The restaurateur who puts hospitality above food

- Published

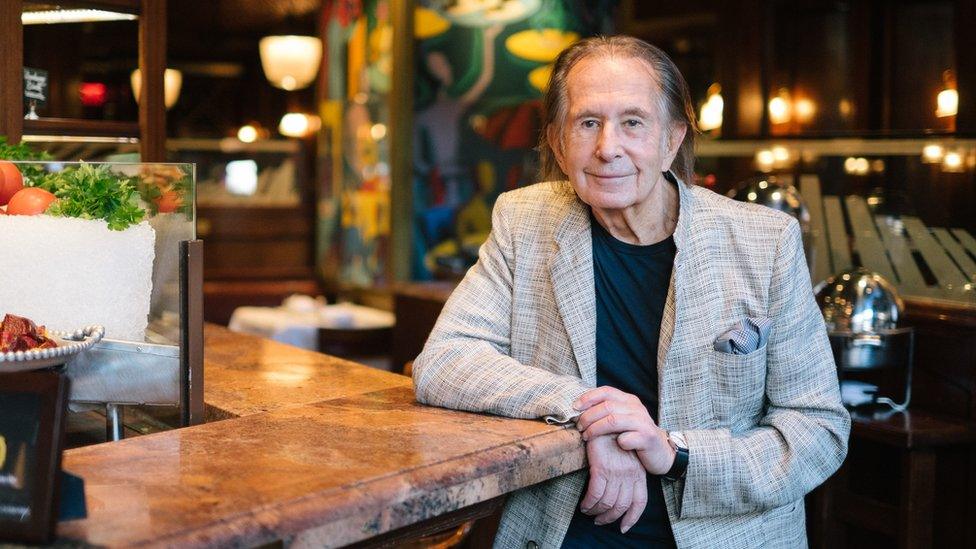

Shelly Fireman's career as a restaurateur spans more than five decades

Like other great success stories, Sheldon Fireman's started with a sense of ambition, an understanding of the local culture, and nothing to do on a Friday night.

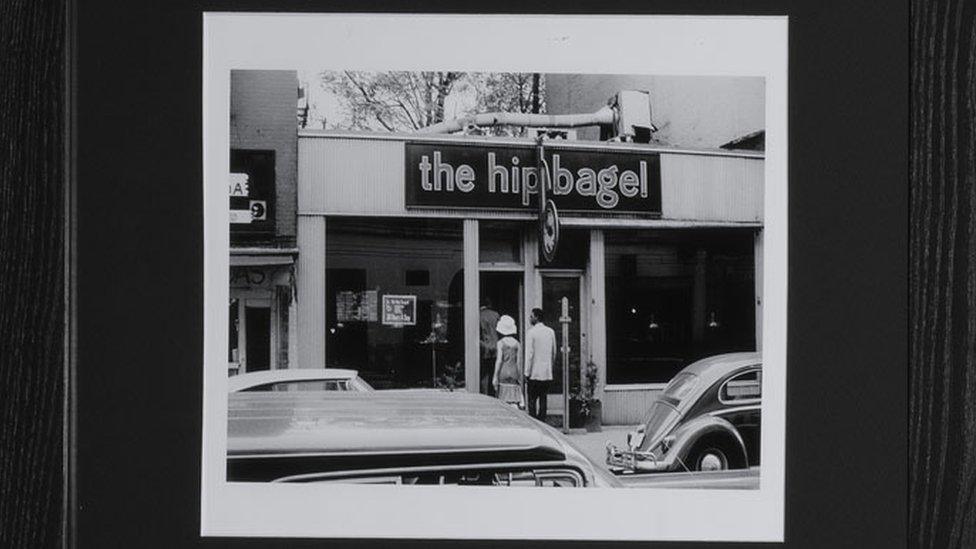

Hanging out in the Greenwich Village neighbourhood of New York in the 1960s, Mr Fireman - Shelly to his friends - got the idea to open an all-night cafe specialising in serving breakfast food. It would be called the Hip Bagel.

"I fell in love with my idea," says Mr Fireman, who wanted to create a place that was fun to hang out and be seen in at all hours.

He opened The Hip Bagel in 1964 at a cost of just $500 (£385).

For the next 14 years the establishment lived up to its name - attracting celebrities such as Woody Allen and Barbra Streisand.

It also propelled Mr Fireman towards becoming one of New York's preeminent restaurateurs.

He was in his 20s then. Today, 53 years later, his company, Fireman Hospitality Group owns nine restaurants in New York and Washington DC that continue to attract celebrities, and which brought in nearly $60m (£47m) in 2016 alone.

