Farewell to pay growth

- Published

- comments

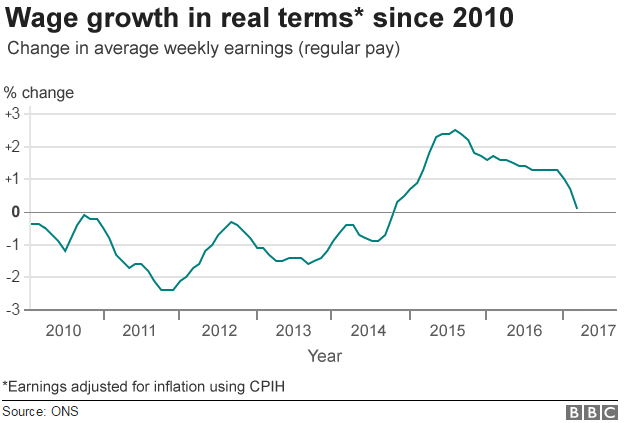

Income growth - or lack of it - has been one of the defining economic and political issues of the last decade.

Average weekly earnings are still £26 below where they were at their peak in 2008.

Employment levels are strong - which is economic good news.

But if people in work feel worse off year on year, then Number 10 knows it has a major issue to fix.

The reasons for Britain's wage stagnation problem are multiple.

The recession following the financial crisis raised the spectre of unemployment, meaning that holding on to your job became more important than asking for a pay rise.

As growth, demand and investment dried up following the banking collapse, inflation in western economies evaporated and in some sectors - such as food - price deflation became the norm.

The cost of living - the usual fuel for wage demands - stopped rising.

Then there is Britain's productivity problem, which will not return to its long-term growth rate of 2% until 2020.

Productivity measures the amount of value (outputs) created in the economy per unit of input - such as labour hours worked, materials used or capital investment spent.

Its increase is directly related to income: if productivity rises, wealth is created more rapidly than costs rise, and increased profit and wage rises are the result.

If productivity is poor - and the UK lags far behind America, France and Germany on this measure - that wealth is harder to come by.

Inflation surges

As Philip Hammond put it at the time of the Autumn Statement last November: "It takes a German worker four days to produce what we make in five, which means, in turn, that too many British workers work longer hours for lower pay than their counterparts."

By the time a British worker has earned £1, a German worked has earned £1.35.

When inflation is low or non-existent, stagnant real income growth is less of an issue for the people affected.

But over the past six months, inflation has risen markedly, from 1% in September to 2.3% last month.

Some of that is down to the fall in the value of sterling, but global inflationary pressures are also rising as more solid growth returns, as I've written before.

Today's figures from the Office for National Statistics reveal that earnings growth is travelling in the opposite direction - down to 2.2% last month from 2.3% in February.

And that, of course, is an average figure.

For some areas of employment - such as public sector workers - the picture is far grimmer.

Political dilemma

The Resolution Foundation says that more than a third of the workforce are already in sectors where pay is falling in real terms.

"Britain's brief pay recovery has come to an end," said Stephen Clarke, economic analyst at the think-tank.

"Forty per cent of the workforce are experiencing shrinking pay packets according to the latest figures, in sectors ranging from finance to the public sector. Many more will join them in the coming months as inflation continues to rise, with pay across the economy as a whole set to have fallen in the first three months of 2017."

Inflation is expected to jump again when the April figures are published next month - price rises associated with the later Easter holiday this year (increased air fares for example) will feed through as will plans by the major energy companies to raise prices.

At the same time, wage increases are set to continue slowing. It is likely that next month, falling real incomes will be back with us for the first time since September 2014.

As I have said before, Britain's income squeeze is one of the most difficult political and economic issues facing the government.

Many will argue that an economy that works for everyone would not be expected to be one where people are worse off at the end of the year than they were at the beginning.