Seeing the light: How India is embracing solar power

- Published

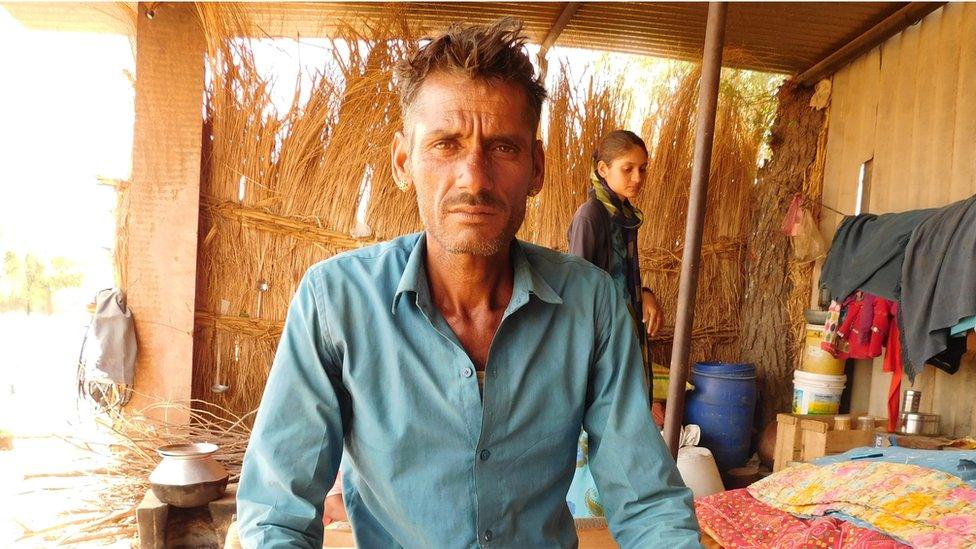

The addition of solar powered electricity has been a boon for the Choudhary family

India unveiled the world's biggest solar farm earlier this year and has quadrupled its solar capacity in the last three years, bringing electricity to millions of off-grid households. But what are the innovations that could see solar replacing fossil fuels completely?

Rameshwarlal Choudhary, a 45-year old farmer, and his wife Dakha, 40, live with their two children in a small shack near the village of Solawata in India's Rajasthan.

Their home has thatched walls, a tin roof, and one side is completely open to the elements.

Until six months ago, they were part of the 44% of India's rural households who lack electricity.

Now, through a 40-watt solar panel perching on a tree branch outside the hut, they have enough power for three lights: one inside the house, one in the fields, and one on a tree above the roof.

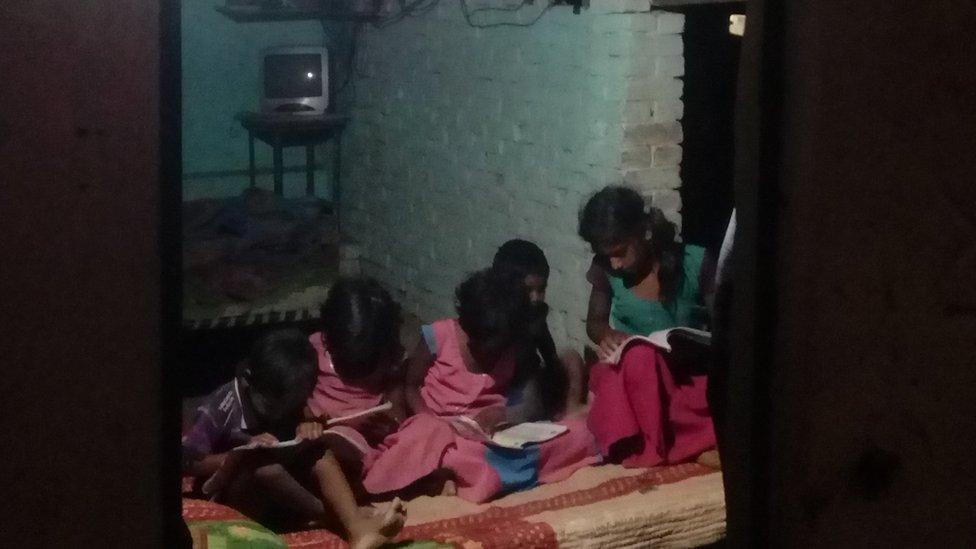

"With the extra light we can study until 10 pm," says their daughter Pooja, a 17-year-old student.

