Could a national maximum wage work?

- Published

- comments

Jeremy Corbyn has called for a high earnings cap

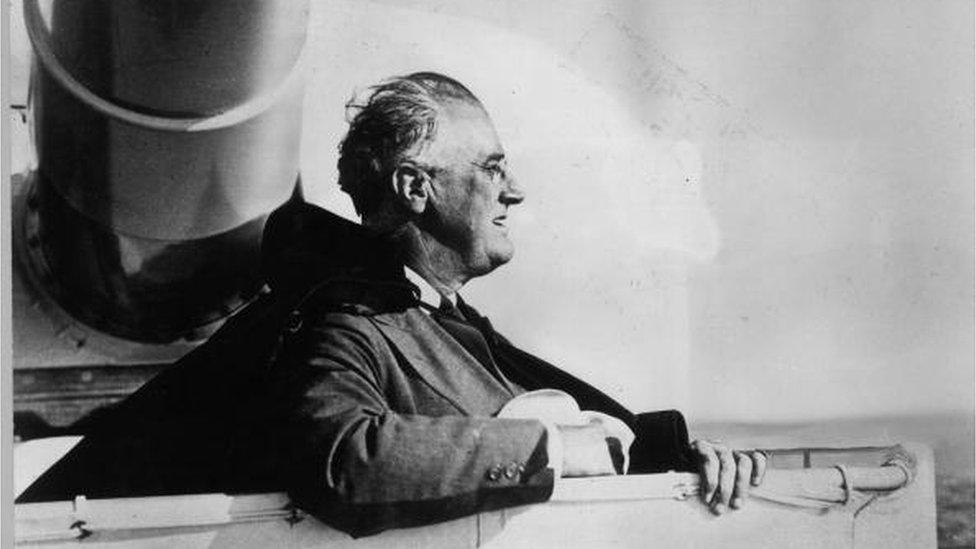

In 1942, Franklin D Roosevelt - not known as a Socialist radical, though he had his moments - proposed that anyone earning over $25,000 should be taxed at 100%.

Effectively, the President of the United States was calling for a high pay cap of, in today's money, just under $400,000 or £330,000.

Interviewed this morning on the Today programme, Jeremy Corbyn rekindled the debate on high pay, saying that a "cap" should be considered for the highest earners.

With legislation if necessary.

Franklin D Roosevelt - not known as a socialist radical

Given that a direct limit (making it "illegal" for example for anyone to earn over, say, £200,000) would be almost impossible to enforce in a global economy where income takes many forms - salary, investments, returns on assets - very high marginal rates of tax could be one way to control very high levels of pay.

Another could be by imposing limits on the pay ratio between higher and lower earners in a company - possibly a more politically palatable option.

The High Pay Centre, for example, supports considering this approach.

Their research reveals the ratio has increased substantially.

"The average pay of a FTSE 100 chief executive has rocketed from around £1m a year in the late 1990s - about 60 times the average UK worker - to closer to £5m today, more than 170 times," the organisation said in 2014.

Firms have been under fire over high rates of executive pay

In its submission to the review of corporate governance by the House of Commons business select committee in October, the centre said executive pay was "out of control".

It is only relatively recently that high marginal rates of tax have been dropped as a way of limiting "out of control" pay.

Although America's Congress couldn't quite stomach the wartime 100% super tax (the actor Ann Sheridan commented "I regret that I have only one salary to give to my country") by 1945 the marginal rate on incomes over $200,000 was 94%.

Post-war, very high rates of income tax on high earners were the norm and income inequality was far lower.

By the 1970s in the UK, the marginal rate on higher incomes was 84%, a figure that rose to 98% with the introduction of a surcharge on investment income.

Denis Healey, then the Labour chancellor, famously said he wanted to "squeeze the rich until the pips squeak" - a quote he subsequently denied.