In the 1960s The Hip Bagel attracted New York celebrities looking for a late night bite

Mr Fireman grew up in The Bronx, New York, and started his career in the garment business before switching to hospitality.

"I had no mentors [in the garment business]," says Mr Fireman, "and I was impatient to be successful in life."

Risky business

That impatience drove him towards a risky industry.

About 60% of restaurants in the US close in their first three years, and in New York the challenges are particularly acute. Rents are high, you need to attract both locals and tourists, and new establishments are more likely to get negative reviews.

There is also competition from approximately 24,000 other eateries around the city.

Decades into his career, Mr Fireman keeps moving forward with new ideas

In 1974 Mr Fireman opened his second restaurant, Cafe Fiorello, just blocks from Central Park.

Like The Hip Bagel, the focus was on hospitality. It's a theme he's carried through to each successive restaurant, be they fine-dining establishments like Trattoria Dell'Arte or casual restaurants like the Brooklyn Diner.

Customers are more likely to remember how the place made them feel, Mr Fireman argues, than the food that they ate.

"Everyone has their favourite pizza. Who am I to say what the best is?" he explains. "But hospitality they remember."

Adam Platt, a restaurant critic who has covered New York's food scene for more than 15 years, says that for old-school restaurateurs like Mr Fireman, running a restaurant is a lot like putting on a Broadway show.

"He's really a theatrical producer. The Brooklyn Diner isn't really a diner and it's not in Brooklyn, but he puts together this successful production," says Mr Platt.

The Brooklyn Diner on 57th Street is Mr Fireman's tribute to casual American dining

While Mr Fireman likes to jump from one type of restaurant to another, there are characteristics common to all his establishments.

Each tends to be large and to have a clearly defined concept. Prices are also high, but not out of line with nearby competitors, and each relies heavily on its location to attract a high volume of customers.

The Brooklyn Diner, for example, serves on average 1,200 customers every day.

Mr Fireman has a "nose for location and for matching that location to the appetite of the neighbourhood", says Mr Platt.

In 2010, the Fireman Hospitality Group also opened its first restaurant outside of New York - an outpost of its steakhouse, Bond 45, just outside Washington DC.

More The Boss features, which every week profile a different business leader from around the world:

How Bite Beauty is building an all-natural lipstick business

The millionaire boss who admits he had a lot of luck

The man who built a $1bn firm in his basement

While Mr Fireman has been reluctant to work with celebrities, he does rely on investors for financial support and business guidance.

He took on his first investors in 1992 when he opened Trattoria Dell'Arte, which is located opposite the famous concert venue, Carnegie Hall.

Since then he has taken on outside investors for every new project, giving up 10%-15% of the ownership, depending on the restaurant.

Trattoria Dell'Arte was the first of Mr Fireman's restaurants to take on outside investors

"Investors are wonderful, but you have to be able to hear their criticism," says Mr Fireman.

Disagreeing with the businessman, who has been described as outspoken and eccentric, can be daunting.

Stephen Zagor, the former manager of Trattoria Dell'Arte, says those who plan to tell Mr Fireman he's wrong better come armed with information to back it up.

"He loves a good verbal joust. If you don't have your information together he will pick you apart," Mr Zagor says.

Learning from failure

But Mr Fireman himself admits that not every project has been a success.

A restaurant on the Upper East Side of Manhattan gave him particular difficulty. Over the course of 15 years, it failed to make a profit, despite repeated redesigns, name changes and menu updates.

A partnership to launch an outlet of the Brooklyn Diner in Dubai also failed. According to Mr Fireman, it failed to live up to the quality his partners had promised to deliver.

"You're never going to do it perfectly; if you can't take the pain of mistakes you can't do this," he says.

With around 24,000 eateries in New York, there is a lot of competition facing Fireman group restaurants like the Redeye Grill

The company has also faced criticism from employees who complain that the intense focus on hospitality means the mantra "the customer is always right" can sometimes be taken too far.

A 2006 lawsuit also pitted the Fireman Hospitality Group against employees who claimed that they had been underpaid and wages had been withheld. The company settled the case out of court, paying $3.9m (£3m).

None of this has shaken Mr Fireman from his desire to open more restaurants and test new concepts. After more than 50 years in the restaurant business, he is as hungry for success as ever.

He is currently working on a new idea for a fast casual restaurant that he plans to launch in New York and spread throughout the US.

"Every time I think about it and improve on it and tweak it, it's like I'm finding gold," says Mr Fireman.

- Published22 May 2017

- Published1 May 2017