cyber thieves do things such as probing network connections or trying to get at databases, that anomalous behaviour raises a red flag.

But thieves have become very good at covering their tracks and, on a big network, those "indicators of compromise" can be very difficult for a human to pick out.

So now cybersecurity analysts can sit back and let the machine-learning systems crunch all the data and pick out evidence of serious attacks that really deserve human attention.

"It's like the surgeons who just do the cutting," says Mr Tavakoli. "They do not prep the patient, they are just there to operate and they do it very well."

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external

Click here for more Technology of Business features, external