Where many of the clothes you throw away end up

- Published

Torn or damaged clothes from the UK, US and other countries often end up in Panipat in India

Ever wonder where your clothes go after you discard them?

In Western countries, when you donate clothing to charities via shops, collection bags, or clothing banks many are given to those in need or sold in charity shops to raise funds.

But what happens to torn or damaged clothes, or items that no one wants to buy?

Often, they are sent to India, joining a global second-hand trade in which billions of old garments are bought and sold around the world every year.

Specifically, to Panipat in northern India which is known as the world's "cast off capital".

Every day hundreds of tonnes of clothes from across the UK and the US, and other countries, arrive in Panipat.

Outside the town, you can see long queues of trucks waiting to get in. They come here from the port town of Kandla on India's western coast - where ships bring containers full of worn clothes and textiles from all across the world.

The businessmen here call them "mutilated" clothing.

At Shankar Woollen Mills the clothes are first sorted by colour

India is the top importer of used clothes, beating countries such as Russia and Pakistan, according to the most recent data available, external.

In India, used clothes can be imported under two different categories - one is mutilated and the other is wearable.

To protect local garment manufacturers in India, importers of wearable clothing need a licence from the government. This licence will only be issued if the buyer guarantees the clothing will not be sold in India, but is instead re-exported.

However, the bulk of Indian imports of used clothing happen in the mutilated clothing segment, which doesn't require a licence.

In one of the recycling mills, Shankar Woollen Mills, I have to walk over hundreds of colourful buttons on the floor as I try to find my way.

It's humid and the piles of woollen clothing seem to be adding to the heat on this already hot summer day.

All around me, there are mountains of jackets, skirts, cardigans, berets and what looks like school uniform. From high-street brands to luxury labels - most clothes donated to charity end up here.

Piles of torn and used clothing that would have otherwise ended up as landfill.

Workers are bent over large blades, shredding clothes. They are ripping everything apart to remove zippers, buttons and labels.

The recycled fabric is largely used to make blankets

The clothes are then stored in large piles according to their colour: reds, blues, greens and a lot of black. This is the first step of breaking down the clothes into yarn before they are rewoven into beautiful fabric.

They are then processed in batches with similar coloured garments.

"We process it in machines which does what the human hands can't - rip the fabric into smaller rags.

"This is then fed into a bigger machine which mixes wool, silk, cotton and any man-made fibre like polyester and feeds into a carding machine which starts to spin into yarn," says Ashwini Kumar, who runs Shankar Woollen Mills shows me what happens next.

Every three tonnes of fabric produces around 1.5 tonnes of yarn, which is woven back into what's called "shoddy" fabric.

The shoddy fabric is then used largely to make blankets.

"They are used as relief material distributed during disasters - so at every tsunami, cyclone or earthquake - anywhere in the world, you see these blankets being distributed," adds Mr Kumar.

Or the fabric is sold as cheap blankets for the poor costing under $2 (£1.55) each.

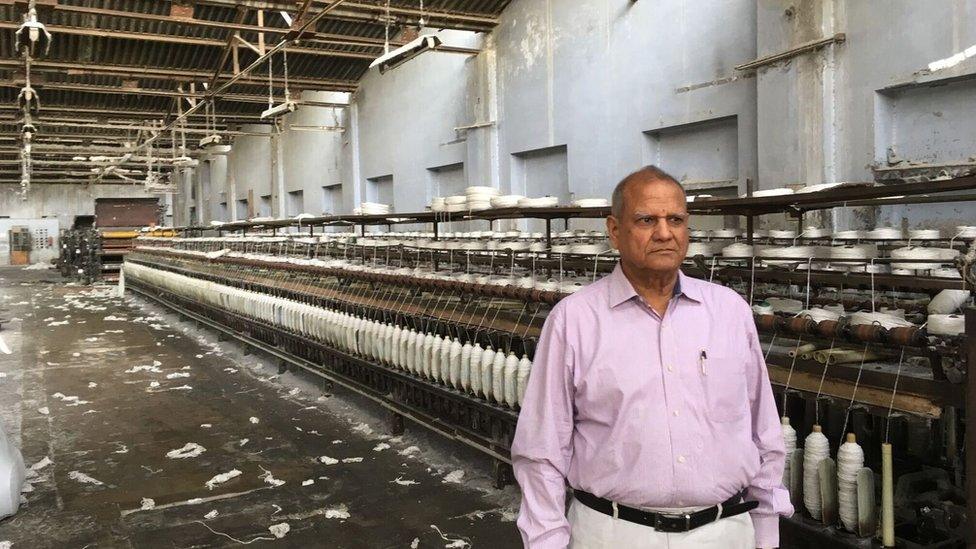

Pawan Garg says the industry has shrunk dramatically

Africa is the biggest consumer for what's made here. Almost all traders visit markets in African countries regularly to find new buyers for their recycled fabric.

There is a local market too - but it's much smaller.

While the cost of importing this textile waste is very low, Mr Kumar is worried that what was once a lucrative business is now getting more expensive.

"Once it reaches India - the custom duties, transportation, storage, electricity and labour costs adds up. Our consumers in Africa want cheap blankets and we are struggling to keep the prices low."

Global Trade

More from the BBC's series taking an international perspective on trade:

The lucrative world of 'the super tutor'

How shops are coping with a weaker pound

The apples that need shading from the sun

How the 'better burger' is taking over the world

What it takes to get Beyonce on a world tour

The country losing out in the breakfast juice battle

The industry has also been affected by increased competition from cheaper man-made fibres such as polyester.

Pawan Garg, the president of trade body the All India Woollen & Shoddy Mills Association, says the industry has already shrunk dramatically as a result.

"There were once more than 400 units here - now there are less than 100 units. It's taken a very bad hit. The industry is not doing well. Every day - a unit is closing or reducing production.

Shilpa Kannan visits the city of Panipat

"Earlier we worked 24/7, now it's hardly a shift a day," he says.

If the industry continues to shrink it won't just be a problem in India, points out Mr Kumar. He suggests the West could help support the industry.

"What we do here is important work. Think about the impact on the environment if we don't use up these huge mountains of waste.

"In India, things never get wasted. We pass on our clothes to those who need them, and even after that we find ways of using the fabric. I can't think of ever throwing a piece of clothing in the dustbin."