Is robotics a solution to the growing needs of the elderly?

- Published

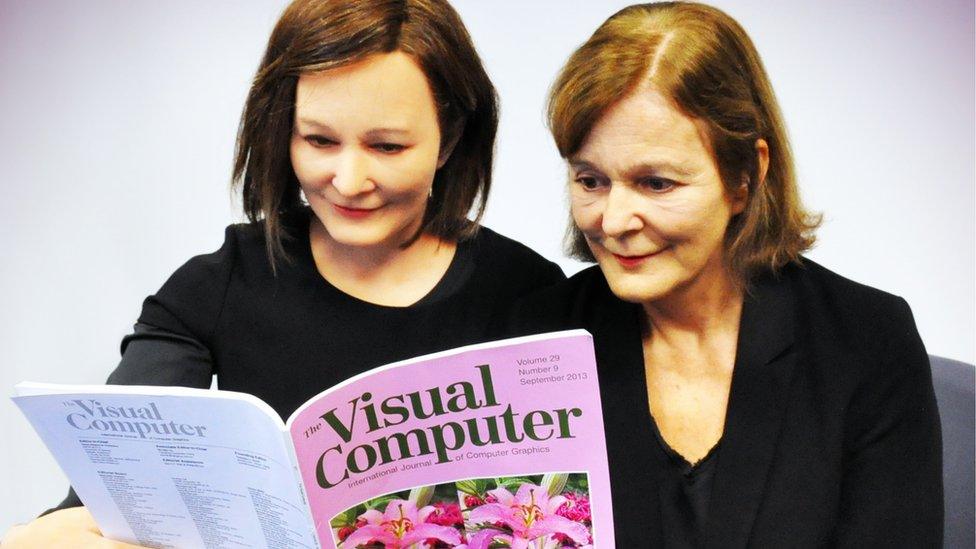

Nadine started life as a robotic receptionist but Professor Nadia Thalmann believes she can be developed into a carer

The receptionist at the Institute of Media Innovation, at Singapore's Nanyang Technological University, is a smiling brunette called Nadine.

From a distance, nothing about her appearance seems unusual. It's only on closer inspection that doubts set in. Yes - she's a robot.

Nadine is an "intelligent" robot capable of autonomous behaviour. For a machine, her looks and behaviour are remarkably natural.

She can recognise people and human emotions, and make associations using her knowledge database - her "thoughts", so to speak.

At IMI, they are still fine-tuning her receptionist skills. But soon, Nadine might be your grandma's nurse.

Ageing populations

Research into the use of robots as carers or nurses is growing. It's not hard to see why.

The global population is ageing, putting strain on healthcare systems.

Although many 80-year-olds may only need a friend to chat to, or someone to keep an eye out in case they fall, increasingly the elderly are suffering serious ailments, such as dementia.

Friendships like that between Frank Langella's character and his robot carer in the film Robot and Frank could be a thing of the future

How can we provide quality care to address this array of needs? Many experts think an answer could be robots.

Nadine is being developed by a team led by Prof Nadia Thalmann. They have been working on virtual human research for years; Nadine has existed for three.

"She has human-like capacity to recognise people, emotions, and at the same time to remember them," says Prof Thalmann.

Nadine will automatically adapt to the person and situation she deals with, making her ideally suited to looking after the elderly, Prof Thalmann says.

The robot can monitor a patient's wellbeing, call for help in an emergency, chat, read stories or play games. "The humanoid is never tired or bored," says Prof Thalmann. "It will just do what it is dedicated for."

Nadine isn't perfect, though. She has trouble understanding accents, and her hand co-ordination isn't the best. But Prof Thalmann says robots could be caring for the elderly within 10 years.

Not ready for robots

US technology giant IBM is also busy with robo-nurse research, in partnership with Rice University, in Houston, Texas.

They have created the IBM Multi-Purpose Eldercare Robot Assistant (Mera).

IBM Research's Aging in Place Environment room

Mera can monitor a patient's heart and breathing by analysing video of their face. It can also see if the patient has fallen, and pass information to carers.

However, not everyone is ready for a robot carer, acknowledges Susann Keohane, IBM global research leader for the strategic initiative on aging.

This view is backed by research by Gartner, which found "resistance" to the use of humanoid robots in elderly care.

People were not comfortable with the idea of their parents being cared for by robots, despite evidence it offers value for money, says Kanae Maita, principal analyst in personal technologies innovation at Gartner Research.

Internet of things

Amid this scepticism, IBM believes its Internet of Things (IoT) research may prove more immediately valuable.

The firm is studying how sensors and IoT can identify changes in physical conditions or anomalies in a person's environment.

By recording atmospheric readings - such as carbon dioxide - in a patient's room, carers could understand a person's habits, such as when they eat lunch, or take a walk, without invading their private space. Carers could spot changes remotely and respond accordingly.

Ms Keohane says: "There's a real opportunity to create new innovative solutions, including the use of robotics and the Internet of Things, that will help people extend their independence, and enrich their quality of life."

Robo-pets

While widespread use of humanoids may be a long way off, robo-pets are already in use across the world.

Robotic Paro seal trials with dementia patients have had positive results

Developed in Japan, Paro is a therapeutic baby seal that has been shown to reduce the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia.

The seals respond to touch and are designed to make eye contact. About 5,000 are in use.

Clinical trials with dementia patients, conducted by Dr Sandra Petersen's team at the University of Texas at Tyler, found Paro improved symptoms such as depression, anxiety and stress. The need for symptom-related medication reduced by a third.

In some cases the results were even more remarkable. Dr Petersen says: "Some patients that were non-verbal began speaking again - first to the seal, then to others about the seal."

There are drawbacks to robo-pets, Dr Petersen admits - notably the cost. A Paro costs about $5,000 (£4,000).

There is also a reluctance by some in the medical profession to adopt non-pharmacological therapies.

Nonetheless, Dr Petersen believes the Paro may have a role in many health-related settings, as the seal's artificial intelligence allows it be programmed to adapt to a variety of behaviours.

"I think the Paro may have a role in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder, in neurocognitive rehabilitation with stroke patients, and with pain management or palliative care patients," she says.

"Autism-spectrum children may benefit from interaction with the seal."

'Ethical trade-off'

Inevitably, there are downsides to robotic solutions.

One issue, says Prof Sethu Vijayakumar, director of Edinburgh University's Centre for Robotics, is whether the spread of humanoid carers could lead to the increasing isolation of the elderly.

Nadine's robotic hand is remarkably life-like

"We have to ask: are [robots] isolating people more, or really helping people?" Prof Vijayakumar says.

The use of robotics also raises concerns about personal data issues, he says.

"The quality and personalisation of [robotic] services are directly proportionate to the amount of data you're willing to release to the system. Your data becomes a type of currency for access to better services.

"It's an interesting ethical trade-off. A very sensitive area."

Doubts aside, Prof Vijayakumar says the growth of robo-care is inevitable. "Demographics being the way it is, we will see significant use of robotics in dealing with the problems of old age."

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external

Click here for more Technology of Business features, external