Would you risk jail for a cup of tea?

- Published

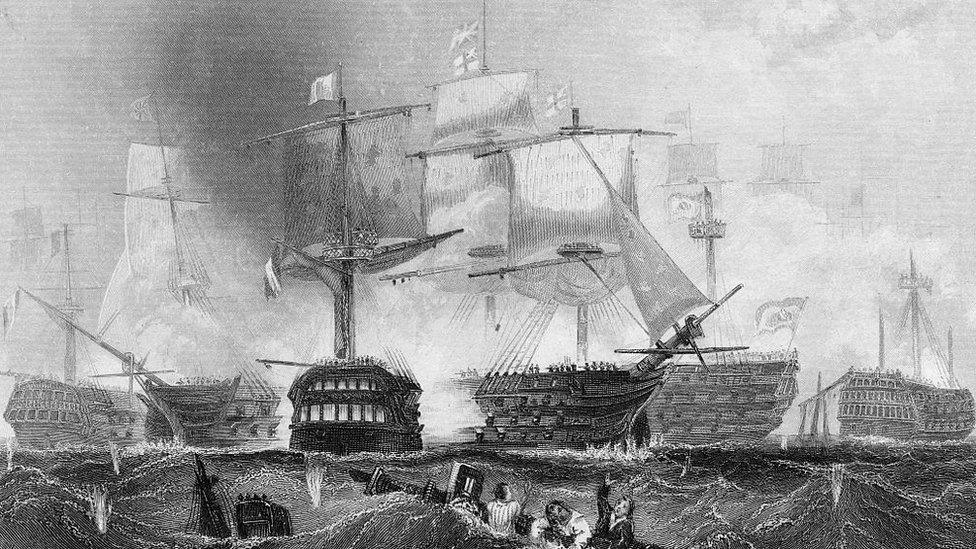

Smugglers being chased by the Royal Navy. Virtually every seaside community in Britain saw its share of smuggling in the 18th Century

A boat beaches in a lonely cove at night, the crew hurriedly unloading its cargo of tea to waiting men and pack horses while armed lookouts stand guard against a surprise swoop by the revenue men.

It may be a stereotypical image, but in the 18th Century, a cuppa was in such high demand that many Britons were willing to risk jail for the privilege.

In fact, this kind of smuggling was a vital part of Britain's economy for some 200 years.

It was a trade triggered by increasingly high tariffs or duties, taxes a merchant would have to pay to legally import tea.

The duties on importing tea reached a staggering 119% in the 1750s - which meant that if you could avoid paying the tax, the cost of your brew dropped by more than half.

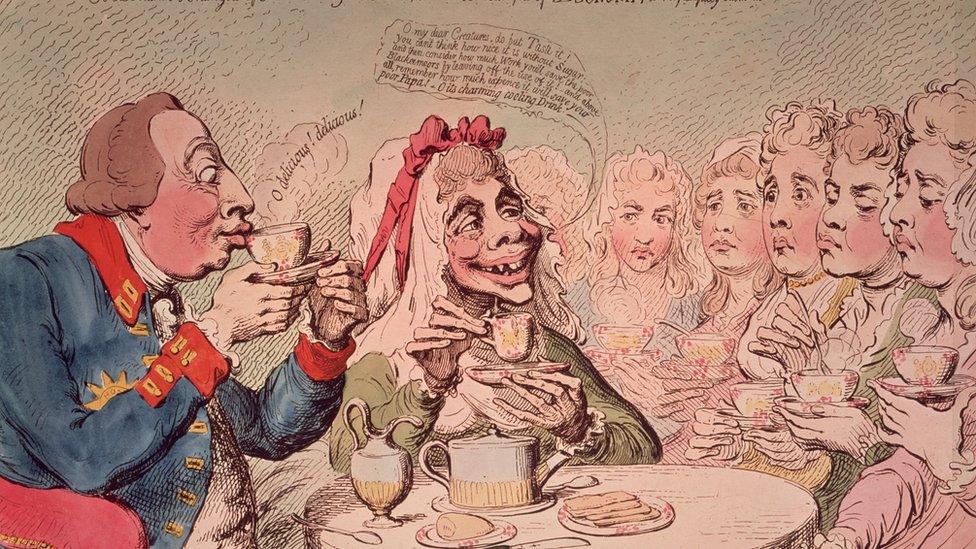

Tea became hugely popular in Britain in the 1700s

Not surprisingly many customers turned to the smugglers, who were willing to risk imprisonment or have their ships destroyed and goods seized if they were caught.

Free trade and smuggling are closely linked.

When import taxes or tariffs are low, there's not much profit to be made from smuggling.

Conversely, when a government makes it expensive to legally import items it encourages smugglers who can undercut the official price.

Tea taxes

Tea was one of the most important items illegally brought into Britain in the 18th Century - everybody wanted to drink it, but most could not afford it at the official price.

Tea chests in London in the 1950s - the nation's love affair with the drink has endured

In an age before income tax, tea duties accounted for 10% of government revenues, which was enough to pay for the Royal Navy, but as tariffs on it reached 119% it gave smugglers their chance.

"If you had high tariffs and goods people wanted, it gave smugglers a business opportunity," says Exeter University historian Helen Doe.

More than 3,000 tonnes of tea was smuggled into Britain a year by the late 1700s, with just 2,000 tonnes imported legally.

