Glittering prize: The booming demand for opals

- Published

Global demand for opals is soaring, pushing up prices of the gemstones.

As the 40ft (12m) drill rattles down through the red dirt, miner Craig Stutley makes a statement that sounds a lot like what he said 30 minutes ago.

"This is the hole," says the 45-year-old.

Mr Stutley's mining partner, Richard Saunders, who seems eternally caked in dusty soil, mumbles in agreement.

The two men are standing in the middle of the sun-bleached South Australian outback, hunting for opals, the rare gemstones that can sparkle with a rainbow of different colours.

They sift through the earth that the test drill pulls up, searching for signs of opals that could potentially make them a fortune.

With the largest, best-quality Australian opals worth more than £600,000 thanks to soaring demand from jewellers around the world, there is a vast amount of money to be - potentially - made.

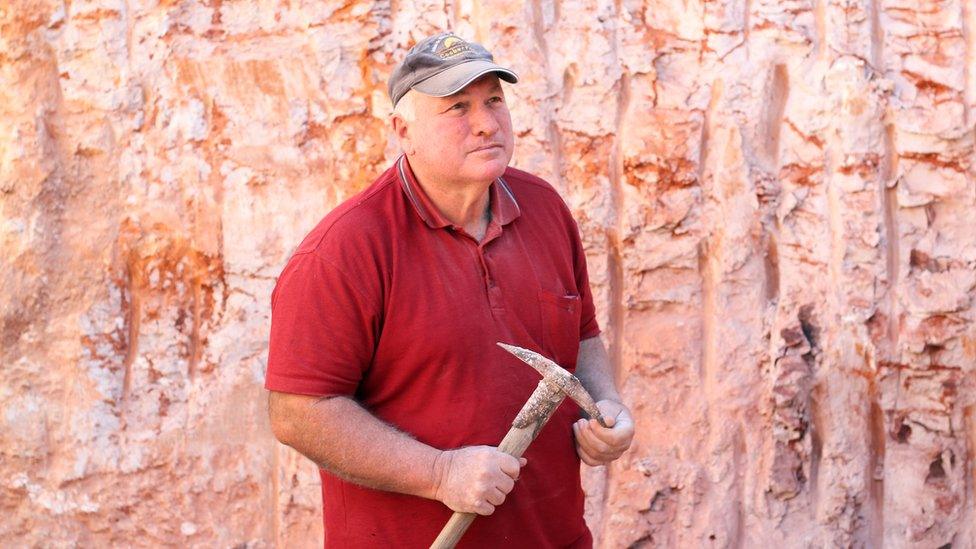

Richard Saunders (pictured) and his friend Craig Stutley are hoping for a big find

The trouble is that opals are so scarce. Even in designated opal fields, you need luck, and months, or even years, of patience to find them.

"Half of it is in your head," says Mr Stutley. "You have to think positive, otherwise you wouldn't come to work."

Mr Stutley and Mr Saunders are mining a patch of land 15 miles north of the South Australian town of Coober Pedy, which is known as "the opal capital of the world".

South Australia supplies 80% of the world's opals, and the industry is centred on Coober Pedy, a town of around 3,500 people located 850 miles (1,368km) north of Adelaide, and 430 miles south of Alice Springs.

At the peak of the opal rush 40 years ago there were thousands of miners based in the town that can see summer temperatures top 47C (117F), but as finds have steadily fallen ever since, today there are just dozens.

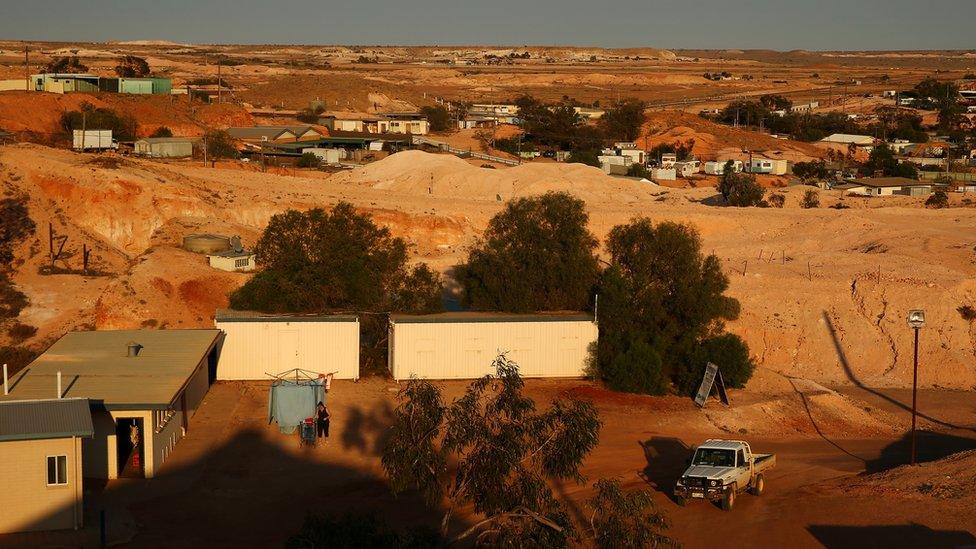

The Shell Patch mining area is a desolate area of rocky ground

There is, however, still considerable amounts of money to be made, with state-wide opal output totalling 15.1m Australian dollars ($11.5m; £9m) last year, according to the South Australian government.

