What went wrong at Sears?

- Published

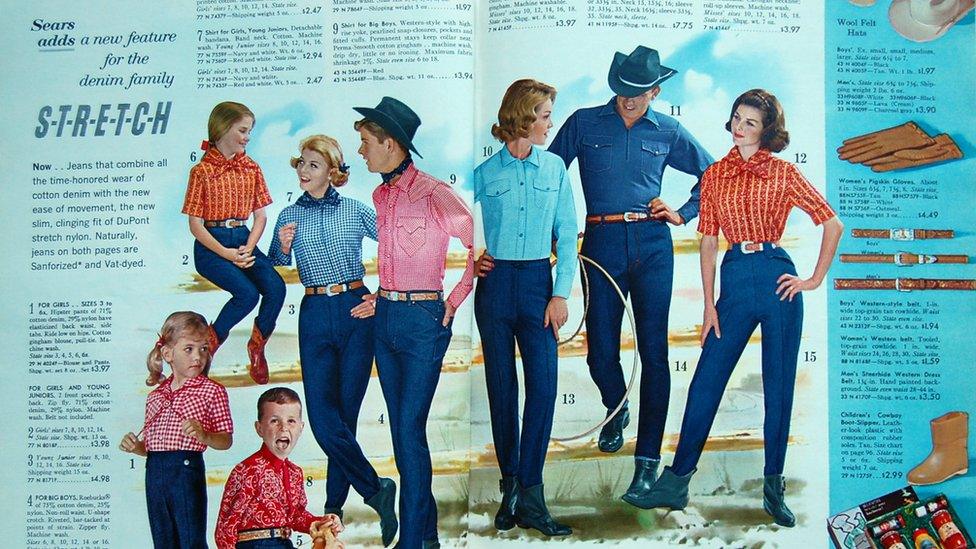

Pages from Sears' 1962 Christmas catalogue

To say that Sears is a household name in US retail is an understatement.

The 130-year-old company operates one of America's best-known department store brands, Sears, Roebuck & Company, along with the ubiquitous Kmart chain, and was America's largest retail company until 1989.

But the firm has recently found itself in a crisis as it struggles to turn a profit as Americans increasingly shop online rather than in shopping centres.

In January, the company behind the group said it was selling off a major subsidiary and shutting more than 100 stores in an attempt to bolster its finances.

Some analysts believe that, short of a miracle, Sears Holdings will go under within the next few years.

So how did things go so wrong, and can the business do anything to turn itself around?

Sears is one America's best-known department store brands

Sears began life as a catalogue company in 1886 and over the next century grew to become a retail behemoth, selling everything from appliances and clothes to car repairs.

But its sales have fallen from $53bn in 2006, external to just $25.1bn in 2015 and it is losing more than $1bn a year, external.

Neil Saunders, chief executive of Conlumino, a retail research agency in New York, says the firm's "biggest problem" is that the US retail landscape has changed dramatically.

"One of the fundamentals is that people shop more online and less in malls, which is where Sears' stores are usually located," he tells the BBC.

Sears fast facts

Sears was founded by Richard Warren Sears and Alvah Curtis Roebuck in 1886 as a mail order catalogue company, and opened its first retail locations in 1925.

In terms of revenue it was America's largest retailer until 1989, when Walmart overtook it, external. It remains one of America's largest department store groups.

The company operates through its subsidiaries, including Sears, Roebuck and Co. and Kmart, and owns a range of other brands, external.

Its revenues were $25.1bn in 2015, external compared to $31.2bn in 2014.

"The second problem is that Sears hasn't invested in its retail outlets for a long time - that includes its staff, new products and innovation."

This has come at a time of unprecedented competition from online shopping giants such as Amazon.

Women's clothing on sale in a 1935 Sears catalogue

But while peers like JC Penney and Macy's have tried to stay fresh, Sears has not kept up, says Mr Saunders.

"Shoppers have changed drastically in the past several years and now demand so much more from retailers across the board, from both a digital and physical perspective," adds Tiffany Hogan, an expert on US retail at Kantar Retail.

"Sears has great name recognition in the US and was strong for so long, but has not capitalised on that name to the fullest to keep the chain relevant."

'Long-term transformation'

Sears Holdings' chief executive, Eddie Lampert, says the firm is in the midst of a "long-term transformation" to succeed both online and through its stores.

He is also banking on the company's rewards programme, Shop Your Way, where frequent buyers accumulate points for their Sears and Kmart purchases and turn them into coupons and discounts.

Some say Sears has not invested enough in its stores

However, none of this has made the firm profitable and it is heavily in debt.

In response, Sears has put forward a turnaround plan, external involving selling off its Craftsman tool brand for around $900m, closing 150 stores, and borrowing hundreds of millions from Mr Lampert's hedge fund ESL, which is also Sears' biggest investor.

Shares in the firm picked up on the news but have since eased back; analysts do not seem convinced, either.

Moody's Christina Boni says the company had been supporting itself by selling off assets, "but obviously that can't last forever".

Matt McGinley from the investment bank Evercore ISI told Bloomberg earlier in January: "I don't think there is any viable path to any sort of profitability."

Sears Holdings will not comment on "rumour and speculation" about its future, but tells the BBC: "We believe that we have the resources to fund our transformation and meet all of our financial obligations."

Wider impacts

If, as some expect, the firm does go under it could have wider repercussions.

Sears Holdings' chief executive, Eddie Lampert, says he is investing in the firm's "long-term transformation"

"Even with just the 150 stores Sears has confirmed it will close, the local impacts [in the US] could be significant as Sears will leave a large footprint that US malls have to fill with alternative businesses," Ms Hogan says.

Yet Sears is not alone in its struggles, she says: "Across the landscape we're seeing retailers struggle with 'keeping up with the Jones's'... Women's clothing store chain the Limited just closed its doors, and a handful of other mall-based retailers are likely to follow in the next couple of years."

Ms Boni says that closures might be no bad thing, though.

"The US is currently 'over-stored', so we are beginning to see a flush out with store closures across many competitors.

"To that end it's a natural part of the cycle, and the long-term effect of stores shuttering isn't necessarily a bad thing."