Could you cope with smartphone rationing?

- Published

The use of child labour at cobalt mines has attracted criticism from human rights groups

A number of metals are crucial components in a range of technologies, from smartphone batteries to electric cars. So could a market shortage and spiralling prices put the brakes on the global tech industry?

Cobalt has been used for thousands of years to give a deep blue-ish hue to pottery, paint and jewellery. But more recently, it has become a crucial metal used in the batteries powering millions of tech gadgets, including the electric cars made by Tesla and others.

About half of all cobalt demand comes from the expansion of electric vehicle production and development worldwide.

The problem is, we can't get enough of it. No wonder its price has doubled in the last year alone.

"We are definitely entering a period of deficit and that will start this year," says Lara Smith, managing director of Core Consultants, a commodities researcher.

"In 2016, the supply of cobalt was about 104,000 tonnes and demand was about 103,500. The hybrid and electric vehicles are in a nascent growth phase, so as we continue along this track we expect there to be a greater and greater deficit."

Will the growth of electric vehicles be slowed by a shortage of cobalt?

Only 2% of cobalt is mined directly - 98% of it is produced as a by-product of nickel and copper mining. Unlike other battery metals like lithium, cobalt is quite rare and its quality can vary geographically. About two thirds of the supply comes from Africa's Congo region.

It's little wonder then that First Cobalt Corporation in Toronto recently invested in seven large areas of land in the Central African "copperbelt" with the intention of finding more copper and cobalt reserves in the ground.

"Electric vehicle market penetration around the world is projected to grow 26% this year alone," chief executive Trent Mell tells the BBC.

"We are predicting a growth rate in cobalt demand of 5% per year for the next five years. On the supply side the pipeline of new production is pretty scarce.

"To bring up a mine to full production can take up to 10 years."

First Cobalt Corporation boss Trent Mell surveys potential cobalt mine land in central Africa

Efforts to mine cobalt in North America are under way, but any increase in US and Canadian production is expected to be small compared with future anticipated demand globally.

And the Congo mining region has also been under scrutiny as it deals with accusations of child labour and other human rights abuses, summarised in an Amnesty International report last year, external.

In other words, ramping up supply could take quite some time.

And this shortage in the supply of "technology metals" is not limited to cobalt.

Many modern electronics rely on them - neodymium, praseodymium and dysprosium to name but a few - which make them faster, lighter, stronger, and more energy efficient.

If the metals our gadgets need become hard to get hold of, you could wait years for that upgrade

These rare earth metals along with minor metals such as lithium and tantalum are now just as important as the traditional base metals and precious metals.

"The colour red on a MacBook Pro screen is made from europium; the colour green is because of a metal called terbium; touch screen technology relies on indium," explains David Abraham, author of a book called The Elements of Power.

"A lot of these metals have only been discovered in the past 100 years. We've had a long time to play with copper and iron. But we are just beginning to understand the power of these newer materials."

More Technology of Business

Unlike cobalt, most other technology metals are not rare. It's getting them out of the ground and in to manufacturing locations that's tricky.

Again, most are by-products of other base metal mining activity and involve additional complex chemical extraction processes.

China dominates the mining and production of many technology metals, due in part to weak environmental codes. It produces 100% of the world's dysprosium for example.

While there is lots of talk among other nations - notably Australia - about starting their own mines and processing centres, there is little real appetite for it, believes Mr Abraham.

A lot of countries don't want to open new mining and processing facilities because they are deemed "dirty" and environmentally unpopular, he says.

The alarm bells for tech companies sounded in 2010-11 when the prices of several rare and minor metals sky-rocketed.

"There was a major price spike in some of these materials," says Gareth Hatch, co-founder of consultancy group Technology Metals Research.

"Some went up anywhere from 300% to 1,000% in price for a variety of reasons, and that alerted everyone to the fact that we are dependent on these materials and they are all coming from China - and that could be a problem."

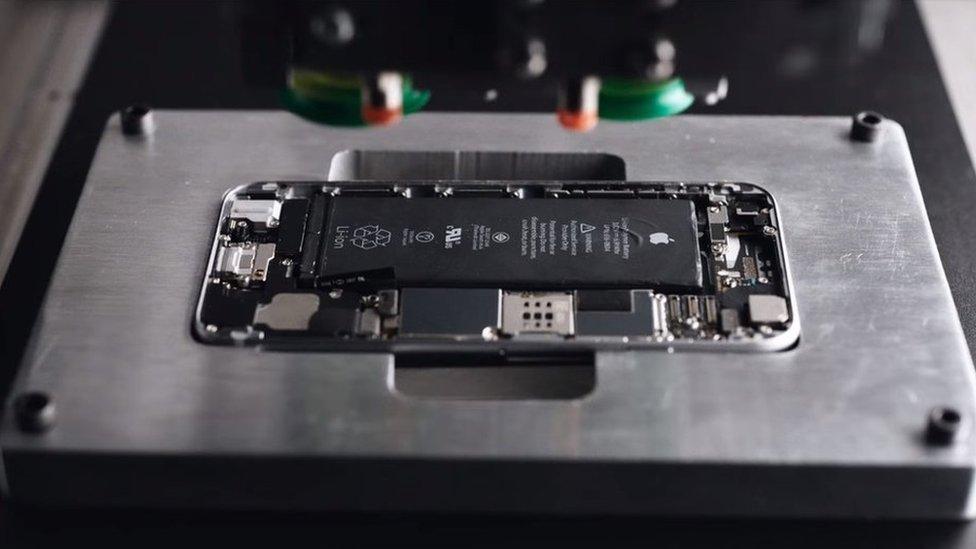

Apple's Liam robot disassembles the iPhone to recover metals such as cobalt, lithium and gold

Although prices of most elements have normalised again, the fact that China has so much influence over supplies is a cause of increasing concern.

Political and economic differences between China and the West are a constant conversation topic in the US and elsewhere. Find yourself on China's "less than co-operative" list and you could potentially see your essential supply of tech metals dry up overnight.

One way of breaking China's stranglehold is to recycle the materials.

Apple is a leader in this field, marshalling a line of robots called Liam to disassemble used iPhones in a few seconds, enabling recovery and reuse of many of the materials used, such as cobalt, indium and gold.

But it's hard for the technology companies to predict what will happen in a decade from now.

If supplies of crucial elements dwindle, prices of new gadgets are likely to rise if supply cannot match demand.

Perhaps then, we may have to learn to live with with our existing gadgets for longer.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external

Click here for more Technology of Business features, external