In some areas whole communities were dependent on smuggling, from landowners who might finance the operation down to the fishermen who might be crewing the boats.

Smuggling operations

There were three main types of smuggling, says Robert Blyth, senior curator at the National Maritime Museum in London.

A romanticised view of the smuggling trade; in reality smugglers often used threats of violence against customs men

"There's small-scale smuggling, where you might row your boat out to meet a ship and take off some of its cargo to sell illegally, the ship's captain declaring the missing cargo as 'spoiled at sea' when it gets to port to officially unload the rest," he says.

"Then there are commercially organised groups bringing contraband into harbours across the UK in a sophisticated operation.

"Finally, you have simple theft and pilfering in major ports like London from ships that have already moored, but have not yet been checked by the revenue."

Swedish traders

It wasn't just the British who were developing a taste for tea. The popularity of the drink in Sweden meant the country also played an important role in 18th Century smuggling into Britain.

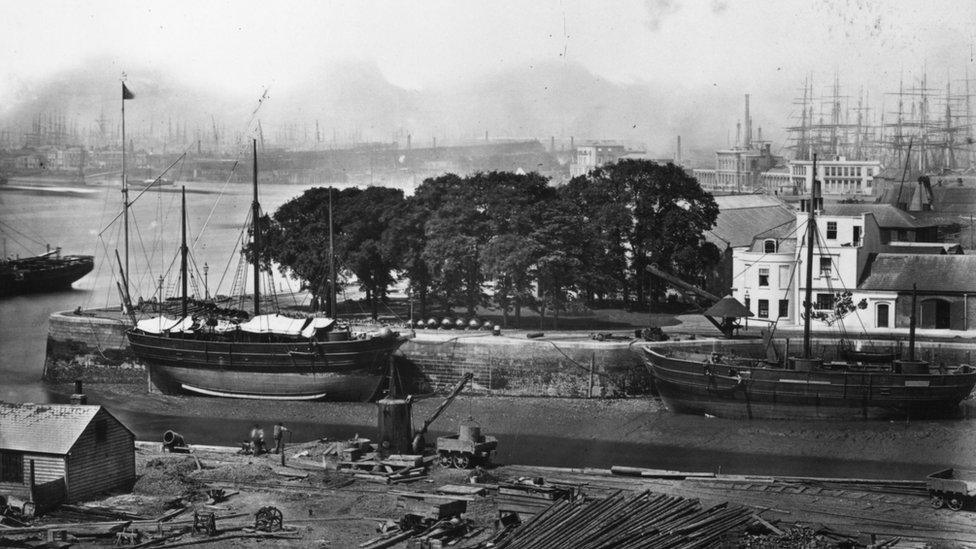

Gothenburg was the base for the Swedish East India Company's operations

Swedish East India Company merchants were able to buy the best quality Chinese tea because unlike other European countries they were prepared to pay in silver - rather than seeking to barter or trade.

Quite a few were actually Scottish, political refugees who had fled to Sweden after the failure of the 1745 Jacobite uprising, and who thus saw little wrong in avoiding paying tax to Britain's Hanoverian government.

So popular was this trade that newspapers in Scotland and northern England openly carried adverts for this smuggled tea, called "Gottenburgh Teas".

Building specialised docks with guarded warehouses helped cut down stealing of goods once ships had reached London

For many tea traders in Britain, buying smuggled tea made sense, says Derek Janes, a history researcher at Exeter University.

"Britain's own East India Company had a monopoly on tea imports, so if an Edinburgh merchant wanted to buy it you had to go to London, you had to pay to bring it back to Scotland - and you had to pay upfront.

"But if you bought it from the smugglers it would be half the price - with no tax to pay - they would deliver to your door and you would get up to four months credit. A much better service!"

One of those involved in this trade was John Nisbet, who became rich enough to commission architect John Adams to design his harbourside mansion in Eyemouth in the Scottish borders, complete with hidden partitions for the smuggled tea.

Often when the customs officials got a tip-off about his ship it was too late - the cargo had already been smuggled ashore. And if a smuggler did have his goods seized, he could sometimes negotiate a price to buy it back from the government.

"John Nisbet had a ship and cargo seized, but you can see the lawyer for the board of customs in Edinburgh say that the witnesses had disappeared, so the customs did a deal. He paid £250 to get it all back, which still left him in profit," says Mr Janes.

Increased policing

By 1784, the government realised high tariffs were creating more problems than they were worth and cut tea duties to just 12.5%, making tea affordable for most people. The change meant smugglers switched to bringing in spirits and wine instead.

The end of the Napoleonic wars saw the Royal Navy in undisputed command of the Channel, making it much harder for smugglers to avoid detection

The Napoleonic wars saw an upsurge in smuggling, but after 1815 with the Royal Navy in undisputed command of the sea, its days were numbered.

Ultimately, many smugglers failed. In the long run, the business did not generate enough cash to compensate for the risks of losing stock or ships to the customs. John Nisbet may have been able to afford a fine house but even he went bust eventually, the result of one too many cargo seizures.

In the end, it was economics that finally put an end to the smuggling era. Britain's adoption of a free trade policy in the 1840s reduced import duties significantly, making smuggling no longer viable.

And thanks to that shift in policy, you can now sit back, relax and enjoy a nice cup of tea without any fears of going to prison.

Follow Tim Bowler on Twitter @timbowlerbbc, external