Are 'McJobs' really history?

- Published

- comments

Deliveroo classes its riders as self-employed "independent contractors"

It was the Washington Post that first coined the term in 1986.

"The fast-food factories: McJobs are bad for kids" a headline announced over a report about thousands of teenagers employed in McDonald's US kitchens.

The term took hold, to such an extent the Oxford English Dictionary still defines McJobs - 30 years later - as a catch-all for "unstimulating, low-paid jobs with few prospects, especially ones created by the expansion of the service sector".

Job insecurity is a common feature.

Fretting about "McJobs" has returned as the world of work changes rapidly.

And whoever wins the next general election will need to deal with this most fundamental of changes, away from the world of the nine-to-five, permanent job with a single employer, and towards a world of flexibility where people and technology become more entwined.

The very wealth of our economy depends on riding this wave - a global trend - successfully.

One of the first challenges the new prime minister will face is how to react to the most significant inquiry into the new world of work at present being finalised by Matthew Taylor, the head of the Royal Society of Arts.

He was commissioned to undertake the review by Theresa May last autumn, and has said he will deliver the report to Number 10 shortly after 8 June.

Much of this new world of work is said to be negative.

The number of zero-hours contracts - which offer no guaranteed work - has grown from 143,000 in 2008 to over 900,000 now.

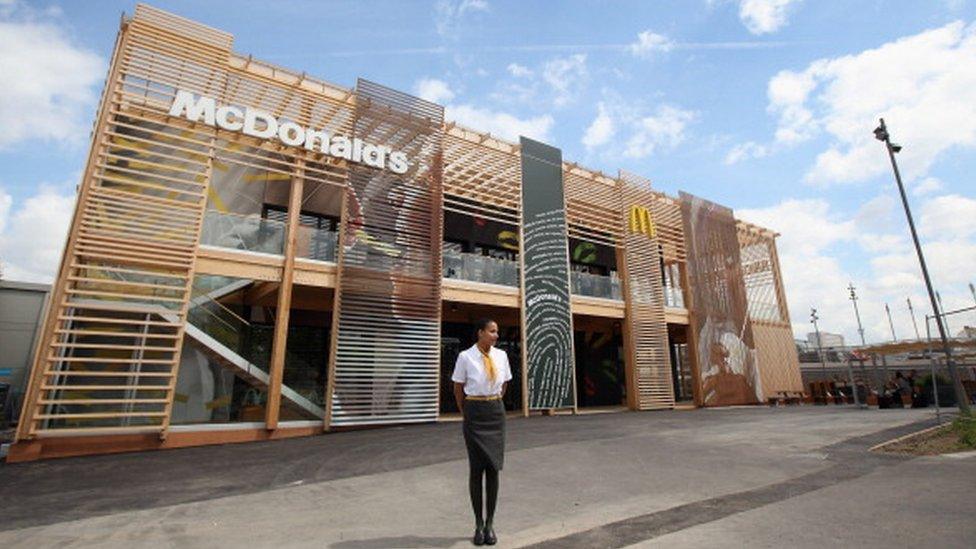

The term McJobs was first used in the 1980s to describe teenagers employed in McDonald's US kitchens

Alongside that development comes the expansion of "self-employment" which has accounted for 45% of all employment growth over the same period (although it is worth remembering that more than 80% of working adults are still in more traditional, permanent employment).

Are zero hours contracts simply the return of "casualisation", where employees are at the beck and call of profit-hungry and often unscrupulous employers?

Or a nod to new, modern needs for flexibility, so that work can be balanced with the rest of life?

Is hiring from the new army of the "self-employed" simply a way of businesses avoiding tax and pension responsibilities and bypassing the rights - such as holiday and maternity leave - guaranteed to full time workers?

Or a nod to individual autonomy, where people work to their own rhythm and receive just reward for their entrepreneurial flair?

Of course, it depends which businesses you speak to.

Especially if it's the business that was the original butt of the McJobs attack - McDonald's.

