Will Opec extend output cuts in bid to push up oil prices?

- Published

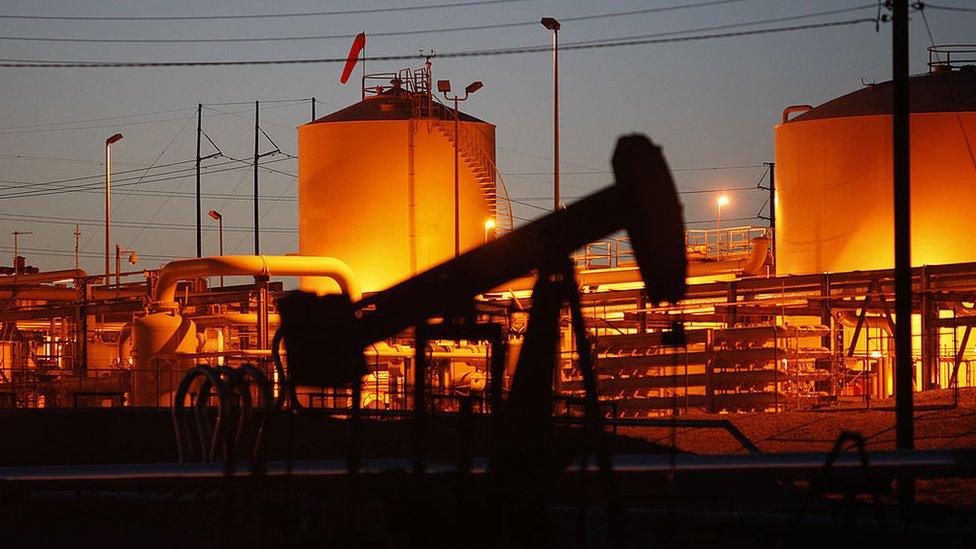

US shale oil production has become a major competitor for Opec

Crude oil is too cheap for the taste of many producers.

Energy ministers from Opec, the oil exporters' group, are meeting at their headquarters in Vienna to do something about it.

They will be joined by delegates from some oil suppliers outside the group.

On the agenda: whether to extend the oil production curbs agreed last year that are due to expire next month.

There is widespread support in the group for taking this step, and members could also discuss reducing the ceiling on oil output even further.

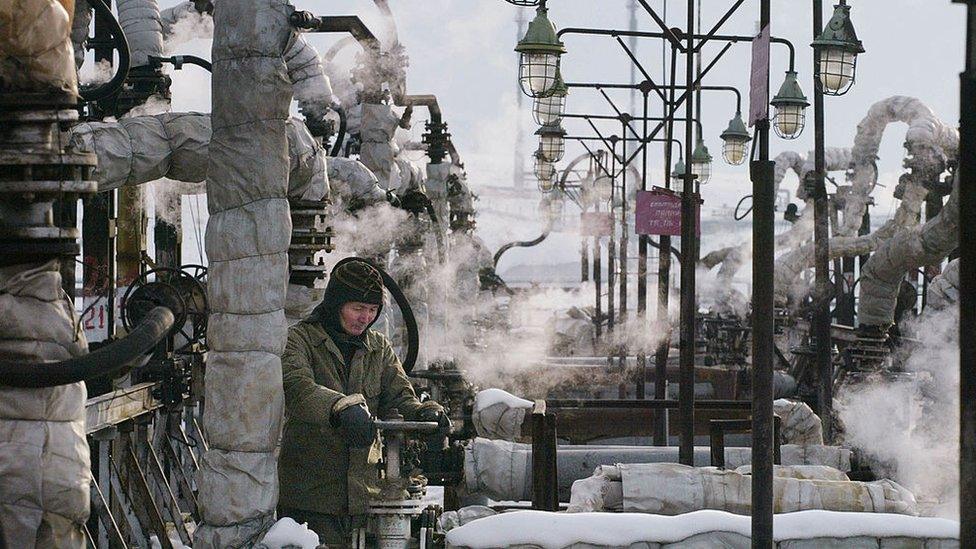

Saudi Arabia and Russia want to extend existing production curbs

The formal meeting happens on Thursday but key bilateral talks will take place in Vienna hotels ahead of the official gathering.

Key deal

Two key players have already agreed that they want to extend the existing limit until March next year: Opec's biggest producer, Saudi Arabia, and Russia, the biggest exporter outside the organisation.

The problem for Opec and other oil exporters started almost three years ago, when the price of oil began to slide.

North Sea Brent crude oil, which is widely used as a price benchmark, hit a high of around $115 (£88) a barrel in June 2014 but by the end of the year it was half that amount.