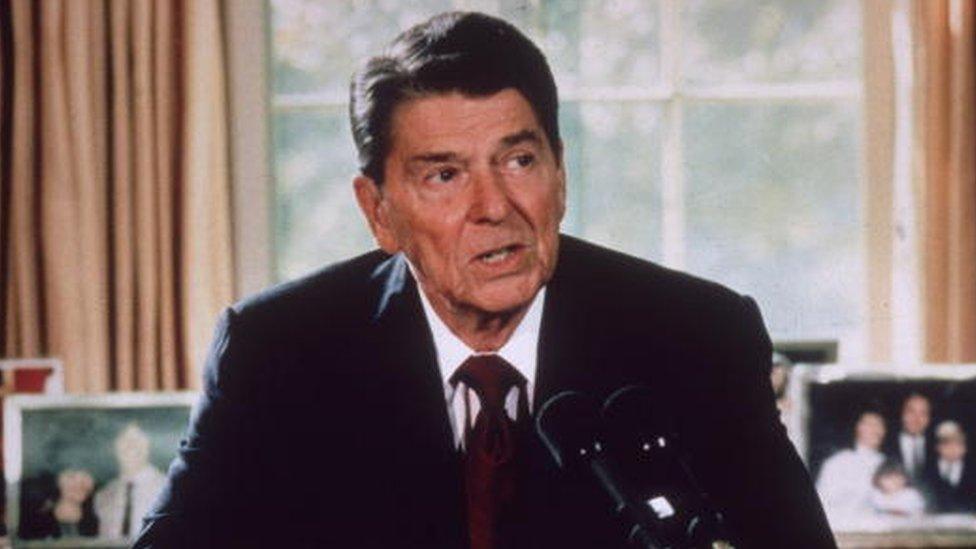

The mood changed with economic stagnation, industrial strife and the arrival of mainstream monetarism and its political leaders - Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

Strikers gather round a brazier at a picket line in London in 1979

They built an economic and political philosophy based on a belief that it wasn't the state's job to spend, in Thatcher's famous phrase, "other people's money" - it was better to allow people to retain the money they earned and spend it as they saw fit, even if it was an awful lot.

Lower levels of income tax were the result and economic growth strengthened for a period.

Income inequality also grew, maybe a price worth paying for the economic riches which, it was argued, were flowing around the country.

For many, especially since the financial crisis, the pendulum has swung back, away from lower taxes towards a more punitive approach to high incomes.

Mr Corbyn was speaking about a belief that some individuals at the top of the income scale now have far too much money to spend compared with the "just about managing" classes.

Theresa May has also made it clear that "fat cat pay" is on her radar.

The economics of high pay and whether it should be limited are based on a judgement between two competing interests.

Tax or not?

The first is summed up by the Laffer Curve, popularised by the US economist Arthur Laffer, which argues that if income taxes are too high (or pay limits in any guise too strong) they reduce the incentive to work, which ultimately affects growth, national wealth and government income.

At its most basic, under the "Laffer rules" a 0% income tax rate would collect no revenue.

And a 100% income tax rate would also collect no revenue, as no one would bother working.

Ronald Reagan slashed the top rates of US income tax

It has been used from Reagan onwards as the economic underpinning for an argument that lower taxes support growth.

In the 1980s, US government revenues increased as taxes were cut, although that was as much to do with general strong levels of growth as it was to do with the tax cuts themselves.

The second, contrary, economic pressure, as countless studies from the World Bank and others have shown, is that countries with high levels of income inequality have lower levels of growth.

Tackling that inequality, by whatever method, incentivises people to work more effectively.

The problem is that lifting lower wages by increasing, for example, productivity levels, could be a more effective way of reducing the gap between low and high pay, although it would take many years of concerted effort to be successful.

Since the 1970s, the notion of a government inspired "incomes policy" has been - in the popularity stakes - right up there with multi-millionaire bankers at a meeting of Momentum, the organisation that supports Mr Corbyn's Labour leadership.

But, ever since the introduction of the minimum wage in the 1990s, the government has made it clear that the amount people are paid is not simply a matter for private businesses and the free market.

Mr Corbyn has said he wants to consider a national maximum wage.

Many might nod in agreement.

How to do it, though, and whether it is economically helpful for growth, is a very different matter.