What does it take to destroy a company's brand name?

- Published

What turns a corporate crisis into a company meltdown?

What changes a corporate branding disaster from being a costly and damaging affair, to one with fatal consequences for the company concerned?

How is it some firms have been able to bounce back while others are unable to survive?

Both the German car giant Volkswagen and South Korean mobile phone maker Samsung have been mired in controversy in recent times.

VW is still dealing with its diesel emissions scandal, and Samsung has had to face overheating phone batteries.

Yet both have put these corporate disasters behind them.

VW has just seen its pretax profits rise 44.3%, while Samsung's operating profits have gone up by 48%. Other firms have not been so fortunate.

Emissions scandal

In 2015, it emerged that Volkswagen had fitted illegal software to its diesel vehicles allowing them to cheat on emissions tests. It meant VW's diesel vehicles were able to emit up to 40 times the legally allowable pollution level.

VW's emissions scandal has so far cost it $25bn

The revelations came as a shock to many, and played havoc with VW's reputation as a seller of solid, dependable German cars.

The scandal sparked a global backlash against the firm, and multiple lawsuits.

VW has so far agreed to pay about $25bn (£19bn) to address US claims from owners, regulators, states and dealers - and it is under increasing pressure to pay up in other countries, too.

Yet this public relations disaster has not stopped VW from overtaking Toyota as the world's largest carmaker, and nor has it permanently hit its profit-making abilities.

As the scandal broke, VW put together a comprehensive plan to deal with it. It has acknowledged its wrong-doing - pleading guilty in the US as part of an agreement with regulators.

In the wake of the crisis VW has undertaken significant cost-cutting

At the same time, the group has embarked on a significant cost-cutting exercise - dropping unprofitable models - and is focussing on emerging markets and investing heavily in electric vehicles.

"One could argue that this crisis was a catalyst for VW," says Shwetha Surender, principal consultant at analysts Frost & Sullivan.

"The company has restructured itself in a way which it might not have done, had the emissions scandal never happened."

The scandal has cost VW billions, but could have cost it even more if it had mishandled things, she says.

"They might have been forced to sell-off their commercial vehicles division as well as a couple of their premium brands."

What VW did was clearly wrong but in the way it has dealt with the scandal "it has had a positive effect on the group", says Ms Surender.

Burning batteries

If you're one of the world's leading smartphone sellers, the last thing you want is to have to recall one of your flagship products.

A Samsung Note 7 handset caught fire during a lab test in Singapore

Yet that is just what South Korea's electronics giant Samsung was forced to do amid reports of fire-prone batteries.

Last September, Samsung recalled 2.5 million Galaxy Note 7 smartphones after complaints of overheating and exploding batteries.

The firm replaced the phones. However, that was followed by reports that those phones were also overheating.

The debacle cost Samsung about $5.3bn, and has been hugely damaging to its reputation.

Samsung has said it takes "responsibility for our failure to ultimately identify and verify the issues arising out of the battery design and manufacturing process".

That acceptance is a crucial part of its crisis management strategy, says Wayne Lam, analyst at IHS Markit.

Samsung has accepted its responsibility for the battery flaws

"What Samsung has done in handling the crisis is pretty textbook stuff. They have been upfront with consumers and investors - they have gone through their 'mea culpa' moments.

"From a financial perspective they have mostly put this behind them, though they still have to win back consumer trust."

Vital to winning back that trust is making sure there are no more mistakes. With its new Galaxy 8 phone, Wayne Lam says the firm has taken a conservative approach.

"They have tweaked the charging parameters and have been very cautious when it comes to the battery design, unlike the Note 7's battery which clearly didn't work."

Unreliable tests

For VW and Samsung the damage has been bad but survivable, but for controversial US blood-testing company Theranos its future is much more uncertain.

Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes once ranked as America's richest self-made woman

It pioneered tests that it said could detect cancer and cholesterol with just a few drops of blood obtained via a finger-prick.

Launched in 2003 it was said to be worth $9bn in 2014, but in 2015 a report by The Wall Street Journal claimed its device produced inaccuracies.

This led to an investigation by the US government's Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which later revoked the company's licence to operate in California and banned its founder Elizabeth Holmes from running a lab for at least two years.

The firm has since slashed its workforce by 40%, but analysts say it is unclear if it will ever be able to recover its reputation.

At least Theranos is still in existence, not so the US media and celebrity news website Gawker.

It filed for bankruptcy protection last year to avoid paying damages having lost a $140m lawsuit brought by former wrestler Hulk Hogan, after it published a video of him having sex with the wife of a friend.

Gawker had defended its right to publish the video as part of its celebrity news coverage. The court rejected the claim and the financial cost of losing forced Gawker to close down.

Doing 'a Ratner'

Yet nothing comes close to a firm being sabotaged by its own boss.

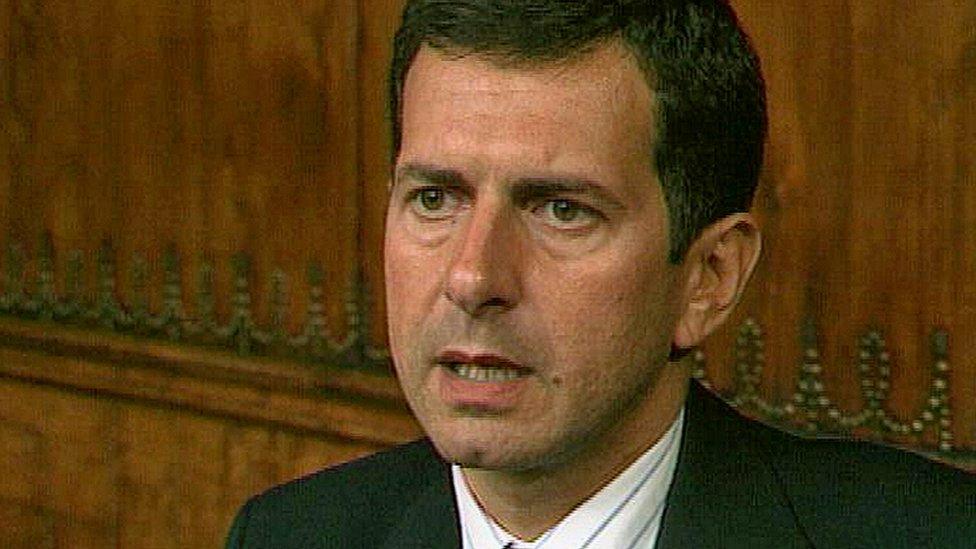

Gerald Ratner famously wiped £500m from the value of his own jewellery group, Ratners, with one speech in 1991.

Gerald Ratner, the boss whose speech ruined his own company

Referring to his firm's cut-glass sherry decanters, he said "People say, 'how can you sell this for such a low price?' I say because it's total crap."

For good measure he added that his stores' earrings were "cheaper than a Marks and Spencer prawn sandwich but probably wouldn't last as long".

These ill-judged comments accelerated the decline of Britain's biggest jewellery group.

It plunged into the red, closed 330 shops as customers stayed away in droves and changed its name to Signet Group two years later.

Mr Ratner has since bounced back and runs a successful online jewellery business, but his speech is still famous in the corporate world as an example of the value of branding and image over quality.

Such gaffes are now known as "doing a Ratner".

Follow Tim Bowler on Twitter@timbowlerbbc, external