The price of North Sea Brent crude oil is a significant benchmark for the world's oil industry

While Opec members may not sell Brent crude, the prices they get for their oil do move in parallel to this benchmark.

And it got worse still from OPEC's perspective; in January 2016 the price of Brent fell below $28 a barrel.

Since then it has rebounded, but has not got much beyond the mid-$50s per barrel.

That partial recovery has taken some of the strain off Opec members' finances. Many have also responded with cuts to government spending.

But they could really do with a stronger price recovery.

What and who is Opec?

Formed in 1960, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec) coordinates the energy policies of member countries, who produce about a third of the world's oil

Its members include Algeria, Angola, Ecuador, Gabon, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, UAE and Venezuela

A number of other major oil-producing nations such as the US and Russia are not Opec members

To take one example; last year Saudi Arabia had a deficit in the government's finances equivalent to 17% of national income. This year the IMF projects it will be 10%.

It's a substantial improvement but still far too high for the long term.

Surpluses generated in times of higher prices in the past mean the Saudis do not, however, have an imminent problem of unmanageable government debt.

Iraq's Jabbar al-Luaybi (right) says his country will also extend production cuts

What Opec and a group of other oil exporting countries including Russia have already done is cut back production in an effort to boost prices. They agreed that last December, external.

The reduction was almost 1.8 million barrels per day - equivalent to about 2% of global oil production.

Widespread compliance

Often in the past Opec countries have agreed to cut production but failed to comply with their own commitments. The temptation is for individual countries to cheat and sell more while hoping that others will cut production and push prices higher for all.

This time, however, Opec discipline has been remarkably strong. The International Energy Agency (IEA) a rich countries' watchdog, estimates compliance with the restraints is at more than 95%.

That said, the agreement has not been very effective. Today the price is actually a few dollars less than it was on the day the deal was done. Without the cuts, though oil might have been even cheaper.

Unlike past agreements, this time Opec members have largely stuck to their agreed output curbs

OPEC members do have a relatively new problem: the American shale oil industry. It has grown from very little 10 years ago, to become a major player.

In fact it made an important contribution to the abundant supplies of crude oil that were behind the price fall that began in 2014. In 2005, US crude oil production covered a third of the country's needs, now the figure is more than 60%.

In the early stages of the price fall Saudi Arabia appeared to be willing to live with the decline in the hope that it would put pressure on US shale producers and force many out of business.

It was uncomfortable for America's oil industry but it proved to be more resilient than the Saudis probably expected, and their producers were very effective at reducing costs.

The amount of oil held by refineries and governments is at record levels in some countries - so an immediate price rise is less likely

Total US oil production did decline in 2016, but it is rebounding this year.

Stock levels

Opec's production cuts have made space for other producers in non-member countries and the recovery in prices from their lows of early 2016 has eased the financial pressure.

One manifestation of the abundant supply is the fact that stocks of crude oil held by refineries and governments are well above normal levels; a new historical high in the rich countries in March, according to the IEA.

The objective shared by Opec and Russia is to get stocks down to the average level of the last five years.

The signs are that Opec members are mostly well disposed to continuing the cuts beyond next month's planned expiry. There may well be some debate about how long to extend them, and there have been reports that some would like to make the cuts deeper.

Unlike Russia, non-Opec member Kazakhstan wants to increase production

Outside Opec, Russia is in agreement but Kazakhstan wants to increase production, while others have been holding discussions with Opec countries.

Assuming they do take extend the production limits, what will be the impact on oil prices?

They may stay towards the upper end of the recent range - but it will take a while for those stocks of crude oil to come down to levels that could support a stronger rally.

Opec's likely action could certainly ensure that prices don't take a renewed dive but the prospect of a powerful surge in prices is not strong.

US sell-off

There is a new complication for the producers' calculations. President Trump's budget plan includes a proposal to sell half the oil in the US government's emergency reserves, the strategic petroleum reserve, external, starting from the next financial year.

The shift to electrically-powered vehicles poses a long-term challenge for Opec

It is just a proposal at this stage but it has still been enough to move international oil prices down.

Yet in the longer term, the weakness of oil prices does perhaps contain the seeds of its own reversal.

The low prices have undermined investment in new production capacity in the last two years, which in turn means that there could be a supply crunch. The IEA, external has warned this could come sometime after 2020.

In the even longer term, the big question for Opec is whether a shift away from oil-based transport fuels - in favour of electrically-powered vehicles, for example - will cast a shadow over the viability of their natural resources.

- Published15 May 2017

- Published5 May 2017

- Published13 April 2017

- Published26 March 2017

- Published14 March 2017

- Published30 November 2016