And her parents can farm and milk their cows beyond sunset - around 5pm - for the first time.

"The light also helps keep snakes, rodents, and scorpions at bay," says Ramjilal, their 20-year-old son who is also a student.

Thanks to electricity, children can now carry on their studies at night

This one small example is emblematic of how India is going solar in a very big way.

In November, the country unveiled the world's largest-ever solar farm at Kamuthi, in Tamil Nadu.

It stretches across 2,500 acres, and its 2.5 million solar modules are cleaned each day by a team of robots, themselves solar-powered.

While countries like Britain and Germany have seen new solar installations slow after the withdrawal of government subsidies, India and China are ramping up their installations.

India quadrupled its capacity in the last three years to 12GW (gigawatts) - 1GW can power about 725,000 homes.

This will almost double again this year, with India adding 10GW in 2017; another 20GW is in the pipeline.

China is installing solar panels at a similar clip; its capacity leapt to 77GW last year, up from 43GW.

The Kamuthi Solar Power Project in Tamil Nadu is the largest solar farm in the world

As recently as 2010, there was only 50GW of solar capacity installed in the entire world.

"This installation of solar power is much higher than anyone could've believed just a few years ago," says Josefin Berg, senior analyst for the IHS solar research group.

"The cost of the technology has dropped much faster than anyone anticipated," she says, "but the main decline has been in the technology advances."

Solar panels are just not that efficient.

A major problem is that about 35% of the sun's light is reflected off the panels rather than being absorbed and converted into electricity,

So could biomimicry - copying structures already found in nature - help the panels become more light absorbent?

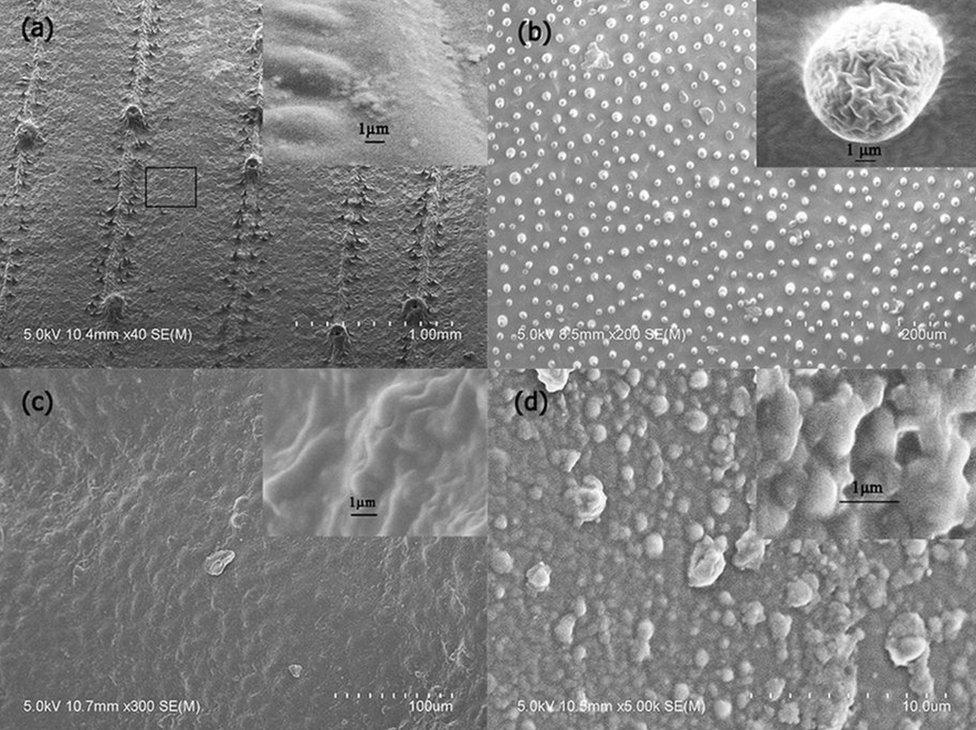

What different leaf structures look like under an electron microscope

One research team in Finland thinks so. It has been studying leaf structures to find out how they do it.

Prof Marko Huttula and senior research fellow Wei Cao at the University of Oulu studied 32 different types of leaf structure to see which absorbed light the best.

"Corn seems to be the winner for light absorption," says Prof Huttula. "That kind of makes sense because it is very fast growing."