This comes as the global prices of opals have doubled in the past few years, thanks to constant demand from India and China, as well as an opal renaissance in western markets such as the US.

While Mr Stutley and Mr Saunders are still waiting for their big find, they did at least have some recent luck, when in March they won a free lottery to mine a newly reopened opal field.

The pair, along with about 50 other miners, were chosen at random to restart mining in Shell Patch Reserve, an area that had been off limits for 40 years due to its importance to local Aboriginal people. More than 200 people had entered the lottery, and the winners got plots or "claims" of land that measure 100m by 50m (328ft by 164ft).

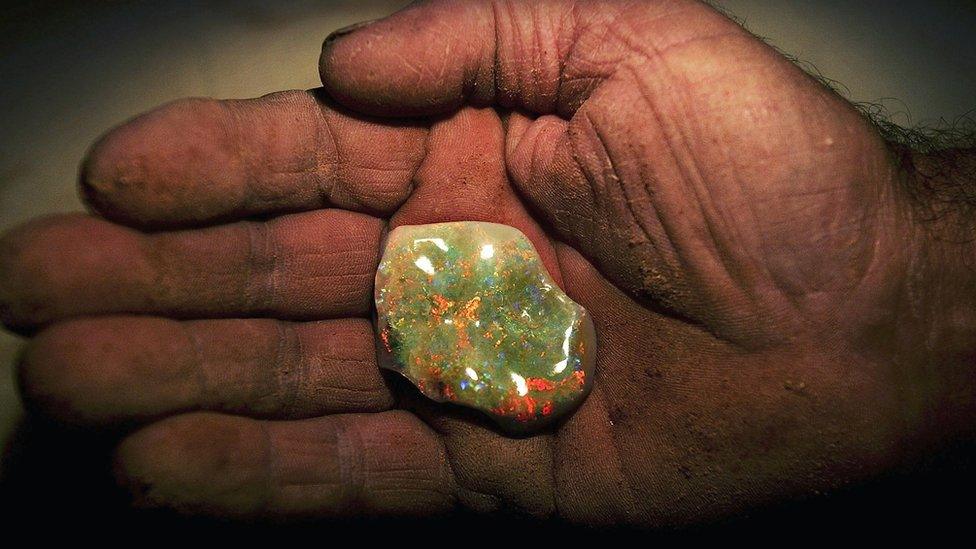

Opals are typically sliced and made into jewellery

John Dunstan, the vice president of Australia's Opal Mining Association, was one of the first to get to work at Shell Patch.

He has already received a small payday after finding a piece (known in the industry as a "parcel") of opal worth about 5,900 Australian dollars.

Rather than tunnelling into the ground, Mr Dunstan is open-cut mining, which involves scraping away a few inches of rock with an excavator, and then periodically investigating for opals.

He hopes that a big find at Shell Patch will attract new entrants into the industry.

John Dunstan wants to see a new generation of opal miners

"There hasn't been a major strike [in Coober Pedy] for quite a few years," says Mr Dunstan.

"We are desperate to find a new opal field and hopefully attract some new opal miners."

He adds that there's a saying in Coober Pedy that often rings true - the moment you find your first opal you catch "opal fever".

Its symptom is a relentless pursuit of opal, which is Australia's national gemstone.

Coober Pedy has a population of just 3,500

For Mr Dunstan that moment happened at age 14 back in 1965 when he found his first opal.

"It's a lifestyle for me," he says. "It's a passion."

Justin Lang, 27, is one of the new miners that Mr Dunstan wants to see. He and his business partner, Daniel Becker, 43, started opal mining five years ago.

More stories from the BBC's Business Brain series looking at quirky or unusual business topics from around the world:

Can you be taught to be more charismatic?

Does selling up mean selling out?

Mr Becker says they approach it as "a hobby that makes you money".

About one week a month they leave the shops where they work in the town of Hahndorf, near Adelaide, and head to Coober Pedy, where they mine several different fields.

Opal miners sieve soil to try to find the gemstones

Mr Lang says: "The possibility of finding millions and millions of dollars is real."

He adds that he is also drawn to opal mining because it favours small operators, unlike the multi-million dollar companies that mine Australia for copper and uranium.

Finding opal is "just too irregular" for big business, says Mr Lang.

For Mr Lang and his fellow miners, it also doesn't hurt that opals are back in vogue, and quite literally in Vogue.

Opal miners say they get "opal fever"

Earlier this year the magazine profiled, external young jewellery designers who are making "opal cool again" after years with a reputation as either an antique that grandma wore, or as tacky jewellery that tourists would buy from Australian airports.

In another boost to opal's comeback, Dior's latest jewellery collection is centred on the gemstone.

"Every opal is completely different," says Emily Amey, a New York-based jewellery designer who sources many of her opals from Australia. "Different colours, different patterns, they are just mystical."

While Ethiopia is now extracting about half the amount of opals that South Australia produces - other nations with sources of opals include Brazil and Peru - Australia is not going to lose its number one crown anytime soon.

Jeweller Emily Amey says that no opal is the same as another

Australian miners such as Mr Dunstan just seemingly need a mixture of blind positivity, patience and luck to find the gemstones.

"There are still millions of dollars here to be found," he says. "You've just got to be digging in the right spot."