"We have restaurant managers that look after 100 people, they are running businesses over £2m [in revenues] and they are responsible at a young age for their fortunes and their future," Paul Pomroy, the chief executive of McDonald's UK, told me.

Many of those managers started in the kitchens - not actually flipping burgers, it turns out, as machines fry the beef patties on both sides and there is no need to turn them over.

Indeed, when I put it to one manager, Liz Stephenson, that working in McDonald's is not all "flipping burgers", she replies archly: "I've never flipped a burger."

Some fear that automation could increasingly replace workers in the future

Snobbery is one word that comes to the mind of people like Liz when they consider how some view a career like hers, which started behind the counter on casual hours when she was at school and now involves being the company point person for restaurant managers who are running businesses with revenues counted in the tens of millions of pounds a year.

We have long had a rather romanticised vision of manufacturing jobs - even low-skilled ones - and have yet to fall in love with the service economy - such as retail - despite the fact it makes up the vast proportion of our economy.

"McDonald's offer training and a real career," Ms Stephenson (who is off to Chicago to receive a global company award for her achievements) tells me. "I've heard all the jokes."

Whatever the protestations of businesses which say they have worked hard improving their employment practices (McDonald's offers zero-hours workers rights to sick and holiday pay and has never demanded employees abide by "exclusivity clauses"), chief executives know controversies over companies such as Sports Direct and Uber can muddy all their reputations.

"Businesses take decisions that do damage," Mr Pomroy said, making clear he is not referring to any specific examples.

"Businesses in the modern world need to open up more, be transparent and be honest about how they treat their people and how they treat their customers.

"The internet has such a vast array of information, you can't sit back and hide anymore and not be front foot."

He added: "People up and down our workforce want to be treated with respect, they want a fair chance, they want progression, they want to have fun when they are working, they want to feel part of a team.

McDonald's says it will hire more people in the UK

"I want to be able to walk into our staff rooms and look people in the eye and know we are treating them fairly - whether it is the 16-year-old school leaver or the 35-year-old mum who is using our flexible contacts to interweave with childcare."

Mr Pomroy dismisses claims that zero-hours contracts, for example, are simply a method for firms to keep people in insecure, low-paid work.

As I wrote last month, when offered the chance to move on to fixed-hours contracts, 80% of McDonald's staff affected said they preferred zero-hours.

Automation ahead?

The other big, robotic, beast in the room when it comes to the new world of work is technology.

The fear is that while we worry about zero-hours and self-employment, artificial intelligence and computers that can crunch "big data" in the blink of an eye are going to replace millions of us in the workplace.

For services industries like his, Mr Pomroy is not so sure.

"Since we have introduced technology - you can place your order on giant screens - it hasn't actually saved us labour in terms of reducing the number of people we need," he said.

"We've actually used that as a springboard to put more people out in the dining area, so giving hospitality.

"We've introduced table service. Using technology to enhance the customer experience is what is critical - not cutting the number of jobs we offer.

"So since we have been introducing technology, we've recruited a further 5,000 people - taking our total workforce to 115,000."

That jobs growth will continue, he insists, revealing plans to recruit 2,000 to 3,000 jobs a year.

"We have over half our restaurants open 24 hours a day, five days a week, and there is still opportunity to extend the number of restaurants that operate 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

"We are also a growing business. We have had 11 years of consecutive sales growth. I've got no plans to slow that down."

In 2007 McDonald's launched a campaign to have "McJobs" removed from the dictionary.

They are still trying.

"I would love it to go," Mr Pomroy said.

"Not for me, I'm the CEO. It's more for the 115,000 people that work in our restaurants; they would love it to be removed."

McDonald's spawned the "McJobs" tag in the 1980s and insists it has moved on.

Mr Pomroy's problem is that other businesses could now be taking on the mantle as the new world of work throws up a very 21st century challenge.

- Published23 May 2017

- Published11 May 2017

- Published25 April 2017