Using what they'd learned, the pair designed a polymer coating featuring patterns of what Dr Cao calls "nanodots". This polymer is then applied on top of silicon cells.

So far they have succeeded in reducing the percentage of light lost through reflection from 35% to 12%.

Decreasing wasted light this way increases solar panels' energy output by up to 17%, they claim.

Now they are working on scaling up the process with collaborators in China.

Even with costs of solar cells dropping, there are pretty large leaps forward in efficiency needed before solar energy can broadly supplant fossil sources, says Dr Ross Hatton, an associate professor of physical chemistry at Warwick University.

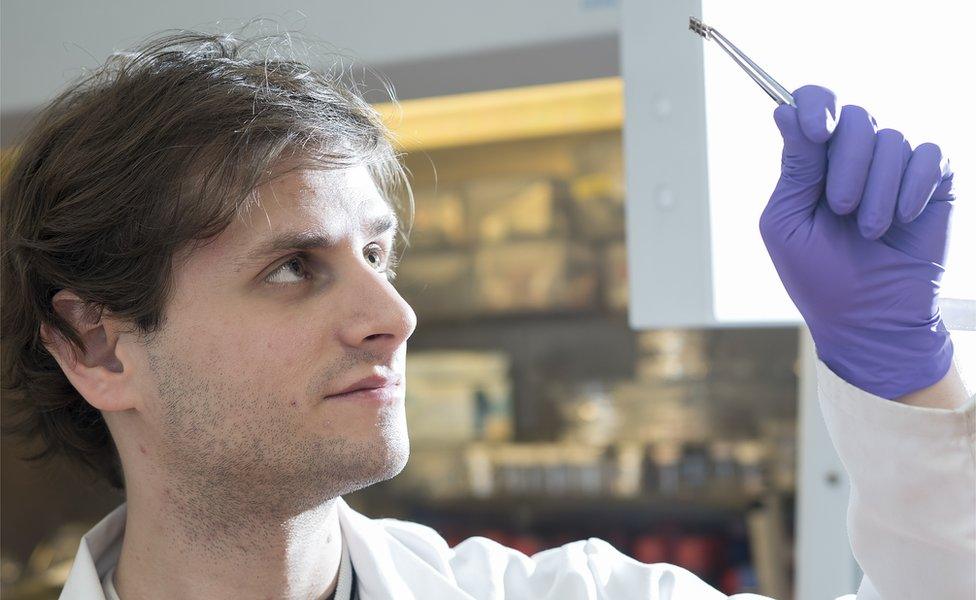

University of Warwick PhD student Kenny Marshall holds up a perovskite solar cell

Today's commercial solar cells convert only about 16% to 20% of the sun's energy into electricity.

Solar cells based on semiconductors with both organic and inorganic parts - called perovskite solar cells - might boost this up to around 30% if combined with conventional silicon technology.

Perovskites can also be made as flexible, lightweight films, meaning they are both cheap and easy to install in a wider variety of places.

But a downside is that they tend to disintegrate in humid conditions.

"I would say that there would be a very significant cost advantage over silicon, but it's also about the utility - silicon can't be used on the tops of automobiles, or on the cover of your laptop," says Dr Hatton.

Also, they "could be fabricated using a roll-to-roll process - it's how you print a newspaper - and is a very well established technology," he says.

Several university spin-offs, like Oxford PV and Eight19 in the Cambridge Science Park, have said they aim to market perovskite solar cells this year.

Another problem with solar is that at a domestic level, installing it is still a cumbersome process - and many householders don't much like how the panels look.

The Smartflower opens up and tracks the sun...

...then folds itself up at the end of the day or in bad weather

This is why Tesla boss Elon Musk unveiled a new design for solar panels that resemble traditional roof tiles.

And Austrian start-up Smartflower has designed a neat, all-in-one solar unit that sits in your garden, tracks the sun like a sunflower, and folds itself up for protection at the end of the day or in poor weather.

The Smartflower, which costs from £13,560 ($17,660), produces enough electricity to power a standard household of four people, but needs five cubic metres of space. So the company is developing a smaller version for people with less external space.

They have sold the device in Europe since 2014, and last year in the US as well.

The firm is also developing an "internet of things" capability for the product so that the Smartflower can switch household appliances on and off depending on how much solar electricity is available.

With the cost of solar continuing to drop around the world and efficiency improvements - however modest - coming through, the future of this renewable tech looks bright.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external